Three degrees of separation: alternatives to divorce in early modern England

Reply

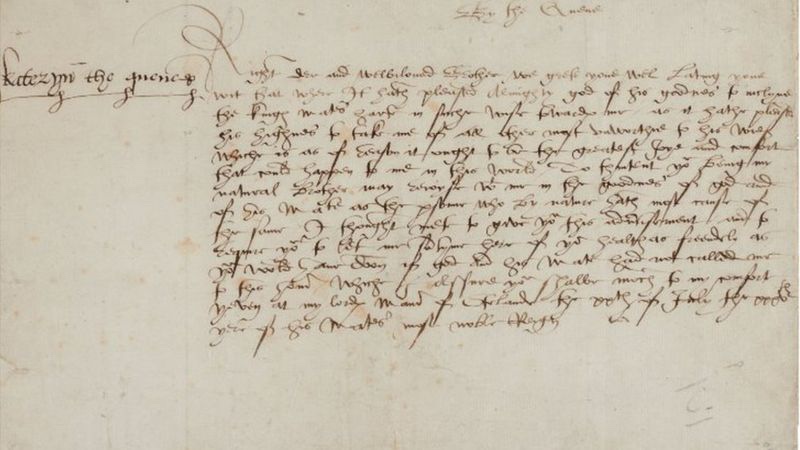

I love how much people dismiss Queen Kateryn Parr. There may be evidence that she WAS supposed to be Regent for Edward VI. See her signature AFTER Henry died.

She was apparently signing as “Kateryn, the quene regente KP”. The theory goes that she was indeed made Regent for her stepson, King Edward VI. Which would make sense with the use of her signature. It is believed that Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, Kateryn’s brother the Marquess of Northampton, her brother-in-law the Earl of Pembroke and the council ousted her and rewrote the will. She would have made a wonderful Queen Regent. She proved she was capable of being Regent while Henry went to war with France. Perhaps she would have lived longer and prevented the succession from being rewritten. She gets credit for the placement of Princesses Mary & Elizabeth back into the line of succession behind their brother in 1545. That succession act seems to have overwritten or they disregarded King Edward’s will and supported the actual heir to the throne, Mary. Mary WAS the rightful heir. Jane was further down the approved line of succession. Why would you accept someone below the status of the actual daughters of King Edward’s father, Henry VIII? Kateryn Parr’s brother and brother in law were again involved in matters of the state and actually pulled off putting Lady Jane Grey on the throne for 9 days! Jane somehow outranked her own mother who was STILL alive and technically would have been the next heiress to the throne after Princesses Mary & Elizabeth. I never understood that. The Protestants feared the Catholic “Bloody Mary” (her nickname was started as Protestant propaganda, the pro Queen Elizabeth movement, lol) would try to return the country to the Pope and Catholicism. Mary was deeply religious. Kateryn Parr and Mary got on despite differences in matters like religion. Parr’s mother, Lady Maud, had served Mary’s own mother, Queen Katherine of Aragon, the first wife and crowned Queen consort to King Henry. The two women were pretty close. The Parrs backed Queen Katherine of Aragon when her lady in waiting became the Kings new obsession. Parr let Mary be and encouraged her every chance she could. One could argue she loved Mary more than Elizabeth. Heck, Kateryn named her only daughter and child, Mary, before the queen passed on 5 September 1548. Don’t think there were any other important Marys. The French Queen, Mary Tudor, had died long before Parr became Queen. Pretty sure it’s not after The Virgin Mary. Protestants aren’t that attached to her, right? I was raised Catholic, so I honestly don’t know. Anyway, Queen Kateryn Parr was VERY important. Read a book. She wasn’t an ex-queen. She remained Queen (consort) of England, Ireland, and France until she died. She was the LAST Tudor Queen Consort as King Edward died young. She was also the FIRST Queen of Ireland. Her funeral was the FIRST Protestant funeral for a Queen. Her mourner was none other than Lady Jane Grey, who would have probably stayed with Kateryn had the queen lived. Having Parr around seemed to pacify things. She knew how to handle tricky and dangerous situations. For Gods sake, she almost lost her head after she spoke with the King. It was overheard by the queens enemy, Bishop Gardiner, who saw an opportunity to “get rid” of Kateryn. I mean why not? He already KILLED TWO WIVES!! Lordy, so Gardiner tried to fuck with the Kings head. Saying shit like “it is a petty thing when a woman should instruct her husband” or some stupid sexist bs! Story goes, Kateryn was warned by an anonymous source who found her death warrant lying on the ground. YEAH RIGHT!! That’s straight up narcissistic abuse, my man!! Why do I feel like Henry set her up to test her loyalty? He was such a theatrical douche bag. No, no love for King Henry here. I have yet to see the film “Firebrand” which follows the reign of Kateryn as queen consort and queen Regente I believe. It’s based off Elizabeth Freemantle’s “Queen’s Gambit”. Anyway, Kateryn talked her way out of being arrested or worse by stroking the Kings ego and basically submitting to him just to fuvking survive. Imagine going through this marriage without psych meds like Benzos. I do believe they dabbled in potions however and she was known to “treat” melancholy with herbs from the gardens. Sudeley Castle where she is buried has a garden full of deadly herbs. Physic gardens. I have photos somewhere…

My page: Queen Catherine Parr

© 2024 Meg McGath. All research and original commentary belong to the author.

Right dear and well-beloved brother, we great you well. Letting you wit that when it hath pleased almighty God of His goodness to incline the King’s majesty in such wise towards me, as it hath pleased his highness to take me of all others, most unworthy, to his wife, which is, as of reason it ought to be, the greatest joy and comfort that could happen to me in this world:

To the intent, you being my natural brother, may rejoice with me in the goodness of God and of his majesty, as the person who by nature hath most cause of the same, I thought meet to give your this advertisement. And to require you to let me sometime hear of your health as friendly as you would have done, if God and his majesty had not called me to this honor: which, I assure you, shall be much to my comfort. Given at my lord’s manor of Oatlands, the twentieth of July, the thirty-fifth year of his majesty’s most noble reign.

Kateryn, the quene

Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondences, editor Janel Mueller. University of Chicago, 2011. pg 46.

Letter signed (“Kateryn the queen”), to her brother William Parr,

ANNOUNCING HER MARRIAGE TO KING HENRY VIII, explaining that “It hath pleased Almighty god of his goodness to incline the Kinges ma[jes]tes harte in suche wise towards me”, celebrating an event which is “the greatest Joye and comfort that could happen to me in this world”, and inviting her brother to “rejoyse with me in the goodness of god and of his Ma[jes]te”, 1 page, oblong folio, Oatlands, 20 July 1543, integral address leaf (“To our right der and entirely beloved Brother the Lord Parre Lord Warden of the Marches…”), docketed, fragile at folds, crude repair to marginal tear, spotting

HENRY VIII’S FINAL QUEEN ANNOUNCES HER MARRIAGE TO THE KING. This remarkable letter was written just days after the marriage between the aging Henry VIII and his final Queen. The wedding ceremony had taken place on 12 July in the Queen’s Closet at Hampton Court Palace, attended by only 18 people. The couple immediately started on the court’s summer progress and this letter was written from the first stop on their journey, Oatlands Palace in Surrey.

Description of Lot from Sotheby’s

The letter is up for auction. I noticed that this is not her handwriting and her signature is not followed by her maiden initials KP. Did the initials come later in her reign as queen?

By Meg Mcgath, 22 March 2023 *be kind and if you find info here…leave breadcrumbs. Thanks!*

Lady Maud Parr, (6 April 1492 – 1 December 1531) was the wife of Sir Thomas Parr of Kendal, Knt. She was the daughter and substantial coheiress of Sir Thomas Green of Greens Norton, Northamptonshire. The Greens had inhabited Greens Norton since the fourteenth century. Green was the last male heir, having had two daughters. Her mother is named as Joan or Jane Fogge. However, I haven’t been able to prove her parentage. According to Linda Porter, Katherine Parr is a great-granddaughter of Sir John Fogge. When asked for a source, Porter said it came from Dr Susan James. In her biography on Katherine, Susan James states, “he [Green] had made an advantageous with the granddaughter of Sir John Fogge, treasurer of the Royal household under Edward IV”. Fogge was married to Alice Haute (or Hawte), a lady and cousin to Edward’s queen, Elizabeth. By her father, Maud descended from King Edward I of England multiple times. Her sister, Anne, would marry Sir Nicholas Vaux (later Baron). Vaux married firstly to Maud’s would be mother-in-law, the widowed Lady Elizabeth Parr, by whom he had three daughters including Lady Katherine Throckmorton, wife to Sir George of Coughton. Her father spent his last days in the Tower and died in 1506 trumped up on charges of treason.

Ten months after the death of her father, the fifteen year old Maud became a ward of Thomas Parr of Kendal (c.1471/1478 (see notes)-1517) a man nearly twice her age. Around 1508, Maud married to Thomas, son of Sir William Parr of Kendal (1434-1483) and Elizabeth FitzHugh (1455/65-1508), later Lady Vaux. At the time, he was thirty seven while she was about sixteen. He would become Sheriff of Northamptonshire, master of the wards and comptroller to King Henry VIII. He would become a Vice chamberlain of Katherine of Aragon’s household. When Princess Mary was christened, he was one of the four men to hold the canopy over her. He would become a coheir to the Barony of FitzHugh in 1512 and received half the lands of his cousin, George, 7th Baron (d.1512). Had he lived, he most likely would have received the actual title as a favored courtier. The barony is still in abeyance.

Maud became a lady to Queen Katherine of Aragon along with Lady Elizabeth Boleyn, mother of the future Queen Anne. It seems as though the Parrs and Boleyns were indeed in the same circle around the king—something rarely noted! Both Thomas Boleyn and Thomas Parr were knighted in 1509 at the coronation of King Henry VIII and Queen Katherine of Aragon.

Maud’s relationship with the Queen was a relationship that went much deeper than “giddy pleasure”. Both knew what it was like to lose a child in stillbirths and in infancy. It was Katherine Parr’s mother, Maud, who shared in the horrible miscarriages and deaths in which Queen Katherine would endure from 1511 to 1518. The two bonded over the issue and became close because of it. Lady Parr became pregnant shortly after her marriage to Sir Thomas Parr. Most people think that Katherine Parr, the future queen and last wife of Henry, was the first to be born to the Parrs; not so. In or about 1509, a boy was born to Maud and Thomas. The happiness of delivering an heir to the Parr family was short lived as the baby died shortly after — no name was ever recorded. It would be another four years before Maud is recorded as becoming pregnant again. In 1512, Maud finally gave birth to a healthy baby girl. She was christened Katherine, after the queen, and speculations are that Queen Katherine was her godmother. In about 1513, Maud would finally give birth to a healthy baby boy who was named William. Then again in 1515, Maud would give birth to another daughter named Anne, possibly after Maud’s sister.

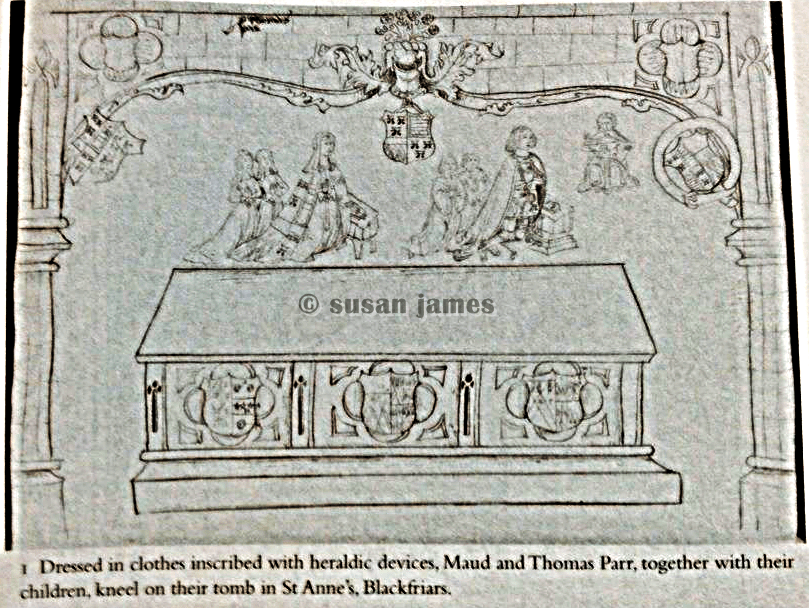

In or about 1517, Maud became pregnant again. It was in autumn of that year that her husband, Sir Thomas, died at his home in Blackfriars of the sweating sickness. Maud was left a young widow at 25, with three small children to provide for. It is believed that the stress from his death caused the baby to be lost or die shortly after birth. No further record of the child is recorded. In a way Maud might have been relieved. He left a will, dated 7 November, for his wife and children leaving dowry’s and his inheritance to his only son, William, but as he died before any of his children were of age, Maud along with Cuthbert Tunstall, their uncle Sir William Parr, and Dr. Melton were made executors. He left £400 apiece as marriage portions for his two daughters. He provided for another son and if the baby was “any more daughters”, he stated “she [Maud] shall marry them at her own cost”. In his will, Parr mentions a signet ring given to him by the King which illustrates how close he was to him. He was buried in St. Anne’s Church, Blackfriars, beneath an elaborate tomb. His tomb read, “Pray for the soul of Sir Thomas Parr, knight of the king’s body, Henry the eigth, master of his wards…and…Sheriff…who deceased the 11th day of November in the 9th year of the reign of our sovereign Lord at London, in the Black Friars..” Maud chose not to remarry for fear of jeopardizing the huge inheritance she held in trust for her children. She carefully supervised the education of her children and studiously arranged their marriages.

In October 1519, Maud was given her own quarters at court. From 7 to 24 June 1520, Maud attended the queen at The Field of the Cloth of Gold, the meeting between King Henry VIII and King Francis I of France. Her sister, Anne, now Lady Vaux, and her husband, Nicholas, along with her other in laws, Lord Parr of Horton and his wife, were also present.

According to this article, which states no sources,

“In 1522, Maud was assessed for a “loan” to the King for the French Wars, of 1,000 marks, a very substantial sum, the same as the amount provided by Lord Clifford. She appears in the various household accounts of Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon as entitled to breakfast at Crown expense and to suits of livery for her servants, as well as lodgings, which were very hard to come by.

In 1523, Maud started writing letters to find a suitable husband for her daughter, Katherine. Henry le Scrope (c.1511-25 March 1525), son and heir to Sir Henry le Scrope, 7th Baron Scrope of Bolton by his wife Mabel Dacre, was a cousin. The negotiations lead to nothing. By 1529, Maud found a match for her daughter in Sir Edward Borough, son of Sir Thomas.

When regulations for the Royal household were drawn up at Eltham, in 1526, Lady Parr, Lady Willoughby and Jane, Lady Guildford were assigned lodgings on “the queen’s side” of the palace. If an emergency arose, yeoman were sent with letters from the queen “warning the ladies to come to the court”. Maud was still listed, along with only five other ladies, which included the King’s sister, as having the privilege of having permanent suites in 1526. Maud was friendly with the King as well—her husband had been a favored courtier—and gifted him a coat of Kendal cloth in 1530. She was gifted miniatures of the King and Queen from the Queen herself.

In the summer of 1530, Maud visited her daughter, now Lady Katherine Borough, in Lincolnshire. She stayed at her own manor in Maltby, which was eighteen miles from Old Gainsborough Hall. It is thought that her presence there influenced Sir Thomas Borough to give his son, Edward, a property in Kirton-in-Lindsey. This gave Katherine an opportunity to manage a household of her own.

Maud continued her position at court as one of Katherine of Aragon’s principal ladies and stayed close to the Queen even when her relationship with the king started to decline. Henry’s infatuation with Anne Boleyn, one of the Queen’s ladies, became apparent and inevitably the ladies began to take sides. In these times, Queen Katherine never lost the loyalty and affection of women like Maud Parr, Gertrude Courtenay, and Elizabeth Boleyn, who had been with the Queen since the first years of her reign. At the time of her death, Maud was still attending Queen Katherine.

Maud died on 1 December 1531 at age thirty nine and is buried in St. Ann’s Church, Blackfriars Church, London, England beside her husband.

“My body to be buried in the church of the Blackfriars, London. Whereas I have indebted myself for the preferment of my son and heir, William Parr, as well to the king for the marriage of my said son. As to my lord of Essex for the marriage of my lady Bourchier, daughter and heir apparent to the said Earl. Anne, my daughter, Sir William Parr, Knt., my brother, Katherine Borough, my daughter, Thomas Pickering, Esq., my cousin and steward of my house.”

In her will, dated 20 May 1529, Maud designated that she wanted to be buried Blackfriars where her husband lies if she dies in London, or within twenty miles. Otherwise, she could be buried where her executors think most convenient. Maud left her daughter, Katherine, a jeweled cipher pendant in the shape of an ‘M’. Maud also left Katherine a cross of diamonds with a pendant pearl, a cache of loose pearls, and, ironically, a jeweled portrait of Henry VIII. To her daughter, Anne, she left 400 marks in plate and a third share of her jewels. The whole fortune, Lady Parr had directed, was to be securely chested up ‘in coffers locked with divers locks, whereof every one of them my executors and my … daughter Anne to have every of them a key’. ‘And there’, Lady Parr’s will continued, ‘it to remain till it ought to be delivered unto her’ on her marriage. She also provided 400 marks for the founding of schools and “the marrying of maidens and especial my poor kinswomen”. Cuthbert Tunstall, who was the principal executor of Maud’s will, she left to “my goode Lorde Cuthberd Tunstall, Bisshop of London…a ring with a ruby”. Tunstall had been an executor of her late husband’s will as well. An illegitimate son of Sir Thomas of Thurland Castle, he was a great-nephew of Alice Tunstall, paternal grandmother to Sir Thomas Parr. To her daughter-in-law, Anne, she left substantial amounts of jewelry, “to my lady Bourchier when she lieth with my son” as a bribe to get the marriage consummated. Maud also left a bracelet set with red jacinth to her son, William. She begs him “to wear it for my sake”. Maud was also stated in her will, “I have endetted myself in divers summes for the preferment of my sonne and heire William Parr as well”. For her cousin, Alice Cruse, and Thomas Parr’s niece, Elizabeth Woodhull or Odell, Maud left “at the lest oon hundrythe li”. She wills her “apparrell [to] be made in vestments and other ornaments of the churche” for distribution to three different parish churches which lay close to lands that she controlled. She bequeathed money to the Friars of Northampton. For centuries, historians have confused the first husband of her daughter, Katherine, with his elder grandfather, Edward, the 2nd Baron Borough or Burgh of Gainsborough (d.August 1528). He was declared insane and was never called to Parliament as the 2nd Baron Borough. Some sources mistakenly state she was just a child at the time of her wedding in 1526. Katherine’s actual husband, Sir Edward Borough (d.1533), was the eldest son and heir of the 2nd Baron’s eldest son and heir, Sir Thomas Borough, who would become the 1st Baron Borough under a new writ in December 1529. Katherine and Edward were married in 1529. At the time, Thomas Borough was still only a knight. Maud mentions in her will, Sir Thomas, father of the younger Edward, saying ‘I am indebted to Sir Thomas Borough, knight, for the marriage of my daughter‘. Edward was the eldest son and heir to his father, Sir Thomas, Baron Borough. He would die in 1533. Maud’s will was proved 14 December 1531.

Maud and Thomas had three children to survive infancy.

Katherine or “Kateryn” (1512-1548), later Queen of England and Ireland, would marry four times. In 1529, Katherine married Sir Edward Borough. He died in 1533. In 1534, Katherine became “Lady Latimer” as the wife to a cousin of the family, Sir John Neville, 3rd Baron Latimer (of Snape Castle). He was dead by March 1543. A few months later, on 12 July, Katherine married King Henry VIII at Hampton Court Palace. The king died in January 1547. In May of that year, Katherine secretly wed Sir Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour (d.1549) of Sudeley Castle, a previous suitor from 1543. Their love letters still survive. By Seymour, Katherine had a daughter, Mary. Katherine died 5 September 1548. Seymour would be executed 20 March 1549 for countless treasonous acts against the crown (his nephew was King Edward VI).

William (1514-1571) married on 9 February 1527, at the chapel of the manor of Stanstead in Essex, to Anne Bourchier, suo jure 7th Baroness Bourchier (d. 26 January 1571), only child and heiress of Henry Bourchier, 2nd Earl of Essex (d.1540). In 1541, she eloped from him, stating that “she would live as she lusted”. Susan James states the next year, Parr secured a legal separation. James also states that on 13 March 1543, a bill was passed in Parliament condemning Anne’s adulterous behavior and declaring any children bastards. Wikipedia states “On 17 April 1543 their marriage was annulled by an Act of Parliament and any of her children “born during esposels between Lord and Lady Parr””(there were none) were declared bastards. The source is G. E. Cokayne, ”The Complete Peerage”, n.s., Vol.IX, p.672, note (b). I have not been able to access The Complete Peerage to confirm. On 31 March 1551, a private bill was passed in Parliament annulling Parr’s marriage to Anne. She predeceased Parr by a few months. William married Elisabeth Brooke (1526-1565), a daughter of George Brooke, 9th Baron Cobham of Cobham Hall in Kent, by his wife Anne Bray. A commission ruled in favour of his divorce from Anne shortly after he married Elizabeth Brooke in 1547, but Somerset punished Parr for his marriage by removing him from the Privy Council and ordering him to leave Elizabeth. The divorce was finally granted in 1551, and his marriage to Elizabeth was made legal. On 31 Mar 1552, a bill passed in Parliament declaring the marriage of Anne Bourchier and Parr null and void. Their marriage was declared invalid in 1553 under Queen Mary and valid again in 1558 under Queen Elizabeth who adored William. Each change of monarch, and religion, changed Elizabeth’s status. She died in 1565. William married Helena Snakenborg in May 1571 in Elizabeth’s presence in the queen’s closet at Whitehall Palace with pomp and circumstance. Parr would die 28 October 1571.

Anne (1515-1552) who married Sir William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke in 1538. They had three children: Henry, Edward, and Anne. They are ancestors to the current Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery, Earl of Carnarvon, Earl of Powis, Marquess of Abergavenny, and other nobility.

Notes

Porter, James, and Mueller state Thomas Parr was born in 1478. However, in James’s biography of Katherine, she states he was 37 at the time of his marriage to Maud Green in 1508. So that would be about 1471, right?

References

Susan James. “Catherine Parr: Henry VIII’s Last Love”, 2010. Google eBook (preview)

Susan James. Women’s Voices in Tudor Wills, 1485–1603: Authority, Influence and Material Culture, 2016. Google eBook (preview)

Meg McGath. “Childbearing: Queen Katherine of Aragon and Lady Maud Parr”, 2012.

Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondence, ed. Janel Mueller, 2011. Google eBook (preview)

Sir Nicholas Nicolas. Testamenta Vetusta: being illustrations from wills, of manners, customs, … as well as of the descents and possessions of many distinguished families. From the Reign of Henry II. to the accession of Queen Elizabeth, Volume 2, 1826. Google eBook

Elizabeth Norton. “Catherine Parr

Wife, Widow, Mother, Survivor, the Story of the Last Queen of Henry VIII”, 2010. Google eBook (preview)

Linda Porter. Katherine the Queen: The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin Publishing, 2010)

Douglas Richardson. Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, 2nd Edition, 2011. Google eBook (preview)

Gareth Russell. Young and Damned and Fair: The Life of Catherine Howard, Fifth Wife of King Henry VIII, 2017. Pg 215. Google eBook (preview)

Agnes Strickland. Lives of the Queens of England, from the Norman Conquest With Anecdotes of Their Courts, Volumes 4-5, 1860. Pg 16. Google eBook

Tudor and Stuart Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty, ed. Aidan Norrie, Carolyn Harris, Danna R. Messer, Elena Woodacre, J. L. Laynesmith, 2022. Google eBook (preview)

The Antiquary: A Magazine Devoted to the Study of the Past, volume 24, 1891. Google eBook

The Reliquary, Volume 21, 1881. Google eBook

Sir William Parr, 1st Baron Parr of Horton (c. 1483 – 10 September 1546) was the son of Sir William Parr of Kendal and his wife Elizabeth Fitzhugh. His mother was a niece to Warwick, the Kingmaker and thus a cousin of Anne Neville, Duchess of Gloucester and Queen of England as the wife of Richard III. Lady Elizabeth and her mother, Lady Alice FitzHugh, rode in the coronation train for Anne when she became queen and it is believed they stayed on as ladies to the queen. Elizabeth had been in the household since Anne became Duchess.

Parr’s siblings included an elder brother, Sir Thomas Parr of Kendal (d.1517), who was father to the future queen of England, the Marquess of Northampton, and the Countess of Pembroke. Their sister Anne married Thomas Cheney (or Chenye) and was mother to Lady Elizabeth Vaux, wife of the 2nd Baron Vaux of Harrowden. The father of the 2nd Baron was Nicholas Vaux, 1st Baron. His first wife was the widowed Lady Elizabeth Parr, mother to Thomas, William, and Anne. By Elizabeth, Nicholas had 3 daughters, Lady Katherine Throckmorton, Lady Alice Sapcote, and Lady Anne le Strange.

William Parr was a military man who fought in France, where he was knighted by King Henry VIII at Tournai Cathedral, and Scotland. Parr seemed to be uncomfortable in court circles and insecure in securing relationships. None the less he accompanied the King at the ‘Field of the Cloth of Gold’ in France. Like his brother, Sir Thomas Parr, William flourished under Sir Nicholas Vaux.

William was a family man. After the death of his brother, Sir Thomas Parr, William’s sister-in-law Maud, widowed at age 25, called upon him to help in financial matters and to manage her estates in North England while she was busy in the south securing a future for her three children. William had been named one of the executors of his brother’s will. Along with Cuthbert Tunstall, a kinsman of the Parrs, Parr provided the kind of protection and father figure which was missing in the lives of Maud’s children. William’s children were educated along side Maud’s children.

Although William was en-adapt at handling his financial matters, he was ironically appointed the office of Chamberlain in the separate household of Henry FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Richmond and Somerset, the acknowledged illegitimate son of King Henry VIII and Elizabeth Blount, based at Sheriff Hutton Castle in Yorkshire. It was William who found a spot for his nephew, William Parr, later Earl of Essex, in the Duke’s household where he would be educated by the very best tutors and mixed with the sons of other prominent families. Though thought to be a wonderful environment for Parr and his nephew to flourish in, the household was not a great passport to success as Parr hoped for. Henry VIII was very fond of his illegitimate son, but had no intention of naming him his heir. It has been claimed that Parr and his sister-in-law, Maud Parr, coached William to make sure that he ingratiated himself with the Duke, in case the Duke became heir to the throne but there is no factual evidence to support this claim.

Although Parr was named Chamberlain of the Duke’s household, the household was actually controlled by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey in London. This control by Wolsey diminished any opportunity of Parr gaining financial benefit or wider influence. Along with the limited possibilities came other daily frustrations as the Duke’s tutors and the household officers under Parr disagreed on the balance of recreation and study. Parr was a countryman who thought it perfectly normal for boys to prefer hunting and sports to the boring rhetoric of learning Latin and Greek. As the Duke’s behavior became more unruly Parr and his colleagues found it quite amusing. The Duke’s tutor, John Palsgrave, who had only been employed six months, would not tolerate being undermined and decided to resign. Such was the household in which Parr presided over. Parr was suspicious of schoolmaster priests and anyone of lesser birth, even though he was not considered a nobleman at the time. The experience did not further the Parr family. If Sir William had paid more attention to his duties and responsibilities he may have reaped some sort of advancement; thus when the overmanned and over budgeted household was dissolved in the summer of 1529, Parr found himself embittered by his failure to find any personal advancement or profit from the whole ordeal.

Despite his failed attempts at achieving personal gain from the household of the Duke, Sir William made up for it during the Pilgrimage of Grace during 1536. William showed impeccable loyalty to the Crown during the rebellion. He had been in Lincolnshire along with Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk and supervised the executions at Louth and Horncastle. William tried to ingratiate himself with Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk and Thomas Cromwell, 1st Earl of Essex. Parr’s presence at the execution in Hull of Sir Robert Constable prompted Cromwell to share in confidence a correspondence in which he received from the Duke of Norfolk on William’s “goodness” which “never proved the like in any friend before.”

Sir William was Sheriff of Northamptonshire in 1518 and 1522. He was also Esquire to the Body to Henry VII and Henry VIII. In addition to this, he was a third cousin to King Henry VIII through his mother. William was appointed Chamberlain to his niece Katherine Parr and when she became Queen regent during Henry’s time in France, Catherine appointed William part of her council. Although he was too ill to attend meetings, the appointment shows her confidence in her uncle.

Parr was knighted by King Henry VIII on Christmas Day, 1513. He was made a peer of the realm as 1st Baron Parr of Horton on 23 December 1543. Upon his death in 1546, with no male heirs, the barony became extinct.

He married Mary Salisbury, the daughter and co-heir of Sir William Salisbury; who brought as her dowry the manor of Horton. It was a happy marriage which produced four daughters who survived infancy:

* Maud (Magdalen) Parr, who married Sir Ralph Lane of Orlingbury. One of their children was Sir Ralph Lane, the explorer. Maud grew up with her cousin Katherine Parr, who would later become the last queen of Henry VIII. Maud would become a lifelong friend and confidante of the queen.

* Anne Parr, who married Sir John Digby.

* Elizabeth Parr, who married Sir Nicholas Woodhall.

* Mary Parr, who married Sir Thomas Tresham I.

He is buried at Horton, Northamptonshire where the family estate was.

Lady Maud Lane and Lady Mary Tresham are ancestors to the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Sussex through their late mother, the Princess of Wales.

Ever wonder why SOME sources mix up Anne and Mary?

References

‘Parishes: Horton’, A History of the County of Northampton: Volume 4 (1937), pp. 259-262. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=66363&strquery=SirWilliamParr Date accessed: 19 October 2010.

Burke, A general and heraldic dictionary of the peerages of England, Ireland, and Scotland, extinct, dormant, and in abeyance, pg. 411

Porter, Linda. Katherine, the Queen: The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII. Macmillan, 2010.

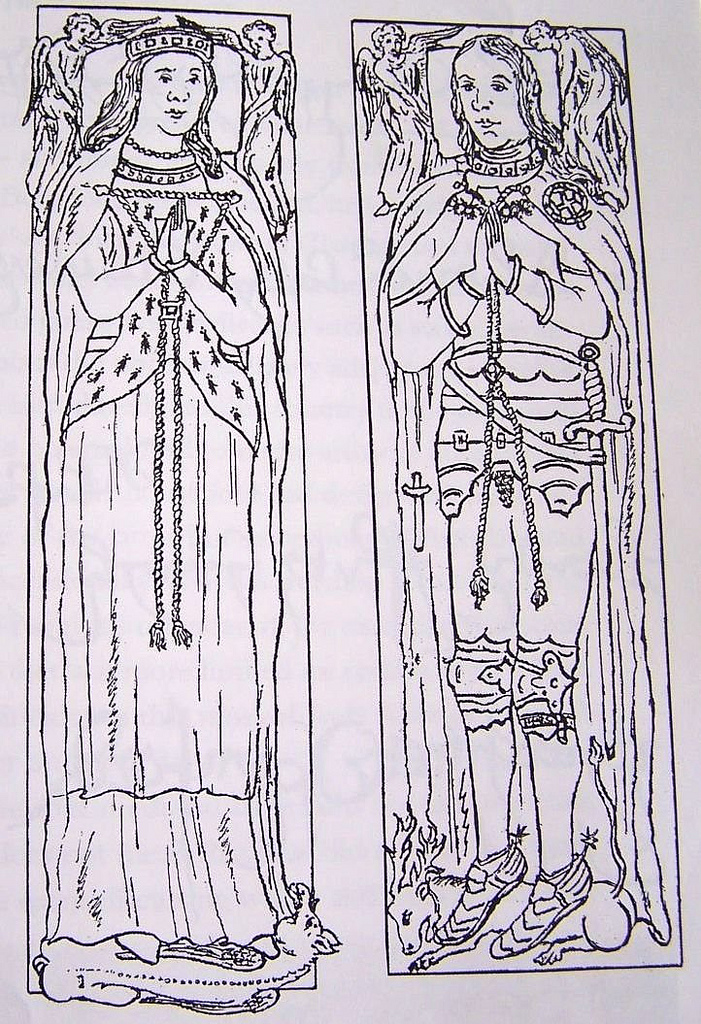

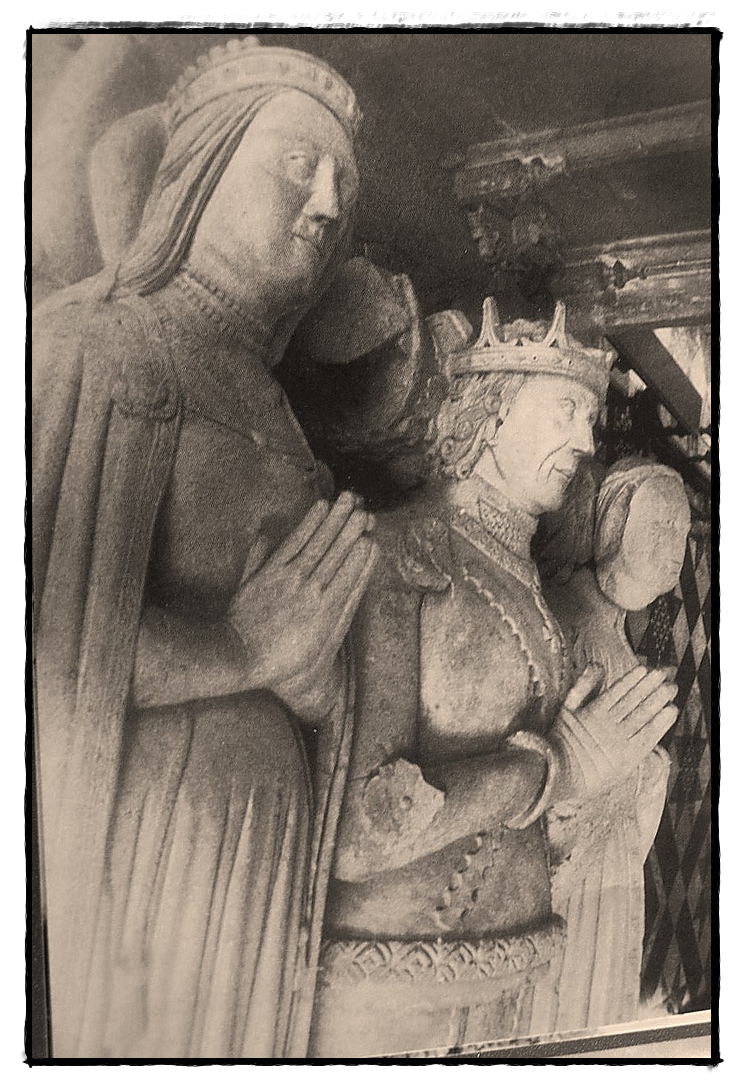

Redrawn effigy of John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford and Lady Margaret before it was destroyed; original illustration was by Daniel King, Colne Priory Church, destroyed c. 1730.

Redrawn effigy of John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford and Lady Margaret before it was destroyed; original illustration was by Daniel King, Colne Priory Church, destroyed c. 1730.Margaret Neville, Countess of Oxford (c.1443[1]-after 20 November 1506/1506[1][2]) was the daughter of Sir Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury and Lady Alice [Montague], suo jure 5th Countess of Salisbury [in her own right]. Margaret was born in her mother’s principal manor in Wessex.[1] She was the last of six daughters and ten children.[1] Margaret’s godmother and namesake may have been after Margaret Beauchamp (1404 – 14 June 1468), eldest daughter of Sir Richard Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick and his first wife Elizabeth Berkeley. Beauchamp was wife to John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury [a brother to Mary Talbot, Lady Greene, the maternal 3x great-grandmother to Queen Katherine Parr and thus a 4x great-uncle]. Margaret Talbots’s sister, Anne, suo jure 16th Countess of Warwick would marry Margaret Neville’s brother, Richard, and he would inherit Anne’s title through marriage making him the 16th Earl of Warwick.

The Neville family was one of the oldest and most powerful families of the North. They had a long standing tradition of military service and a reputation for seeking power at the cost of the loyalty to the crown as was demonstrated by her brother, the Earl of Warwick.[5] Warwick was the wealthiest and most powerful English peer of his age, with political connections that went beyond the country’s borders. One of the main protagonists in the Wars of the Roses, he was instrumental in the deposition of two kings, a fact which later earned him his epithet of “Kingmaker”.

By her paternal grandmother, Lady Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland, Margaret was the great-great-granddaughter of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. Lady Joan Beaufort was the legitimized daughter of Prince John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and Aquitaine, and his mistress, later wife, Katherine Roët Swynford. As such, Margaret was a great-niece of the Lancastrian King Henry IV. Margaret’s paternal grandfather was Sir Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland, the second husband of Lady Joan. One of their daughters (Margaret’s aunt), Lady Cecily, became Duchess of York and mother to the York kings, Edward IV and Richard III. Margaret’s mother, Lady Salisbury, was the only child and sole heiress of Sir Thomas Montacute, 4th Earl of Salisbury by his first wife Eleanor Holland [both descendants of King Edward I]. Margaret’s grandmother, Lady Eleanor, was the granddaughter of Princess Joan of Kent, another suo jure Countess (of Kent) and Princess of Wales. Princess Joan was of course the mother of the ill-fated King Richard II making Eleanor Holland his niece. Princess Joan herself was the daughter of Prince Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent; son of Edward I by his second wife, Marguerite of France.

Margaret married to John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford, the second son of John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford, and Elizabeth Howard. Oxford was one of the principal Lancastrian commanders during the English Wars of the Roses. Margaret was the last of the sisters to marry. It was her brother, Warwick, who secured the marriage between Margaret and Oxford.[3] Margaret had 1000 marks to offer as a dowry which had been settled upon her in her father’s will in 1460. The financial gain for Oxford was important, but with Margaret he gained a whole family of political advantage; as Margaret was the sister of Warwick. Oxford’s family had been on the Lancastrian side. His father had been executed after trying to replace Edward IV with Henry VI.

At the battle of Bosworth and Stoke, Oxford is recorded as fighting beside the Stanleys’ (husband and son of Oxford’s sister-in-law, Eleanor Neville) on behalf of the House of Lancaster.

As for the wives of rebels, Richard III did indeed give the Countess of Oxford, Margaret Neville, £100, but this was a continuation of a grant from Edward IV, who is not given any particular credit for generosity. In any case, as David Baldwin notes, Richard had been given the Earl of Oxford’s estates following the Battle of Barnet and could presumably afford to part with £100. Back in the 1470′s, the young Richard had bullied Margaret Neville’s mother-in-law, Elizabeth de Vere, the dowager Countess of Oxford, into giving him her own estates for an inadequate consideration, but this inglorious episode doesn’t find its way into Kendall’s biography.

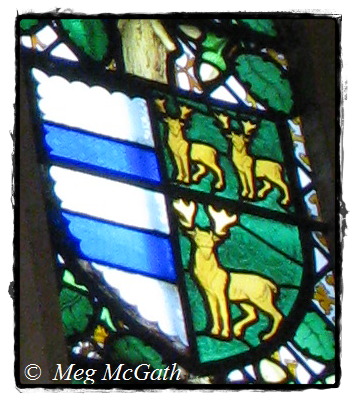

Pembroke family of Wilton. Wilton Church. Left panel shows the 1st Earl of Pembroke with his two sons, Henry (future 2nd Earl of Pembroke) and Sir Edward of Powis.

Sir Edward Herbert of Powis Castle (Jun 1544-23 March 1595) was the second child and son of Sir William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke (10th creation) and his first wife, Lady Anne (Parr). His siblings were Lord Henry Herbert (later 2nd Earl of Pembroke) and Lady Anne Talbot, wife of Lord Francis Talbot. Through his mother, Herbert was a nephew to Queen Katherine Parr and the 1st Marquess of Northampton, William Parr. Upon the death of his aunt, Queen Katherine, his mother became the sole heiress to her brother the Marquess of Northampton.

Herbert was a member of the Herbert family, a Welsh noble family who descended from Sir William ap Thomas of Raglan Castle. His father, Sir William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke of the second creation (within the Herbert family) was the grandson of the first creation also named William (1423-1469). From birth, Edward Herbert had the backing of his family’s powerful clan. It also didn’t hurt that his father, the Earl of Pembroke, would become a large influence at court. Due to his mother’s affiliation to Henry VIII’s last queen, Katherine Parr, Herbert’s father owed some of his advancement to Edward’s mother — Anne. Lady Pembroke (at the time Lady Anne Herbert) was sister to Queen Katherine, the last queen consort to King Henry VIII. In the reign of Henry VIII’s children, especially Edward VI, Pembroke became a guardian to the young king and was part of the court circle of men around the boy. Pembroke tried to advance his standing by marrying his son to a granddaughter of Princess Mary Tudor (Henry VIII’s younger sister and designated heirs to the throne after his immediate children), Lady Katherine Grey. The marriage was to bring the family close to the crown upon the attempt to put Grey’s sister, Lady Jane, on the throne as Queen. When Lady Jane was “deposed,” Pembroke tried to distant himself from the “traitors” which included his brother-in-law, Northampton. Pembroke had the marriage between his son and Lady Katherine annulled and tried to gain favour with the Catholic queen Mary Tudor. The plan worked and his family was spared. Pembroke would also contribute heavily to the reign of Elizabeth I.Lord Pembroke’s marriage to the queen’s sister advanced the family and Anne gave legitimacy to the Herbert family. Lady Pembroke’s descendants also had the luxury of becoming the heirs of the Parr inheritance once Lady Pembroke’s brother, William, 1st Marquess of Northampton died in 1571 without issue. Although the title of Marquess of Northampton and Earl of Essex were forfeit, the children inherited other “titles”, manors, lands, etc.

HANWORTH, a village and a parish in Staines district, Middlesex. Ordnance Survey First Series, Sheet 8.

In June 1544, the Queen lent her sister Lady Herbert her manor, Hanworth for the lying-in for her second child. It was there that Anne Herbert gave birth to her second son, Edward (his elder brother was named Henry, was this a coincidence?). The Queen sent regular messengers to Hanworth to inquire on the health of her sister. For the christening, the queen provided a large delegation (five yeo-men, two grooms, and Henry Webbe) from her household to attend. Letters continued well into July between the two sisters while Lady Herbert remained at Hanworth. After the birth, Lady Herbert visited Lady Hertford (Anne Stanhope), who had also just given birth, at Syon House near Richmond.[1]

In August 1544, the queen paid for a barge to bring her sister Lady Herbert by river from Syon House (home to the Hertford’s) to Westminster. The queen’s involvement in the birth and christening of her nephew would eventually lead her to take him in as part of her household after the death of King Henry.[1]

After King Henry VIII’s death in January 1547, when the queen dowager’s household was at Chelsea, both Lady Herbert and her son Edward were part of the household there. The Dowager queen, as always, was keen to have her family close to her. After having no children of her own by her previous three husbands and no role in the new government, the queen probably didn’t mind having her toddler nephew around. While Lady Herbert attended her sister, her husband Lord Herbert was appointed as one of the guardians to the new king, Edward VI. Lord Herbert became part of the circle around the new king which included his brother-in-law, the Marquess of Northampton.[1]

Hendon Church, Middlesex. London, England; June 1, 1815 (published). John Preston Neale, born 1766 – died 1847 (artist); Bonner, Thomas, born 1735 – died 1816 (engraver) Engraving. Given by Dr. G. B. Gardner. V&A Online Collections.

At the age of his majority, Herbert returned for the family borough and never sat for Parliament again. On the death of his father in 1569, Herbert inherited the manor of Hendon, Middlesex. He also inherited his mother’s lands in Northampton and Westmorland (the Parr inheritance).

Probably the most important event in his life was the purchase of Powis Castle in Wales (at the time it was called “Poole Castell”).[2] Sir Edward Herbert bought the lordship and castle in 1587 from Edward Grey, a feudal Lord of Powis.[3] Edward Grey was the illegitimate child of the last Lord Powis and Jane Orwell; therefore his father’s estates, which he inherited, came with limitations within Lord Powis’s will.[4] One of those limitations was the obvious title, Baron Powis, which would be bestowed on Herbert’s son, William Herbert, in the reign of James I. The castle Sir Edward took over was probably in serious need of repair and modernisation, and he undertook extensive work between 1587 and 1595, of which only the long gallery survives (completed in 1593).[5]

Herbert’s interests were mostly in Montgomeryshire and he had little to do with public life (most likely by choice). He was knighted in 1574. In 1590, his brother the 2nd Earl of Pembroke put him forward for a membership in the council of the marches. Herbert appears to have been of the Catholic faith and that may also explain his non-involvement in Parliament and at the court of Elizabeth I. Herbert’s wife however was Catholic and it was most likely to her influence that he converted. Lord and Lady Herbert’s names appeared on a list of Catholics drawn up between 1574 and 1577; his wife’s name would appear again in 1582. In 1580, Henry Sydney (brother to his sister-in-law Lady Pembroke), was to arrest recusants and did institute proceedings against them in Montgomeryshire. The Herbert’s were left to be until June 1594 when Lady Herbert and her five children, all under age, were presented for recusancy, not having attended Church services (Protestant) at the parish church in Welshpool for twelve months.

Women were very important to the recusant cause in Wales, as in England. Often a wife stayed at home while her husband kept up appearances by attending Anglican services. Some people outwardly conformed to avoid stiff fines, but secretly remained Catholics.

In 1581, it was made treason to convert to Catholicism, or try to convert someone else to it; further measures followed, and the penalty for being caught was often death. But some Catholics risked their lives all the same. The Jesuit order provided many missionary priests, some raised in Wales but trained on the continent. It was a perilous life, and some Welsh homes still have priest holes, where these men hid from the authorities. A number of Welsh Catholics (mostly priests) were executed in the 16th and 17th centuries.[6]

In 1570, Herbert married Mary Stanley, daughter and heir of Sir Thomas Stanley of Standon, Herts. and London. They had four sons and eight daughters.[7] Their children included the eldest son and heir Sir William Herbert, 1st Baron Powis; George, who died unmarried; Sir John Herbert, Knt, who died without issue; Edward, who died a bachelor; Elizabeth died young; Joyce; Frances; Jane; Mary; Winifred; and two more daughters named Anne and Katherine (most likely named after Herbert’s mother and aunt, the queen).[8][9]

Herbert died on 23 March 1595 and was buried in Welshpool Church, Montgomeryshire, where a monument is erected in his memory on the North side of the Chancel. The Herbert memorial consists of two figures in black marble kneeling. In the middle is an inscription in letters of gold, in roman capitols.[9]

Here lyeth the Bodyes of the Right Worshipful Sir Edward Herbert, Knight, second Son to the Right Honourable Sir William Herbert, Knt. Earl of Pembroke, Lord Cardiffe and Knight of the most Noble Order of the Garter, and of Anne his Wife, Sister and sole Heire to Sir William Parr, Kt. Lord Parr of Kirbeby, Kendall, Marmion, FitzHugh, St. Quintin, Earl of Essex, Marquis of Northampton, and Knt. of the most Noble Order of the Garter. Which Sir Edward Herbert married Mary Daughter and sole Heire to Thomas Stanley of Standen, in the County of Hertford, Esq; Master of the Mint, A.D. 1570, youngest Son of Thomas Stanley of Dalgarthe, in the County of Cumberland, Esq. Which Sir Edward Herbert and Dame Mary his Wife had Issue iv Sonnes and viii Daughters, viz.

William Herbert, Esq; his eldest Sonne and Heire, who married Lady Eleanor, second Daughter to Henry late Earl of Northumberland, George Herbert, 2d Son, John Herbert, 3d Son, and Edward Herbert, 4th Son : Elizabeth, first Daughter died young, Anne 2d Daughter, Joyce 3d Daughter, Frances 4th Daughter, Katharine 5th Daughter, Jane 6, Mary 7, and Winifred 8th Daughter. Which Sir Edward died 23 Day of March DMDLXXXXIV and this Monument was made at the Charge of the sayd Lady Herbert 23 October 1595.[9]

Letters of administration were issued to his widow in April 1595.[7]

Books of Hours belonging to Lady Eleanor Powis, wife to Sir William, 1st Baron Powis. Lady Eleanor used her Book of Hours to remind her of important anniversaries writing these dates against the Feast Days of the Catholic Calendar at the front of her book. She includes the birthdays of herself, her husband William, and her children. © National Trust Collections

Sources

Lady Anne Herbert [Parr], Countess of Pembroke died at Baynard’s Castle on 20 February 1552; at the age of thirty-six. Lady Pembroke had out-lived her sister, the Dowager Queen Katherine (d. 5 September 1548), who had also died in the year of her thirty-sixth birthday (Katherine was born in 1512, no official date is recorded). Unlike her sister and brother, the Marquess of Northampton, Lady Pembroke left two sons and a daughter to continue her legacy. Lady Pembroke was buried with huge pomp in Old St. Paul’s Cathedral in London next to her ancestor Prince John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster [and his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster] on 28 February 1552.

On the 28th February was buried the noble countess of Pembroke, sister to the late Queen Katharine, wife of King Henry VIII. She died at Baynard’s Castle and was so carried into Paul’s. There were a hundred poor men and women who had mantle frieze gowns, then came the heralds; after this the corpse, and about her, eight banner rolls of arms. Then came the mourners both lords and knights and gentlemen, also the lady and gentlewomen mourners to the number of two hundred. After these were two hundred of her own and other servants in coats. She was buried by the tomb of the Duke of Lancaster. Afterwards her banners were set up over her and her arms set on divers pillars. (Diary of Henry Machin citizen of London Camden Soc vol 42)

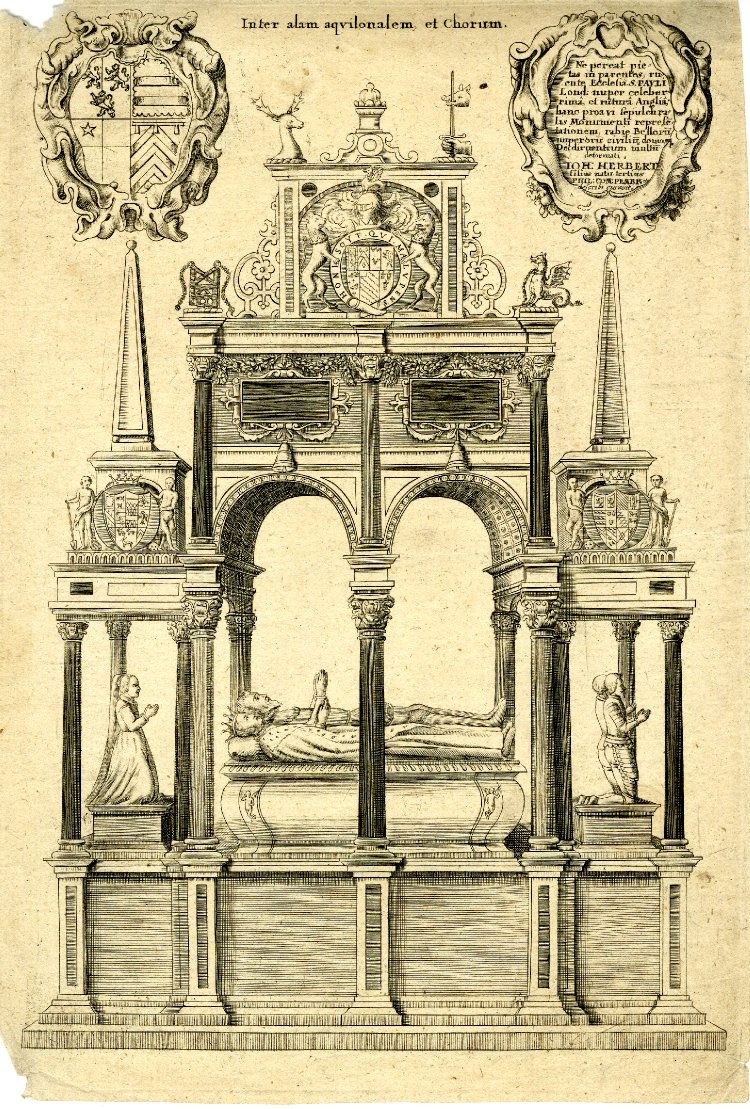

Tomb of William, Earl of Pembroke, in St Paul’s; the tomb on a tall base on which lie a man and wife, in ermine robes, heads to left; eleven columns support a double arch above and obelisk topped extensions at the sides; two cartouches at top, to the left with coat of arms and to the right with dedication by ‘Ioh Herbert’; illustration to William Dugdale’s ‘History of St Paul’s’ (London, 1658 and 1716)

The tomb is located between the choir and the North aisle. The tomb was by the magnificent tomb of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and Blanche of Lancaster, between the pillars of the 6th bay of the Choir. (Benham) The Pembroke tomb was a magnificent structure consisting of effigies of the earl and his Lady Pembroke lying on a sarcophagus, attended by kneeling children, and the whole covered by an elaborate canopy resting on stone shafts. (Clinch) Her memorial there read: “a most faithful wife, a woman of the greatest piety and discretion” and “Her banners were set up over her arms set on divers pillars.“ On her tomb her epitath read that she had been “very jealous of the fame of a long line of ancestors.“ Her husband, Lord Pembroke, died on 17 March 1570 and by his wishes was also buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral on 18 April 1570 next to Lady Pembroke.

In her honor, in the old chapel at Wilton House was preserved a stained glass window in which were painted the kneeling figures of Lord Pembroke and his two sons also that of his wife Anne Parr and her daughter (also named Anne). The glass is now removed to the new Church at Wilton and will be found in the first window to the right on entering. Lady Pembroke is represented as wearing a rich mantle covered with her armorial bearings.

The lady’s mantle bears the following quarterings

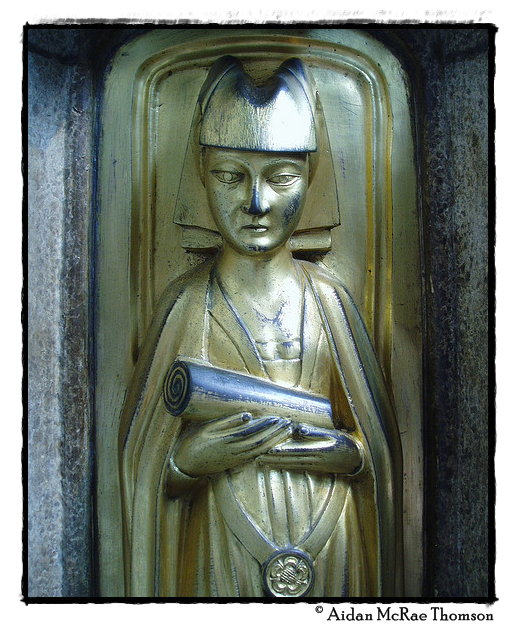

Detail of the magnificent tomb chest that bears the effigy of Richard Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick in the chapel he founded at St Mary’s, Warwick. This effigy is that of his daughter-in-law, Lady Cecily Neville.

She was most likely named after her paternal aunt, Lady Cecily Neville, later Duchess of York.[2] Her first cousins by the Duchess of York included Anne of York; Edmund, Earl of Rutland; Elizabeth of York; Margaret of York; George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence; and Kings Edward IV and Richard III. Other cousins included John Mowbray, 3rd Duke of Norfolk; Lord Humphrey Stafford, 7th Earl of Stafford [father of 2nd Duke of Buckingham]; Lady Katherine Stafford, Countess of Shrewsbury [wife of the 3rd Earl]; Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland; Ralph, 2nd Earl of Westmorland; George Neville, 4th and 2nd Baron of Abergavenny; Thomas Dacre, 1st Baron Dacre of Gillesland; and Ralph Greystoke, 5th Baron.

In 1436, it was decided that Cecily would marry Henry de Beauchamp, Lord Despenser (later 1st Duke of Warwick and King of the Isle of Wight, as well as of Jersey and Guernsey).[2] Henry was the son and heir of son of Richard de Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick and Lady Isabel le Despenser, the sole heiress of Thomas le Despenser, 1st Earl of Gloucester (d.1399) by his wife, Constance of York. At the same time, it was decided that her elder brother, Richard, would marry Beauchamp’s younger sister, Lady Anne.[2] The marriage negotiations were not easy or inexpensive; Salisbury had to promise to pay Warwick a large sum of 4, 700 marks (£3, 233.66).[2] In 1436, the two couples married in a double marriage ceremony.[2]

After the death of the Duke of Warwick in 11 June 1446, the Dowager Duchess married to Sir John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester. They had no children.

By the Duke of Warwick, Cecily gave birth to a daughter and their heiress, Lady Anne, who was most likely named after her aunt, who had married Cecily’s brother Richard [later known as “Warwick the Kingmaker”]. Richard’s wife, Lady Anne, would inherit the Beauchamp fortunes and became Countess of Warwick in “her own right” after the death of her niece in 1449.

The advantage of this marriage, which came in the form of Cecily’s husband being created Duke of Warwick on 14 April 1445, was short lived as her husband died on 11 June 1446 and the couple’s only daughter, Lady Anne Beauchamp, was allowed to succeed only as suo jure 15th Countess of Warwick. Upon the death of Cecily’s daughter in 1449, the title was inherited by her paternal aunt, also named Lady Anne Beauchamp. Lady Anne, who had married Cecily’s brother Sir Richard Neville, became suo jure 16th Countess of Warwick thus making Neville jure uxoris 16th Earl of Warwick. There were no objections as the elder half-sisters from the 13th Earl of Warwick’s marriage to his first wife, Elizabeth Berkeley; their husband’s, John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury and Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, were off defending Normandy.[2] The third half-sister had been married to George Neville, 1st Baron Latimer who had been declared insane and his brother Salisbury already possessed his lands.[2] The three sisters had to settle for nine manors, while the Despenser lands were preserved for George Neville, later 4th Baron Bergavenny, the heir of the 16th Countess of Warwick’s maternal sister, Lady Elizabeth Beauchamp, suo jure Baroness Bergavenny.[2] Cecily and her second husband, the Earl of Worcester, however had custody of the land up until two months before Cecily died in July 1540.[2] Upon that time, the lands were handed over to Cecily’s brother, Warwick.[2] However in 1457, when Bergavenny became of age — the rights were ignored and Warwick’s wife, Anne, became the sole heiress of her mother’s inheritance in the first parliament of Edward IV in 1461.[2] Both Warwick and Bergavenny were cousins to the King, however Warwick was the older brother of Bergavenny’s father. Warwick’s wife was also the daughter of the 13th Earl of Warwick, who was senior to his cousin, Richard Beauchamp, 1st Earl of Worcester — first husband of Lady Isabel le Despenser.

The Future of the Warwick Inheritance

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick was a supporter of the House of York as cousin to the King and his siblings. However, at the Battle of Barnet, Warwick and his brother-in-law, Oxford, both sided with the Lancastrian King.[2] Warwick’s allegiance to the House of York was damaged after Edward IV married the Lancastrian widow, Lady Elizabeth Grey [born Woodville]. As Lady Elizabeth’s large family followed her to court, so did the titles, marriages, and grants. The Woodvilles were of common descent, but their fortunes improved when a Woodville squire married the Dowager Duchess of Bedford [widow of John of Lancaster, son of Henry IV]. The marriage was not favored by the nobles at court and the favors granted to the Woodvilles did not stop–in that, the nobility became extremely frustrated and resentful. Warwick rebelled and paid the price with his life. His only children were two daughters. Warwick had no male heir. However, his two daughters both married a brother of King Edward IV and became Royal Duchesses. After the Battle of Barnet, Warwick’s wife Anne [the holder of the title Countess of Warwick and inheritance], forfeited her right to all of her inheritance due to being the wife of the traitor, Warwick. The inheritance was eventually divided between Warwick’s eldest daughter, Isabel, the Duchess of Clarence and Anne, who would become the Duchess of Gloucester [later queen consort]. The Duke of Clarence forfeited his right to any of the inheritance after his execution [his wife was already dead]. Their son, Edward, was imprisoned in The Tower and was executed by order of Henry VII in 1499.[7]

An ironic twist to the history of this Abbey came during the reign of the Tudor King Edward VI; the Manor of Tewkesbury, a possession of the Beauchamps, was granted to Lord Seymour of Sudeley. Sudeley was non other than the husband of the Dowager Queen Katherine Parr. Parr, herself, was a descendant of Warwick’s sister, Lady Alice; her paternal great-grandmother.[7]

Lady Cecily, the Dowager Duchess of Warwick and Countess of Worcester died on 26 July 1450. She was buried with her first husband, the Duke of Warwick, at Tewkesbury Abbey; with no monument.[1] Warwick was buried at his own request between the stalls in the choir upon his death in 1446. At the time the choir was repaved in 1875, a grave of stone filled with rubble was found together with some bones of a man of herculean size. These, no doubt, were those of the Duke who was buried here. The large marble slab that formerly covered the grave disappeared early in this century but the brasses that were originally in it had been taken away long before, Cecily, the Dowager Duchess of Warwick was buried in the same place on 31 July 1450.[3][4]

Effigy of John Tiptoft and his second and third wives, Elizabeth Greyndour and Elizabeth Hopton at Ely Cathedral

Beauchamp Chapel, Warwick. Also buried near this monument is Katherine Parr’s brother, the Marquess of Northampton whose funeral and burial was paid for by Elizabeth I.

Cuthbert Tunstall (c. 1474/5 Hatchford, Richmondshire, England – 18 November 1559 Lambeth Palace, London, England) was an English church leader during the reign of four Tudor monarchs. Through out his lengthy career he was Bishop of Durham, Bishop of London, Archdeacon of Chester, Lord Privy Seal, Royal adviser, and a diplomat. He was “lucky” enough to have served as Bishop of Durham [among other offices] and actually survive the reigns of three Tudor monarchs; King Henry VIII, Edward VI [Protestant], Mary I [Catholic]. Under the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I, Tunstall would be arrested in 1559 after refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy and die under house arrest at Lambeth Palace [home to the Archbishops of Canterbury].

“Tunstall’s long career of eighty-five years, for thirty-seven of which he was a bishop, is one of the most consistent and honourable in the sixteenth century. The extent of the religious revolution under Edward VI caused him to reverse his views on the royal supremacy and he refused to change them again under Elizabeth.” – The Anglican historian Albert F. Pollard

Tunstall was illegitimate at birth, although his parents later married and the irregular circumstances of his background were never held against him. He was the son of Sir Thomas Tunstall, one of two sons of Sir Thomas of Thurland. Sharing a great-great-grandfather, Sir Thomas of Thurland Castle [Tunstall’s grandfather], Tunstall was a first cousin, twice removed on his father’s side to Queen Katherine Parr and her siblings Lady Anne Herbert and Sir William, 1st Marquess of Northampton. Tunstall was appointed as the executor of Sir Thomas Parr’s will. After his death, Tunstall continued to stay close to the Parr family. Tunstall advised Lady Maud Parr on the education of her children; especially that of her daughters. Maud named Tunstall as one of the executors of her will as well.

Tunstall was an outstanding scholar and mathematician, he had been educated in England, spending time at both Oxford and Cambridge, before a six year spell at the University of Padua in Italy, from which he received two degrees. His Church career began in 1505, after he returned to England. He was ordained four years later. At the time of his ordination four years later he had caught the attention of the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham, who sponsored Tunstall’s advancement and brought him to court. Tunstall was also a close to Wolsey, who recognized his potential to serve his country and diplomacy.

Cuthbert Tunstall [a portrait painted before the Reformation showed him with a rosary. It was obviously painted over].

Tunstall was a great publisher of many books including De arte supputandi libri quattuor (1522), which enhanced his reputation among the leading thinkers of Europe. This book would be used later by Mary Tudor and his cousin Catherine Parr as queen.

Like More, Tunstall was on intimate terms with King Henry VIII. During the King’s ‘Great Matter‘, Tunstall defended Queen Katherine of Aragon, but not with the vigour or absolute conviction of Bishop Fisher. Tunstall had been bold enough to tell Henry that he could not be Head of the Church in spiritual matters and he may have been one of the four bishops of the northern convocation who voted against the divorce, but he recognized that the queen’s cause was hopeless and never attempted opposition to the King. In fact, he attended Anne Boleyn’s coronation. But Tunstall felt he could not keep quiet, he wrote a letter personally to Henry about the rejection of Christendom, and other matters that bothered him. Henry disagreed and refuted every point Tunstall made. These exchanges led to a search of Tunstall’s home by order of the King, but no incriminating evidence was found. Rumor was that Sir Thomas More warned Tunstall in time to dispose of anything that might incriminate him.

![Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall [right] confronts Katherine of Aragon in "The Tudors".](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/bishop-cuthbert-tunstall1.png)

Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall [right] portrayed by Gordon Sterne confronts Katherine of Aragon in “The Tudors“.

After the ‘great matter’ was resolved, Tunstall turned his loyalty back to the King. Tunstall was an executor of King Henry VIII’s will. Tunstall would go on to serve in the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I.

On 19 July 1553, Mary was proclaimed Queen. After being imprisoned in The Tower under the rule of Edward VI, Mary released him and he went back to being Bishop of Durham. During the reign of Mary, Tunstall was very lenient on the Protestants involved in the “Marian Persecutions.”

Lambeth Palace, London. The oldest parts of the present buildings date from the 1400’s. The most obvious external feature is the gatehouse which is framed on either side by two towers, built by in tudor brick by Archbishop Morton in 1495. This is consequently known as Morton’s Tower.

It was during Elizabeth’s reign that Tunstall refused to take Elizabeth’s Oath of Supremacy and was subsequently arrested. Even though he had been Elizabeth’s godfather, he was deprived of his diocese in September 1559, and held prisoner at Lambeth Palace, where he died within a few weeks, aged 85. He was one of eleven Catholic bishops to die in custody during Elizabeth’s reign. He was buried in the chancel of Lambeth church under the expense of the Archbishop that had overseen his confinement, Parker.

Thurland Castle Gate; Lancashire.gov.uk

Thurland Castle; Lancashire.gov.uk

De Morgan in his Arithmetical Books was laudatory about Tunstall: “This book is decidedly the most classical which was ever written on the subject in Latin, both in purity of style and goodness of matter. The author had read every thing on the subject, in every language which he knew … and had spent much time, he says, ad ursi exemplum, in licking what he found into shape. … For plain common sense, well expressed, and learning most visible in the habits it had formed, Tonstall’s book has been rarely surpassed, and never in the subject of which it treats”. As hinted by De Morgan, Tunstall’s work is not original, but a confessed compilation. Tunstall‘s motivation for writing it was a suspicion that that the accounts goldsmiths with whom he was dealing were incorrect; he renewed his study of arithmetic in order to check their figures. His work was the first printed in Great Britain to be devoted wholly to mathematics.This is the first of three 16th-century editions in De Morgan’s library. De Morgan’s designation of it on the title page as “very rare” has since been disproved: nineteen other copies are recorded in Britain on ESTC, chiefly held in Oxford and Cambridge libraries, with another five in North America. (DeMorgan Library, London)

In Durham Castle, Tunstall constructed a Chapel in 1540. For more info: Tunstall Chapel.