Control, Marriage, and Power in 16th-Century Germany

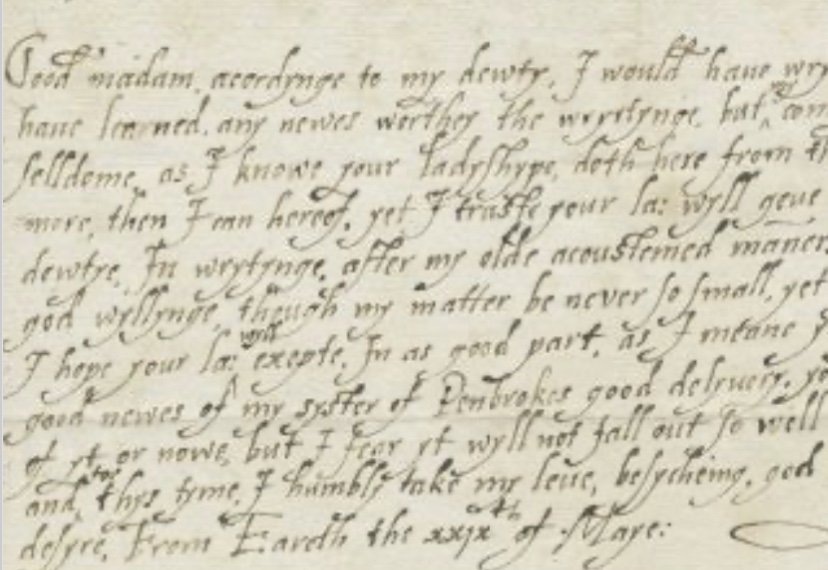

Eberwin III (1536 – 19 February 1562) was a German nobleman of the elder line of the House of Bentheim-Steinfurt. He ruled Bentheim and Steinfurt from 1544 until his death. From 1557 onward, he was also Count of Tecklenburg and Lord of Rheda — by marriage.

In 1553, at age 18, he married 21-year-old Anna of Tecklenburg-Schwerin, the heiress of Tecklenburg.

She was not a decorative bride.

She was a ruling heir.

When her father, Conrad of Tecklenburg-Schwerin, died, a dispute erupted over who held authority.

Anna asserted her right to rule suo jure — in her own name.

Eberwin claimed authority jure uxoris — by right of his wife.

This was not a marital disagreement.

It was a constitutional conflict over sovereignty.

Arrested for Ruling

When Anna refused to relinquish control of her inheritance, Eberwin escalated the matter dramatically.

He had her arrested and confined in her own residence, Tecklenburg Castle.

A ruling countess — imprisoned for asserting legal authority over her own lands.

Anna of Tecklenburg-Schwerin was confined in Tecklenburg Castle during her dispute with Eberwin III over whether she ruled suo jure (in her own right) or he ruled jure uxoris (by right of marriage).

And yet.

During her tenure, the castle underwent significant structural transformation under Anna’s direction.

What Changed Under Anna:

Outer windows were enlarged — increasing light and comfort. A new access road (today’s Schlossstrasse) was constructed. A new north-eastern entrance was created. The castle shifted from fortress mentality to stately residence.

In doing so, Tecklenburg lost some of its defensive strength.

Part of a bastion was buried beneath the embankment created for the new approach road.

That buried bastion wasn’t rediscovered until 1944 — accidentally uncovered while digging an air raid shelter.

Later, in the 17th century, the Mauritz Gate (Mauritztor) was built at this new entrance under Count Mauritz. Its lower levels and coat-of-arms frieze still survive.

Release from Imprisonment

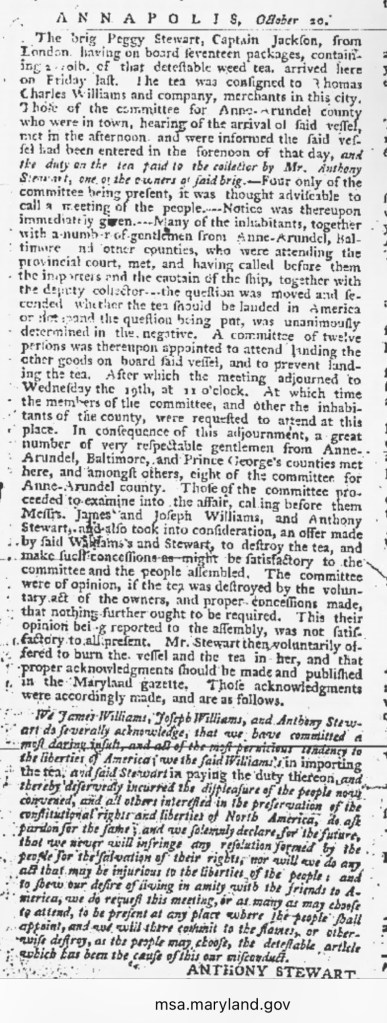

She was released only after intervention by Christopher of Oldenburg.

Following her release, the nobility of Tecklenburg sided with Anna. Eberwin was accused of adultery. Anna accused him of reckless financial excess — including luxury horses and the commissioning of his 1560 portrait by Hermann tom Ring.

After mediation by neighboring rulers, the couple agreed to a legal separation a mensa et thoro — “from bed and board.”

The Outcome

The conflict ended in 1562 when Eberwin died of syphilis at age 26.

He was succeeded by his infant son, Arnold III of Bentheim.

Under Anna’s regency.

Anna — the woman he attempted to confine and override — ultimately governed.

Why This Matters

This case illustrates a fundamental tension in early modern Europe:

When a woman inherited power in her own right, marriage did not automatically erase her sovereignty — but it could trigger conflict.

Anna of Tecklenburg asserted that inheritance did not dissolve into her husband’s authority.

And despite imprisonment, political pressure, and marital collapse, she retained her position.

Control, marriage, and power were deeply intertwined in the 16th century.

But Anna’s story makes one thing clear:

Women who ruled suo jure were not anomalies.

They were legal realities — even when challenged.

Power Struggles

Anna fought for suo jure authority in the 1550s.

But within decades, Tecklenburg’s autonomy would face larger structural threats from regional consolidation powers like Cleves where Queen Anne of Cleves was born.

It’s a classic small-county vs. rising territorial-state pattern in the Empire.

You see the long arc of:

Female inheritance dispute → male contestation → dynastic instability → regional consolidation pressures.

By the later 16th century, the Duchy of Cleves (Jülich-Cleves-Berg) was expanding influence across the Lower Rhine–Westphalia region.

Tecklenburg was a smaller but strategically important county.

After Anna’s regency period and the succession struggles involving her son Arnold III, Tecklenburg became entangled in territorial disputes with stronger neighboring powers — including Cleves.

Visibility and Power in 16th Century Portraits

In the 16th century, portraiture wasn’t just vanity — it was political propaganda. When someone like Eberwin commissions a formal portrait (like the 1560 one by Hermann tom Ring), he’s doing more than decorating a wall. He’s saying:

I rule. I possess status. I possess wealth. I control the narrative.

Anna, despite being the suo jure heiress, doesn’t get the same monumental visual legacy attached to her name.

That absence is telling.

Women who ruled in their own right often:

Appeared in smaller devotional portraits Were depicted within marriage imagery Or were visually erased unless politically necessary

Meanwhile, men in jure uxoris claims rushed to commission grand, standalone, armor-or-velvet portraits to solidify authority.

It’s narrative control in oil paint.

And here’s the irony in Anna’s case:

He commissions the portrait.

He spends lavishly.

He tries to imprison her.

He dies at 26.

She governs.

History kept her power, even if the canvas didn’t.

Sources

• Wikipedia (with regret, sigh) don’t do it kids! 😂