By Meg Mcgath, 22 March 2023 *be kind and if you find info here…leave breadcrumbs. Thanks!*

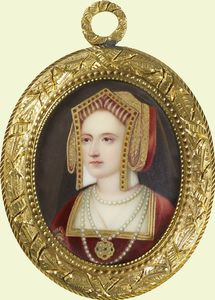

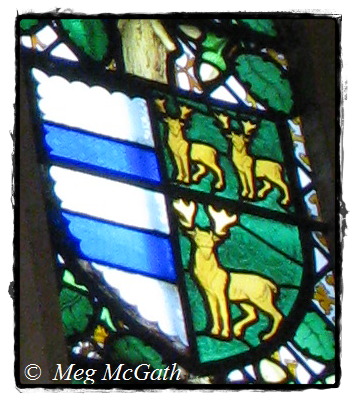

Lady Maud Parr, (6 April 1492 – 1 December 1531) was the wife of Sir Thomas Parr of Kendal, Knt. She was the daughter and substantial coheiress of Sir Thomas Green of Greens Norton, Northamptonshire. The Greens had inhabited Greens Norton since the fourteenth century. Green was the last male heir, having had two daughters. Her mother is named as Joan or Jane Fogge. However, I haven’t been able to prove her parentage. According to Linda Porter, Katherine Parr is a great-granddaughter of Sir John Fogge. When asked for a source, Porter said it came from Dr Susan James. In her biography on Katherine, Susan James states, “he [Green] had made an advantageous with the granddaughter of Sir John Fogge, treasurer of the Royal household under Edward IV”. Fogge was married to Alice Haute (or Hawte), a lady and cousin to Edward’s queen, Elizabeth. By her father, Maud descended from King Edward I of England multiple times. Her sister, Anne, would marry Sir Nicholas Vaux (later Baron). Vaux married firstly to Maud’s would be mother-in-law, the widowed Lady Elizabeth Parr, by whom he had three daughters including Lady Katherine Throckmorton, wife to Sir George of Coughton. Her father spent his last days in the Tower and died in 1506 trumped up on charges of treason.

Ten months after the death of her father, the fifteen year old Maud became a ward of Thomas Parr of Kendal (c.1471/1478 (see notes)-1517) a man nearly twice her age. Around 1508, Maud married to Thomas, son of Sir William Parr of Kendal (1434-1483) and Elizabeth FitzHugh (1455/65-1508), later Lady Vaux. At the time, he was thirty seven while she was about sixteen. He would become Sheriff of Northamptonshire, master of the wards and comptroller to King Henry VIII. He would become a Vice chamberlain of Katherine of Aragon’s household. When Princess Mary was christened, he was one of the four men to hold the canopy over her. He would become a coheir to the Barony of FitzHugh in 1512 and received half the lands of his cousin, George, 7th Baron (d.1512). Had he lived, he most likely would have received the actual title as a favored courtier. The barony is still in abeyance.

Maud became a lady to Queen Katherine of Aragon along with Lady Elizabeth Boleyn, mother of the future Queen Anne. It seems as though the Parrs and Boleyns were indeed in the same circle around the king—something rarely noted! Both Thomas Boleyn and Thomas Parr were knighted in 1509 at the coronation of King Henry VIII and Queen Katherine of Aragon.

Maud’s relationship with the Queen was a relationship that went much deeper than “giddy pleasure”. Both knew what it was like to lose a child in stillbirths and in infancy. It was Katherine Parr’s mother, Maud, who shared in the horrible miscarriages and deaths in which Queen Katherine would endure from 1511 to 1518. The two bonded over the issue and became close because of it. Lady Parr became pregnant shortly after her marriage to Sir Thomas Parr. Most people think that Katherine Parr, the future queen and last wife of Henry, was the first to be born to the Parrs; not so. In or about 1509, a boy was born to Maud and Thomas. The happiness of delivering an heir to the Parr family was short lived as the baby died shortly after — no name was ever recorded. It would be another four years before Maud is recorded as becoming pregnant again. In 1512, Maud finally gave birth to a healthy baby girl. She was christened Katherine, after the queen, and speculations are that Queen Katherine was her godmother. In about 1513, Maud would finally give birth to a healthy baby boy who was named William. Then again in 1515, Maud would give birth to another daughter named Anne, possibly after Maud’s sister.

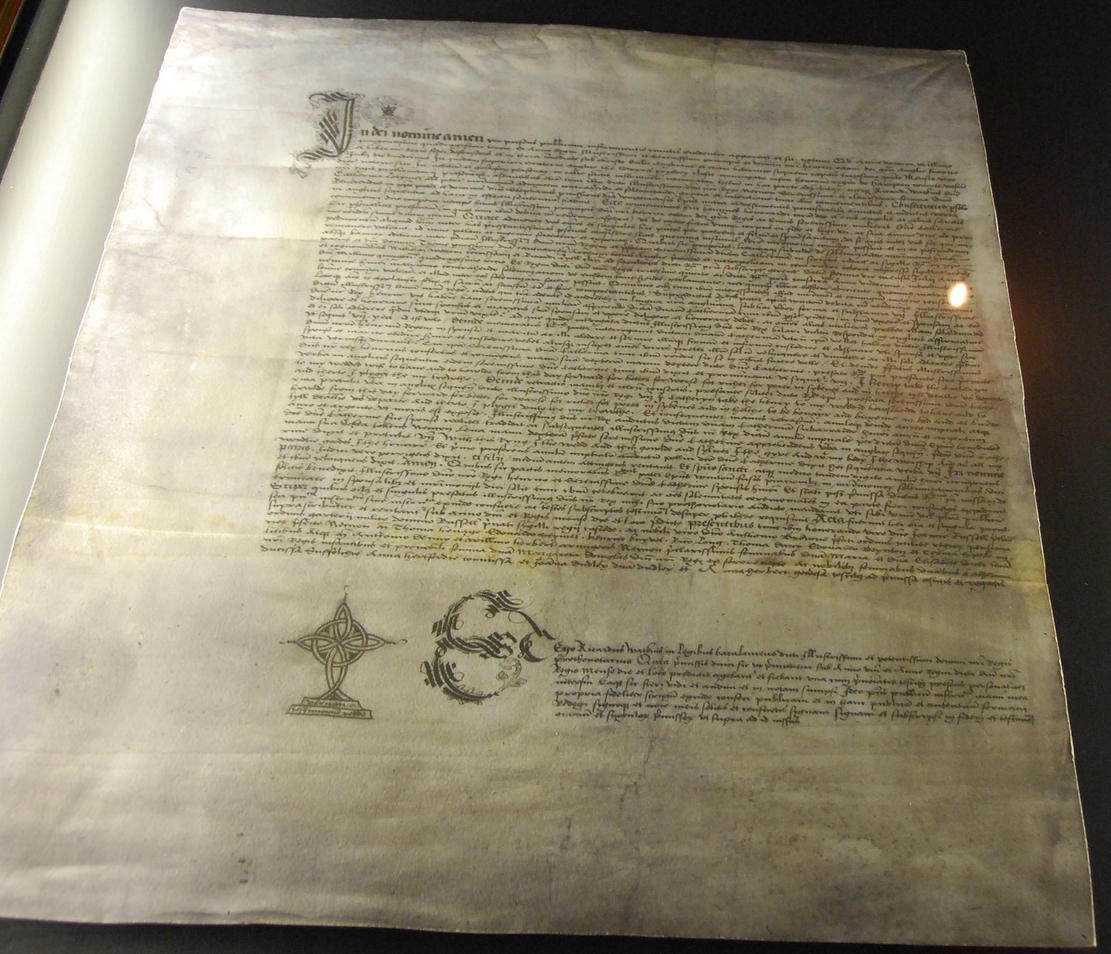

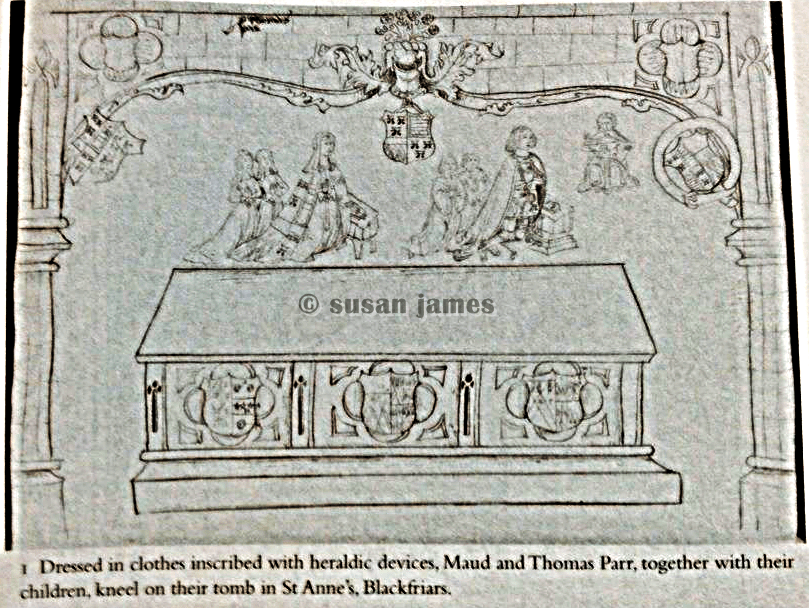

In or about 1517, Maud became pregnant again. It was in autumn of that year that her husband, Sir Thomas, died at his home in Blackfriars of the sweating sickness. Maud was left a young widow at 25, with three small children to provide for. It is believed that the stress from his death caused the baby to be lost or die shortly after birth. No further record of the child is recorded. In a way Maud might have been relieved. He left a will, dated 7 November, for his wife and children leaving dowry’s and his inheritance to his only son, William, but as he died before any of his children were of age, Maud along with Cuthbert Tunstall, their uncle Sir William Parr, and Dr. Melton were made executors. He left £400 apiece as marriage portions for his two daughters. He provided for another son and if the baby was “any more daughters”, he stated “she [Maud] shall marry them at her own cost”. In his will, Parr mentions a signet ring given to him by the King which illustrates how close he was to him. He was buried in St. Anne’s Church, Blackfriars, beneath an elaborate tomb. His tomb read, “Pray for the soul of Sir Thomas Parr, knight of the king’s body, Henry the eigth, master of his wards…and…Sheriff…who deceased the 11th day of November in the 9th year of the reign of our sovereign Lord at London, in the Black Friars..” Maud chose not to remarry for fear of jeopardizing the huge inheritance she held in trust for her children. She carefully supervised the education of her children and studiously arranged their marriages.

In October 1519, Maud was given her own quarters at court. From 7 to 24 June 1520, Maud attended the queen at The Field of the Cloth of Gold, the meeting between King Henry VIII and King Francis I of France. Her sister, Anne, now Lady Vaux, and her husband, Nicholas, along with her other in laws, Lord Parr of Horton and his wife, were also present.

According to this article, which states no sources,

“In 1522, Maud was assessed for a “loan” to the King for the French Wars, of 1,000 marks, a very substantial sum, the same as the amount provided by Lord Clifford. She appears in the various household accounts of Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon as entitled to breakfast at Crown expense and to suits of livery for her servants, as well as lodgings, which were very hard to come by.

In 1523, Maud started writing letters to find a suitable husband for her daughter, Katherine. Henry le Scrope (c.1511-25 March 1525), son and heir to Sir Henry le Scrope, 7th Baron Scrope of Bolton by his wife Mabel Dacre, was a cousin. The negotiations lead to nothing. By 1529, Maud found a match for her daughter in Sir Edward Borough, son of Sir Thomas.

When regulations for the Royal household were drawn up at Eltham, in 1526, Lady Parr, Lady Willoughby and Jane, Lady Guildford were assigned lodgings on “the queen’s side” of the palace. If an emergency arose, yeoman were sent with letters from the queen “warning the ladies to come to the court”. Maud was still listed, along with only five other ladies, which included the King’s sister, as having the privilege of having permanent suites in 1526. Maud was friendly with the King as well—her husband had been a favored courtier—and gifted him a coat of Kendal cloth in 1530. She was gifted miniatures of the King and Queen from the Queen herself.

In the summer of 1530, Maud visited her daughter, now Lady Katherine Borough, in Lincolnshire. She stayed at her own manor in Maltby, which was eighteen miles from Old Gainsborough Hall. It is thought that her presence there influenced Sir Thomas Borough to give his son, Edward, a property in Kirton-in-Lindsey. This gave Katherine an opportunity to manage a household of her own.

Maud continued her position at court as one of Katherine of Aragon’s principal ladies and stayed close to the Queen even when her relationship with the king started to decline. Henry’s infatuation with Anne Boleyn, one of the Queen’s ladies, became apparent and inevitably the ladies began to take sides. In these times, Queen Katherine never lost the loyalty and affection of women like Maud Parr, Gertrude Courtenay, and Elizabeth Boleyn, who had been with the Queen since the first years of her reign. At the time of her death, Maud was still attending Queen Katherine.

Maud died on 1 December 1531 at age thirty nine and is buried in St. Ann’s Church, Blackfriars Church, London, England beside her husband.

“My body to be buried in the church of the Blackfriars, London. Whereas I have indebted myself for the preferment of my son and heir, William Parr, as well to the king for the marriage of my said son. As to my lord of Essex for the marriage of my lady Bourchier, daughter and heir apparent to the said Earl. Anne, my daughter, Sir William Parr, Knt., my brother, Katherine Borough, my daughter, Thomas Pickering, Esq., my cousin and steward of my house.”

In her will, dated 20 May 1529, Maud designated that she wanted to be buried Blackfriars where her husband lies if she dies in London, or within twenty miles. Otherwise, she could be buried where her executors think most convenient. Maud left her daughter, Katherine, a jeweled cipher pendant in the shape of an ‘M’. Maud also left Katherine a cross of diamonds with a pendant pearl, a cache of loose pearls, and, ironically, a jeweled portrait of Henry VIII. To her daughter, Anne, she left 400 marks in plate and a third share of her jewels. The whole fortune, Lady Parr had directed, was to be securely chested up ‘in coffers locked with divers locks, whereof every one of them my executors and my … daughter Anne to have every of them a key’. ‘And there’, Lady Parr’s will continued, ‘it to remain till it ought to be delivered unto her’ on her marriage. She also provided 400 marks for the founding of schools and “the marrying of maidens and especial my poor kinswomen”. Cuthbert Tunstall, who was the principal executor of Maud’s will, she left to “my goode Lorde Cuthberd Tunstall, Bisshop of London…a ring with a ruby”. Tunstall had been an executor of her late husband’s will as well. An illegitimate son of Sir Thomas of Thurland Castle, he was a great-nephew of Alice Tunstall, paternal grandmother to Sir Thomas Parr. To her daughter-in-law, Anne, she left substantial amounts of jewelry, “to my lady Bourchier when she lieth with my son” as a bribe to get the marriage consummated. Maud also left a bracelet set with red jacinth to her son, William. She begs him “to wear it for my sake”. Maud was also stated in her will, “I have endetted myself in divers summes for the preferment of my sonne and heire William Parr as well”. For her cousin, Alice Cruse, and Thomas Parr’s niece, Elizabeth Woodhull or Odell, Maud left “at the lest oon hundrythe li”. She wills her “apparrell [to] be made in vestments and other ornaments of the churche” for distribution to three different parish churches which lay close to lands that she controlled. She bequeathed money to the Friars of Northampton. For centuries, historians have confused the first husband of her daughter, Katherine, with his elder grandfather, Edward, the 2nd Baron Borough or Burgh of Gainsborough (d.August 1528). He was declared insane and was never called to Parliament as the 2nd Baron Borough. Some sources mistakenly state she was just a child at the time of her wedding in 1526. Katherine’s actual husband, Sir Edward Borough (d.1533), was the eldest son and heir of the 2nd Baron’s eldest son and heir, Sir Thomas Borough, who would become the 1st Baron Borough under a new writ in December 1529. Katherine and Edward were married in 1529. At the time, Thomas Borough was still only a knight. Maud mentions in her will, Sir Thomas, father of the younger Edward, saying ‘I am indebted to Sir Thomas Borough, knight, for the marriage of my daughter‘. Edward was the eldest son and heir to his father, Sir Thomas, Baron Borough. He would die in 1533. Maud’s will was proved 14 December 1531.

Maud and Thomas had three children to survive infancy.

Katherine or “Kateryn” (1512-1548), later Queen of England and Ireland, would marry four times. In 1529, Katherine married Sir Edward Borough. He died in 1533. In 1534, Katherine became “Lady Latimer” as the wife to a cousin of the family, Sir John Neville, 3rd Baron Latimer (of Snape Castle). He was dead by March 1543. A few months later, on 12 July, Katherine married King Henry VIII at Hampton Court Palace. The king died in January 1547. In May of that year, Katherine secretly wed Sir Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour (d.1549) of Sudeley Castle, a previous suitor from 1543. Their love letters still survive. By Seymour, Katherine had a daughter, Mary. Katherine died 5 September 1548. Seymour would be executed 20 March 1549 for countless treasonous acts against the crown (his nephew was King Edward VI).

William (1514-1571) married on 9 February 1527, at the chapel of the manor of Stanstead in Essex, to Anne Bourchier, suo jure 7th Baroness Bourchier (d. 26 January 1571), only child and heiress of Henry Bourchier, 2nd Earl of Essex (d.1540). In 1541, she eloped from him, stating that “she would live as she lusted”. Susan James states the next year, Parr secured a legal separation. James also states that on 13 March 1543, a bill was passed in Parliament condemning Anne’s adulterous behavior and declaring any children bastards. Wikipedia states “On 17 April 1543 their marriage was annulled by an Act of Parliament and any of her children “born during esposels between Lord and Lady Parr””(there were none) were declared bastards. The source is G. E. Cokayne, ”The Complete Peerage”, n.s., Vol.IX, p.672, note (b). I have not been able to access The Complete Peerage to confirm. On 31 March 1551, a private bill was passed in Parliament annulling Parr’s marriage to Anne. She predeceased Parr by a few months. William married Elisabeth Brooke (1526-1565), a daughter of George Brooke, 9th Baron Cobham of Cobham Hall in Kent, by his wife Anne Bray. A commission ruled in favour of his divorce from Anne shortly after he married Elizabeth Brooke in 1547, but Somerset punished Parr for his marriage by removing him from the Privy Council and ordering him to leave Elizabeth. The divorce was finally granted in 1551, and his marriage to Elizabeth was made legal. On 31 Mar 1552, a bill passed in Parliament declaring the marriage of Anne Bourchier and Parr null and void. Their marriage was declared invalid in 1553 under Queen Mary and valid again in 1558 under Queen Elizabeth who adored William. Each change of monarch, and religion, changed Elizabeth’s status. She died in 1565. William married Helena Snakenborg in May 1571 in Elizabeth’s presence in the queen’s closet at Whitehall Palace with pomp and circumstance. Parr would die 28 October 1571.

Anne (1515-1552) who married Sir William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke in 1538. They had three children: Henry, Edward, and Anne. They are ancestors to the current Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery, Earl of Carnarvon, Earl of Powis, Marquess of Abergavenny, and other nobility.

Notes

Porter, James, and Mueller state Thomas Parr was born in 1478. However, in James’s biography of Katherine, she states he was 37 at the time of his marriage to Maud Green in 1508. So that would be about 1471, right?

References

Susan James. “Catherine Parr: Henry VIII’s Last Love”, 2010. Google eBook (preview)

Susan James. Women’s Voices in Tudor Wills, 1485–1603: Authority, Influence and Material Culture, 2016. Google eBook (preview)

Meg McGath. “Childbearing: Queen Katherine of Aragon and Lady Maud Parr”, 2012.

Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondence, ed. Janel Mueller, 2011. Google eBook (preview)

Sir Nicholas Nicolas. Testamenta Vetusta: being illustrations from wills, of manners, customs, … as well as of the descents and possessions of many distinguished families. From the Reign of Henry II. to the accession of Queen Elizabeth, Volume 2, 1826. Google eBook

Elizabeth Norton. “Catherine Parr

Wife, Widow, Mother, Survivor, the Story of the Last Queen of Henry VIII”, 2010. Google eBook (preview)

Linda Porter. Katherine the Queen: The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin Publishing, 2010)

Douglas Richardson. Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, 2nd Edition, 2011. Google eBook (preview)

Gareth Russell. Young and Damned and Fair: The Life of Catherine Howard, Fifth Wife of King Henry VIII, 2017. Pg 215. Google eBook (preview)

Agnes Strickland. Lives of the Queens of England, from the Norman Conquest With Anecdotes of Their Courts, Volumes 4-5, 1860. Pg 16. Google eBook

Tudor and Stuart Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty, ed. Aidan Norrie, Carolyn Harris, Danna R. Messer, Elena Woodacre, J. L. Laynesmith, 2022. Google eBook (preview)

The Antiquary: A Magazine Devoted to the Study of the Past, volume 24, 1891. Google eBook

The Reliquary, Volume 21, 1881. Google eBook