Category Archives: The Dowager Queen Katherine (1547-1548)

Queen Katherine Parr: Pregnant, At Last!

Katherine Parr (Deborah Kerr) and Lord Seymour (Stewart Granger) in “Young Bess” (1953); A Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Picture.

In December of 1547, Queen Katherine Parr became pregnant for what most people believe to be the first time by her fourth and final husband, Sir Thomas Seymour. After four husbands and twenty years of marriage, Katherine was about to fulfill what she felt was the primary duty of a wife, to give birth to a healthy baby; boys being preferred in aristocratic circles. Like today, some titles still cannot be inherited by the eldest or only daughter of a peer; meaning a girl cannot inherit the title of her father which is usually then passed to the closest living male relative, that being usually an uncle or cousin.

Katherine Parr (Deborah Kerr), Lord Seymour (Stewart Granger), and Lady Elizabeth (Jean Simmons) in “Young Bess” (1953).

Queen Katherine found pregnancy difficult. She still had an on-going feud with her brother-in-law, the Lord Protector and his rather nasty wife, had morning sickness, was constantly worrying about her step-daughter Lady Elizabeth, and the temper of her husband and lack of discretion towards his feelings for Lady Elizabeth must have made the early months of pregnancy extremely hard for the Queen Dowager.[1] In 1549, after the death of the Queen, two cramp rings for use against the pains of childbirth and three pieces of unicorn horn, sovereign remedy for stomach pains, were found in the chest of Katherine’s personal belongings which were talismans most likely from her husband and friend’s to alleviate the pains of childbirth and anticipated pangs of childbirth. Katherine was almost thirty-six, an advanced age to begin a pregnancy. The emotional strain of her household with Seymour’s infatuation with Lady Elizabeth couldn’t have helped her early months either.

As Katherine’s pregnancy progressed, her involvement in politics, if not her interest, diminished. She viewed her approaching motherhood with delight despite knowing the risks and the possibility that death in child birth was a very real possibility.

Compiled digital art featuring Hampton Court’s Katherine Parr over looking the gardens and Chapel on the grounds at Sudeley Castle. © Meg McGath, 2012.

Seymour decided that Katherine should be confined as far away possible from the press of business and turmoil of the court as well as the summer plagues of London. Katherine was taken to Sudeley Castle in Winchcombe, England, outside of Cheltenham. The castle has a long history stretching back to William de Tracy. Richard III used the castle as campaign headquarters during the Battle of Tawkesbury; in which Katherine’s grandfather fought. Upon the death of Richard III, the castle reverted to the crown and new monarch, Henry VII; who gave the castle to his uncle, Jasper Tudor. After the death of Jasper Tudor, Sudeley reverted to the crown again, to King Henry VIII. In fact, the King made a visit to the castle with Anne Boleyn in 1535. Upon the ascension of Edward VI, Sir Thomas was created Lord Seymour of Sudeley and was granted the castle. In preperation for her lying-in, Seymour spent 1,000 pounds having the rooms prepared for her in his newly aquired house at Sudeley in Gloucestershire.[2] With beautiful gardens and walks, the castle would have been a perfect place for Katherine to spend the last three months of her pregnancy.

One of several plaques on the wall in the exhibit for Katherine Parr at Sudeley. © Meg McGath, 2012.

On Wednesday, 13 June 1548, Seymour accompanied his wife, who was now six months pregnant, and his young ward, Lady Jane Grey, from Hanworth to Sudeley Castle in Gloucestershire. Lady Elizabeth Tudor had been sent away that Spring so she did not accompany them. In this castle, Katherine spent the last three months of her pregnancy and the last summer of her life. Typical of Queen Katherine, she spared no expense when it came to attendants. She was attended by her old friend and doctor, Robert Huicke, and was surrounded by other old friends, Miles Coverdale, her chaplain, her almoner, John Parkhurst, Sir Robert Tyrwhitt, and the ladies who had been with her over the years such as Elizabeth Trywhitt and Mary Wodhull. Katherine also had a full compliment of maids-of-honour and gentlewomen as well as 120 gentlemen and yeomen of the guard. In spite of his duties, Sir Thomas Seymour seems to have spent most of that summer with his wife. Katherine whiled away her summer days overseeing the education of Lady Jane Grey while preparing for her baby. Her affections for her husband seemed as strong as ever, as was her belief in the final analysis, Seymour would make the moral choice over the immoral one.

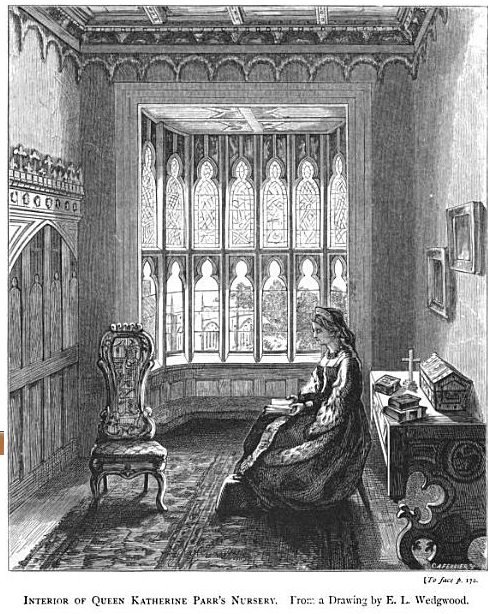

While Katherine awaited her confinement, Katherine continued decorating the nursery which overlooked the gardens and the Chapel. The nursery of an expected heir was done up in crimson and gold velvet and taffeta, with furniture and plate enough for a royal birth. In Seymour’s eyes, the child would be a member of the royal family as Katherine was still officially the only queen in England. After his daughter’s birth, Seymour was overheard telling Sir William Sharington that,

“it would be strange to some when his daughter came of age, taking [her] place above [the duchess of] Somerset, as a queen’s daughter.”[3]

Besides the baby’s cradle was a bed with a scarlet tester and crimson curtains and a separate bed for the nurse.

The Queen’s Gardens at Sudeley Castle; Katherine Parr would spend her final days walking with Lady Jane Grey in these gardens. © Meg McGath, 2012.

The Queen continued to take the advice of her doctor and walked daily among the grounds of Sudeley, but she was still concerned about the politics and overseeing of the new boy king.

On the eve of August 30th, Katherine went into labour.

Sources

- Linda Porter. ‘Katherine, the queen,’ Macmillan, 2012.

- Susan James. ‘Catherine Parr: Henry VIII’s Last Love,’ The History Press, Gloucestershire, 2008, 2009 [US Edition].

- Janel Mueller. ‘Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondences,’ University of Chicago Press, Jun 30, 2011.

- Emma Dent. ‘Annals of Winchcombe and Sudeley,’ London, J. Murray, 1877. Out of copyright; use of images and info.

The original post from which this was taken

- Meg McGath. “Queen Katherine Parr: The Pregnancy and Birth of Lady Mary Seymour“, WordPress, 29 August 2013.

The Men Who Took Power

“It is difficult to say for how long Warwick had been casting envious eyes on supreme power, and exactly when he gave serious thought to undermining the Protector; but that former friendship of which Somerset was soon to remind him had never gone very deep, and it evaporated entirely when at the beginning of the new reign Somerset took from him the coveted post of Lord High Admiral, and gave it to Thomas Seymour. Certainly Warwick was scheming against the Protector at the time of Thomas’ nefarious deeds. He quickly realized that by stirring the brotherly quarrel to its ultimate disastrous conclusion he must weaken Somerset’s standing in the country,, for there were many who, unaware of the full extent of Thomas’s treachery, and the unenviable position into which some members of the Council had manoeuvered the elder brother, regarded the affair as little short of fratricide. More recently Warwick had been in direct conflict with the protector over Somerset’s refusal to remove a justice in favour of Warwick’s nominee, and to grant his son, Ambrose, the reversion of two offices held by Sir Andrew Flammock.” -William Seymour; Ordeal by Ambition: An English Family in the Shadows of the Tudors

Not to undermine Seymour’s work but I don’t agree with him on this point. Thomas Seymour wasn’t exactly patient when it came to plotting and although I don’t agree with his reasons, or Dudley and Grey’s reasons for turning their backs against the Protector, they had valid reasons.

Thomas Seymour married before everyone told him it was a bad idea, or perhaps he didn’t care. Knowing what we know about Tommy, it was probably the latter. A century later somebody had done the same with Catherine of Valois, the Queen Dowager of England and mother to the baby-king Henry VI of England and II of France. Owen Tudor paid dearly for this, and although he got off in the end and proved himself to be a loyal Lancastrian, there were still consequences. Kathryn Parr was not as royal as Catherine of Valois had been but she had noble and Roya blood, and she was an important figure in the English Reformation. Edward VI loved her and Elizabeth looked up to her.

Thomas had always been ambitious and probably resented that he wasn’t being given as much honors as his brother was receiving. Not only that, some historians like Warwick dispute the allegations from later chroniclers that their wives quarreled over precedence and Anne asked Kathryn to give up her jewels. I love Warnicke and once again, I am not trying to put down their research, but I do think there was some form of quarrel between the two. Anne was as pragmatic as Kathryn was. She knew how dangerous Thomas was, and what he was doing and probably saw Katherine as a danger. That her influence over all these wards (who had royal blood and a claim to the throne) could be detrimental to her husband and what affected him, directly affected her and her children.

Also, she must have felt more important than the Queen Dowager since she married Thomas Seymour who despite his appointments and new title, was still several ranks lower than his older brother.

John Dudley was a staunch Protestant but a cold pragmatist when it came to war and foreign relations unlike Edward Seymour. The latter was following the same disastrous foreign policy of his predecessor, Henry VIII of invading Scotland, causing more death and destruction that supposedly would have intimidated them and forced the country into submission but what ended up happening was the opposite. As for his countrymen though, Edward showed he had better intentions than his opponent and former ally. Dudley wanted a more religious regime like the King, but Edward Seymour believed there should be compromise. (Another person who thought like this was Cranmer.) He tried pushing for policies that helped the poor and the needy but most of them did very little to improve the economy.

Edward’s intentions were good, but his way of doing things were not. When he was elected Lord Protector, his supporters thought that he was going to work for them instead of the common people and it ended turning the other way around. Edward could have succeeded in his domestic policies if he had been a better politician and not done many things (such as slapping one courtier) that ended up alienating him from the nobles and turned them against him. Furthermore, he refused to rule with the same iron fist as his predecessor. The ruthlessness he showed on Scotland, was something he was averse to showing on his fellow countrymen, even his enemies. Whereas with Dudley, it was the complete opposite.

Lastly, William Seymour like so many biographers that have become enchanted with their subjects, is against speaking too ill of him. He points out his flaws, his disastrous policies but he always adds that a lot of these are due to the nobles ceaselessly plotting against him. This is partially true as I’ve already stated, but he was also to blame.

Thomas was ultimately executed, Edward suffered the same fate years prior. The charges laid against him were outrageous, going so far as to plotting the murder of John Dudley, newly elevated to Duke of Northumberland. There’s no question that Edward did want to escape and was concocting all kinds of schemes to get out. Even going so far as to use his daughter Jane to entice the King and Jane was as Jane Grey, an accomplished young girl. A few years younger than her, she had translated and written many religious works. But his rivals sustained that he had plotted to invite everyone to a dinner and murder everyone there. Eventually new charges were laid on him were because the others weren’t enough to convict him. On November, Northumberland put all the evidence together and laid out the new charges against him. They were read out, and as it was customary of the time, the accused did not have to be present for his guilt to be established. Ned Seymour was accused with sedition, treason and conspiracy to “overthrow the government, imprison Northumberland and Northampton, and convene Parliament”.

Ned Seymour was able to show himself at the hearings at last in December. Lord Strange was one of the witnesses who was brought in, to accuse him of plotting to marry his young daughter, the nine year old Jane Seymour –an accomplished young woman, who as the other Jane [Grey], could read, write in Latin, Greek and many other languages, and had already translated many works- to the King. As ludicrous as all these charges were, this one was not. Ned Seymour did ask some of his allies to speak favorably of his daughter to the King, in the hopes that the young King would be impressed by her and this would release him [and his wife] from prison.

After this trial and his sentence was pronounced, Ned Seymour finally gave up. He knew the end was coming and prepared for the inevitable, praying hard and taking shelter as so many before him had done, in the religion that comforted him. There are a lot of version of his last words, one of them come from his chaplain, a man he largely favored, John Foxe. John was not present during his execution but he maintained that his account was taken from a “certain noble personage” who was.

His last words were: “Dearly beloves maisters and friends, I am brought hither to suffer, albeit that I never offended against the King neither by word nor deed, and have been always as faithful and true unto this realm as any man hath been. But forsomuch as I am by a law condemned to die, I do acknowledge myself, as well as others, to be subject thereunto …” Then he told them he had come to die, according to the law and gave thanks “unto the divine goodness, as if I had received a most ample and great reward” and asked them to continue to embrace the new religion.

Why was the Warwick Earldom given to the Dudleys? I should check the ancestry there. I’m sure there were senior lines but the “regency council” just handed out titles like candy. The death of Henry VIII — or even Edward IV — put an end to the rightful ways of nobility and male inheritance. What a joke. Henry was so stupid to entrust men over someone like Katherine Parr who had the best interests in mind when it came to Edward VI. But hey, there is speculation about Henry’s will which may have been altered. The men around Henry purposely kept the queen and Lady Mary away from the King and when he died…they weren’t told for days!! Those men thought they were helping, but in actuality–THEY killed the Tudor dynasty in a way.

6 AUGUST 1552: THE DEATH of Sir George Throckmorton of Coughton

The Tudor gate at Coughton Court, Warwickshire, England. Commissioned by Sir George. [Source: National Trust Coughton Court]

George was a loyal subject to the crown, however when it came to Henry’s divorce from Katherine of Aragon he opposed it. He did not approve of Henry marrying Anne Boleyn and was vocal about it. After all, he was close to Sir Thomas More and the Throckmorton was a devout Catholic family [still are to this day]. George’s circle included supporters of Katherine of Aragon which included Lady Maud Parr, his sister-in-law [wife to Sir Thomas Parr, brother of his wife Katherine]. Maud stayed with her mistress until her death in 1531.

Later on, George was steward from 1528-40 for Thomas Seymour, [later Baron Seymour of Sudeley]. The marriage of Katherine Parr to King Henry VIII in 1543 proved helpful to his children, but George was still in disfavor at court. George was part of the fall of Thomas Cromwell, but his part in it is obscure. Cromwell had somewhat kept George in disfavor for quite some time. The two clashed on religious ideals and other matters of state. The Throckmortons who had converted to Protestantism were held high at court and helped out their cousin Katherine Parr during her reign as queen and as dowager queen. Several Throckmortons did stick to the “old” religion and later found themselves in trouble during the reign of Elizabeth I [daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn].

Family

By 1512, George married Katherine, daughter of Sir Nicholas Vaux [later 1st Lord Vaux of Harrowden] and his first wife, Elizabeth FitzHugh. Elizabeth FitzHugh was the paternal grandmother of Queen Katherine Parr; daughter of Lady Alice FitzHugh [born Neville, granddaughter of Lady Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland]. The couple had eight sons including Anthony, Clement, George, John I, Kenelm, Nicholas and Robert and eleven daughters.

Throckmorton died on 6 August 1552 and was buried in the stately marble tomb which he had prepared for himself in Coughton church. The most impressive monument which he left, however, was the gatehouse of Coughton court. Throckmorton spent most of his life rebuilding the house: in 1535 he wrote to Cromwell that he and his wife had lived in Buckinghamshire for most of the year, ‘for great part of my house here is taken down’. In 1549, when he was planning the windows in the great hall, he asked his son Nicholas to obtain from the heralds the correct trickling of the arms of his ancestors’ wives and his own cousin [and niece by marriage] Queen Katherine Parr. The costly recusancy of Robert Throckmorton and his heirs kept down later rebuilding, so that much of the house still stands largely as he left it.

Wenceslas Hollar’s depiction of the heraldry at Coughton Court. The additions were made by Sir George.

References

- The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558, ed. S.T. Bindoff, 1982. ‘THROCKMORTON, Sir George (by 1489-1552), of Coughton, Warws.‘

Queen Katherine Parr: The First Woman and Queen of England to be Published

“Prayers or Meditations” by Queen Katherine Parr at Sudeley Castle. Photo by Meg Mcgath (2012).

First published in 1545, “Prayers or Meditations” by Queen Katherine Parr became so popular that 19 new editions were published by 1595 (reign of Elizabeth I). This edition was published in 1546 and bound by a cover made by the Nuns of Little Gedding. Located at Sudeley Castle, Winchcombe.

Queen Katherine Parr published two books in her lifetime. The first, ‘Prayers and Meditations’, was published while King Henry VIII was still alive [1545].

![Folger Shakespeare Library PDI Record: --- Call Number (PDI): STC 4824a Creator (PDI): Catharine Parr, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1512-1548. Title (PDI): [Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions] Created or Published (PDI): [1550] Physical Description (PDI): title page Image Root File (PDI): 17990 Image Type (PDI): FSL collection Image Record ID (PDI): 18050 MARC Bib 001 (PDI): 165567 Marc Holdings 001 (PDI): 159718 Hamnet Record: --- Creator (Hamnet): Catharine Parr, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1512-1548. Uniform Title (Hamnet): Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions Title (Hamnet): Praiers Title (Hamnet): Prayers or meditacions, wherein the minde is stirred, paciently to suffre all afflictions here, to set at nought the vayne prosperitee of this worlde, and alway to longe for the euerlastinge felicitee: collected out of holy workes by the most vertuous and gracious princesse Katherine Queene of England, Fraunce, and Ireland. Place of Creation or Publ. (Hamnet): [London : Creator or Publisher (Hamnet): W. Powell?, Date of Creation or Publ. (Hamnet): ca. 1550] Physical Description (Hamnet): [62] p. ; 8⁰. Folger Holdings Notes (Hamnet): HH48/23. Brown goatskin binding, signed by W. Pratt. Imperfect: leaves D2-3 and all after D5 lacking; D2-3 and D6-7 supplied in pen facsimile. Pencilled bibliographical note of Bernard Quaritch. Provenance: Stainforth bookplate; Francis J. Stainforth - Harmsworth copy Notes (Hamnet): An edition of: Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions. Notes (Hamnet): D2r has an initial 'O' with a bird. Notes (Hamnet): Formerly STC 4821. Notes (Hamnet): Identified as STC 4821 on UMI microfilm, reel 678. Notes (Hamnet): Printer's name and publication date conjectured by STC. Notes (Hamnet): Running title reads: Praiers. Notes (Hamnet): Signatures: A-D⁸ (-D8). Notes (Hamnet): This edition has a prayer for King Edward towards the end. Citations (Hamnet): ESTC (RLIN) S114675 Citations (Hamnet): STC (2nd ed.), 4824a Subject (Hamnet): Prayers -- Early works to 1800. Associated Name (Hamnet): Harmsworth, R. Leicester Sir, (Robert Leicester), 1870-1937, former owner. Call Number (Hamnet): STC 4824a STC 4824a, title page not for reproduction without written permission. Folger Shakespeare Library 201 East Capitol Street, SE Washington, DC 20003](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/prayers-and-meditations.jpg?w=584) Folger Shakespeare Library

Folger Shakespeare LibraryPDI Record:

—

Call Number (PDI):

STC 4824a

Creator (PDI):

Catharine Parr, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1512-1548.

Title (PDI):

[Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions]

Created or Published (PDI):

[1550]

Physical Description (PDI):

title page

Image Root File (PDI):

17990

Image Type (PDI):

FSL collection

Image Record ID (PDI):

18050

MARC Bib 001 (PDI):

165567

Marc Holdings 001 (PDI):

159718

Hamnet Record:

—

Creator (Hamnet):

Catharine Parr, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1512-1548.

Uniform Title (Hamnet):

Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions

Title (Hamnet):

Praiers

Title (Hamnet):

Prayers or meditacions, wherein the minde is stirred, paciently to suffre all afflictions here, to set at nought the vayne prosperitee of this worlde, and alway to longe for the euerlastinge felicitee: collected out of holy workes by the most vertuous and gracious princesse Katherine Queene of England, Fraunce, and Ireland.

Place of Creation or Publ. (Hamnet):

[London :

Creator or Publisher (Hamnet):

W. Powell?,

Date of Creation or Publ. (Hamnet):

ca. 1550]

Physical Description (Hamnet):

[62] p. ; 8⁰.

Folger Holdings Notes (Hamnet):

HH48/23. Brown goatskin binding, signed by W. Pratt. Imperfect: leaves D2-3 and all after D5 lacking; D2-3 and D6-7 supplied in pen facsimile. Pencilled bibliographical note of Bernard Quaritch. Provenance: Stainforth bookplate; Francis J. Stainforth – Harmsworth copy

Notes (Hamnet):

An edition of: Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions.

Notes (Hamnet):

D2r has an initial ‘O’ with a bird.

Notes (Hamnet):

Formerly STC 4821.

Notes (Hamnet):

Identified as STC 4821 on UMI microfilm, reel 678.

Notes (Hamnet):

Printer’s name and publication date conjectured by STC.

Notes (Hamnet):

Running title reads: Praiers.

Notes (Hamnet):

Signatures: A-D⁸ (-D8).

Notes (Hamnet):

This edition has a prayer for King Edward towards the end.

Citations (Hamnet):

ESTC (RLIN) S114675

Citations (Hamnet):

STC (2nd ed.), 4824a

Subject (Hamnet):

Prayers — Early works to 1800.

Associated Name (Hamnet):

Harmsworth, R. Leicester Sir, (Robert Leicester), 1870-1937, former owner.

Call Number (Hamnet):

STC 4824a

STC 4824a, title page not for reproduction without written permission.

Folger Shakespeare Library

201 East Capitol Street, SE

Washington, DC 20003

Henry was said to be proud and at the same time jealous of his wife’s success. ‘Lamentations of a Sinner’ was not published until after Henry died [in 1547]. In ‘Lamentations‘, Catherine’s Protestant voice was a bit stronger. If she had published ‘Lamentations’ in Henry’s lifetime, she most likely would have been executed as a heretic despite her status as queen consort. Henry did not like his wives outshining him [i.e. Anne Boleyn]…hence her compliance and submission to the King when she found that she was to be arrested by the Catholic faction at court. Her voice may have been dialed down a notch, but once her step-son, the Protestant boy King Edward took the throne — she had nothing to hold her back. Her best friend, the Dowager Duchess of Suffolk, and brother Northampton encouraged Parr to publish.

A publication of the book The Lamentation of a Sinner c.1550 [after the death of Queen Katherine] from the book “Vivat Rex!: An Exhibition Commemorating the 500th Anniversary of the Accession of Henry VIII” by Arthur Schwarz

Published in 1547 [according to Sudeley Castle] after the death of King Henry VIII, “The Lamentation of a Sinner” was Katherine’s second book which was more extreme than her first publication. She was encouraged by her good friend the Duchess of Suffolk and her brother, the Marquess, to publish. The transcription of the title page here is… “The Lamentacion of a synner, made by the most vertuous Lady quene Caterine, bewailyng the ignoraunce of her blind life; let foorth & put in print at the inflance befire of the right gracious lady Caterine, Duchesse of Suffolke, and the ernest request of the right honourable Lord William Parre, Marquesse of Northampton.”

I was lucky enough to see a copy both a Sudeley Castle and at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. I am really interested in going to the Library and studying the actual book…one day!

Queen Katherine’s “Lamentations of a Sinner” on display at the Vivat Rex Exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Photo by Meg Mcgath (2009). See above for full description of the book the Folger has in their collection which can be seen in this photo.

Queen Katherine’s “Lamentations of a Sinner” on display at the Vivat Rex Exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Photo by Meg Mcgath (2009). See above for full description of the book the Folger has in their collection which can be seen in this photo.The Lamentation of a Sinner

Lamentations of a Sinner

by Catherine Parr, Queen of England and Ireland

“The Lamentacion of a synner, made by the most vertuous Lady quene Caterine, bewailyng the ignoraunce of her blind life; let foorth & put in print at the inflance befire of the right gracious lady Caterine, Duchesse of Suffolke, and the ernest request of the right honourable Lord William Parre, Marquesse of Northampton.”

Published in 1548 after the death of King Henry VIII, “The Lamentation of a Sinner” was Catherine’s second book which was more extreme than her first publication. She was encouraged by her good friend the Duchess of Suffolk and her brother, the Marquess, to publish.

[Vivat Rex Exhibition, Folger Shakespeare Library, STC 4828]

Family of Queen Katherine: Bess Throckmorton, Lady Raleigh

Abbie Cornish as Bess; lady to Elizabeth I in “Elizabeth: The Golden Age” (2007)

16 APRIL 1565: The BIRTH of Elizabeth “Bess” Throckmorton, Lady Raleigh (16 April 1565 – 1647) was a lady-in-waiting to Elizabeth I. Bess is said to have been intelligent, forthright, passionate and courageous. Elizabeth Throckmorton would have been a striking person in any age, including our own. She stands alongside Bess of Hardwick, a contemporary, and Lady Anne Clifford, a little later, as an example of the woman who overcomes all the considerable odds stacked against her.

“I envy you Bess. You’re free to have what I can’t have.”

Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007)

Family History at Court

Elizabeth’s family had deep rooted connections at court that started centuries before her birth. Elizabeth was the youngest child and only daughter of Sir Nicholas Throckmorton and his wife Anne Carew. Nicholas was the son of Sir George of Coughton Court and Katherine Vaux. The Throckmortons had been at court since the early reign of King Henry IV. Elizabeth’s great-great-grandfather, Sir Thomas Throckmorton, was High Sheriff of Warwick and Leicester counties during Henry’s reign. Nicholas’s mother, Katherine, just happened to be the uterine sister of Sir Thomas Parr, father of the future Queen Katherine. A uterine sibling meant that Sir Thomas and Lady Throckmorton shared the same mother, Elizabeth FitzHugh. Elizabeth was a daughter of Henry, Lord FitzHugh and Lady Alice [born Neville]. As the daughter of a Neville, there is no need to explain the Neville connections to the crown. I will simply note that they were descended from the Beaufort children of Prince John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and his third wife, Katherine Swynford. Elizabeth FitzHugh was at court as Lady Parr until her husband died in 1483. Sir William Parr was a staunch supporter of the House of York and had been a close confidant of King Edward IV. However, once the Duke of Gloucester took the throne as Richard III, Parr declined any involvement in Richard’s coronation and reign. Lord Parr headed north where he died shortly after. His widow, Elizabeth, would marry again sometime before or shortly after Henry Tudor took the throne as King Henry VII. The new husband was a staunch Lancastrian. Nicholas Vaux’s mother had served Margaret of Anjou. Nicholas was a protege of Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of the new King. And this, my friends, was how it was played at court. Alignment with the right people and monarch on the throne made life comfortable for everyone involved. Elizabeth, now Lady Vaux, had three daughters by her second husband, Nicholas [later Baron Vaux of Harrowden].

Family

Elizabeth Throckmorton’s father, Lord Nicholas, later a diplomat, served in the household of Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond as a page. The position is thought to have been attained by his uncle, Sir William Parr [later Baron Parr of Horton], in 1532. Sir William had been appointed Chamberlain of the household of the illegitimate son of King Henry VIII. Nicholas’s cousin, also named William, was present in Richmond’s household as a companion. William learned and played alongside Richmond and another companion, the Earl of Surrey [Henry Howard]. Nicholas ventured with Fitzroy as he traveled to France to meet King Francis. He stayed on for about a year and became somewhat fluent in French. After Fitzroy’s death in 1536, Nicholas’s options were somewhat limited. His mother, Katherine, used her influence as an aunt to obtain him a position in the household of his cousin, Lord William Parr [created Earl of Essex in December 1543]. In July 1543, his cousin Katherine Parr, was married to King Henry VIII as his sixth queen. By 1544-47 or 8, Nicholas had been appointed to the Queen’s household as a sewer. Nicholas would go on to serve under the rest of the Tudor monarchs; Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I.

Nicholas Throckmorton and his wife, Anne Carew.

Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Carew, was the daughter of Sir Nicholas Carew and Elizabeth Bryan. Lady Bryan married Sir Thomas Bryan and was governess to all three of Henry VIII’s children at one point in time. Lady Bryan was the daughter of Elizabeth Tilney by her first marriage to Sir Humphrey Bourchier. By her mother’s second marriage to Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey [later Duke of Norfolk], Lady Bryan was an aunt of Queen Anne Boleyn and Queen Katherine Howard. Anne Carew’s father, Nicholas, was a grandson of Eleanor Hoo. Eleanor was sister to Sir Thomas Boleyn’s [father of Queen Anne Boleyn] grandmother, Anne Hoo. Courtiers, by this time, had started to close the gap between the affinity to each other, meaning most of the court was related to each other. One way or another.

Life

Elizabeth was only six when her father died. In 1584, she went to court and became a lady-in-waiting to the Queen. She eventually became a gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber (she dressed and undressed Elizabeth).

Sir Walter Raleigh was in favour with Queen Elizabeth until he fell in love with the daughter of Sir Nicholas Throckmorton. Look AND Learn History Picture Library.

In 1590, she caught the eye of Sir Walter Raleigh, a rising royal favorite. In November 1591, the couple secretly wed after Elizabeth discovered she was pregnant. For months, Elizabeth kept her secret from the queen and withdrew to her brother’s house in London, where she gave birth to a son in March 1592. The queen came to discover what had happened and both Elizabeth and Raleigh were thrown in to The Tower of London.

In December 1592, after Elizabeth had lost her child, the two were released, but Raleigh was refused to be seen by the queen for a year and the queen never forgave Lady Raleigh. In 1601, an attempt to restore her at court failed. Lady Raleigh spent most of her time at Sherborne, their country home in Dorset. In 1593, Lady Raleigh gave birth to another son named Walter at Sherborne. Lady Raleigh did come and go between London, but much of the 1590s saw husband and wife separated from each other.

Sir Walter Raleigh lead an exhibition to the Orinoco basin to South America in 1595; while in 1596, Raleigh was made a leader of the Cadiz Raid.

After the ascension of James I in 1603, Raleigh’s enemies at court convinced King James that he was a threat and Raleigh was imprisoned again in the Tower.

In 1605, Lady Raleigh gave birth to another son named Carew either in or around the Tower. In 1609, the King confiscated Sherborne and Lady Raleigh was given a small pension to live off of.

Lady Raleigh lived with her husband until 1610. Despite her many appeals, her husband was executed on 29 October 1618. Lady Raleigh ended up keeping her husband’s head which she had embalmed. It is said that she carried the head with her until her own death. Whether that’s true, who knows!

Bess would go on to rebuild her life after the death of her husband. She was perused by creditors for the rest of her life but in time came to clear her family’s name. She earned back her fortunes and prospects and ended up a rich widow in time. Bess became good friend to John Donne and Ben Jonson [the play write], and mother of an MP.

MEDIA

Elizabeth “Bess” Throckmorton portrayals through out the years in film.

- The Virgin Queen (1955): Sir Walter Raleigh gains audience with Queen Elizabeth I seeking her support – and money for ships to sail – but soon finds himself caught between the Queen’s desire for him and his love for Beth Throgmorton (Joan Collins). Ben Nye was makeup artist.

- Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007): This sequel to Elizabeth deals with Elizabeth’s handling of the Spanish Armada, and the problem of Mary Queen of Scots, while infatuated with sir Walter Raleigh. The Armada is dealt with in short order, Mary with much anguish but thanks to Bess Throckmorton (Abbie Cornish) Raleigh slips from her grasp. Jenny Shircore was hair & makeup designer.

- The Simpsons (2009): The plot of this one was basically The Simpsons’ take on “Elizabeth: The Golden Age” with Selma as Elizabeth I, Homer as Sir Walter Raleigh, and Marge as Bess Throckmorton. (Eakins)

- “My Just Desire : The Life of Bess Raleigh, Wife to Sir Walter” by Anne Beer.

- Rebecca Larson. Elizabeth “Bess” Throckmorton: The Queen’s Permission, The Tudor Dynasty, 15 August 2016. URL: http://www.tudorsdynasty.com/elizabeth-bess-throckmorton-raleigh/

Sources

- John A. Wagner, Susan Walters Schmid Ph. D. Encyclopedia of Tudor England, ABC-CLIO, Dec 31, 2011. pg 920-21.

- Geoffrey Moorhouse. Blessed Bess, The Guardian, Friday 20 February 2004.

- Laura Eakins. More Fun with Screen Captures, 6 June 2009.

- The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558: THROCKMORTON, Nicholas (1515/16-71), of London and Paulerspury, Northants., ed. S.T. Bindoff, 1982

- The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558: THROCKMORTON, Sir George (by 1489-1552), of Coughton, Warws., ed. S.T. Bindoff, 1982

Sudeley Castle History: Ralph Boteler, 1st Baron Sudeley

Boteler of Sudeley coat of arms; bore gules, a fess countercompony argent and sablo between six crosses pattee or

Family

Ralph Boteler was the youngest surviving son of Sir Thomas Boteler, de jure 4th Baron of Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire and Alice Beauchamp (d. 1443), daughter of Sir John Beauchamp of Powick, Worcestershire.[1]

His paternal grandparents were Sir William le Boteler, 2nd Baron Boteler and co-heiress Joan de Sudeley, daughter of John de Sudeley, 2nd Baron Sudeley.

Life

Boteler was a military commander and member of the King’s Household under both Henry V and Henry VI. In 1418, Boteler was part of the retinue of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (son of Henry IV) on the occasion of Henry V’s visit to Troyes.[6] He was present for the signing of the Treaty of Troyes which agreed that after the death of Charles VI of France, his heirs male would inherit the throne of France.[6] The treaty also required that Henry espouse the Princess Katherine of Valois, a younger daughter of Charles VI and sister to Isabella of Valois, the second queen to Richard II of England.[6] In 1420-21, Boteler was awarded grants of land in France most likely for his service to the King. After the signing of the treaty, Boteler was part of the attack against the Dauphin of France to keep him from trying to reclaim his right to the succession.

Dugdale quotes, “he was retained by indenture to serve the King in his wars of France with twenty men-at-arms and sixty archers on horseback.” (Dent)

Again, “In the beginning of the following reign, he had liscence to travel beyond the sea; was again in the wars of France and of the retinue of John, Duke of Bedford (brother of Henry V).” (Dent)

The Duke of Bedford was named Protector of the Realm and carried on the wars of France. Dent states that after the fall of Joan of Arc, Boteler rejoined Bedford at Rouen and was present for her burning at the stake.

He was made a Knight of the Garter in 1420.[4] He was captain of Arques and Crotoy in 1423 and took muster in Calais in 1425.[3] In 1441, Boteler became Lord Chamberlain of the King’s household.[6] The following year, Boteler was made Treasurer of the King’s Exchequer.[6] He was then sent as an ambassador with Richard, Duke of York, to negotiate a treaty with France. He served as Lord High Treasurer of England from 1443 to 1446. In 1447, he was associated with John, Viscount Beaumont in the Governorship of the “Isle of Jersey, Garnesey, Serke, and Erme” with the priories-alien and all their possessions in those islands; to hold during the minority of Anne, daughter and heiress of Henry Beauchamp, 1st Duke of Warwick (husband to Lady Cecily Neville, sister to Lady Alice, great-grandmother of Queen Katherine Parr).[6] The employment was short as the young heiress died in 1449. Boteler then joined commission with James Butler, Earl of Wiltshire, in the Governorship of the town, marches, and castle of Calais.

In 1458, Boteler was acknowledged for his great service done to King Henry V and Henry VI in France and Normandy. Upon the fall of Henry VI, things drastically turned. Boteler excused himself from Parliament due to his age. He then devoted himself to the re-construction of Sudeley Castle.

View of the back of Sudeley Castle in Gloucestershire showing the landscape it overlooks. Sudeley is one of the grandest late medieval houses in Gloucestershire. Many of the buildings are ruined but the long medieval hall appears habitable. The Castle Chapel is striking, very much in the Gothic Perpendicular style with heavily pinnacled roof. It has a Royal connection, as Katherine Parr, the last Queen of Henry VIII died here in 1548 and was buried in this Chapel. The large rear window of the chapel is obscured by foliage, which suggests that the Chapel was at this date in a bad state of repair. Between 1554 and 1813, it was held by the Chandos family, although it was damaged during the Civil War, which made it largely inhabitable.

Boteler was a huge benefactor to the churches. He erected St. Mary’s Chapel and aided the parishioners of Winchcombe to restore their Parish Church.[6]

In May 1455, Boteler took up arms again for the King at the first Battle of St. Alban’s. The First Battle of St Albans, fought on 22 May 1455 at St Albans, 22 miles (35 km) north of London, traditionally marks the beginning of the Wars of the Roses. Richard, Duke of York (husband to Lady Cecily Neville and father to Edward IV and Richard III) and his ally, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (Warwick, the Kingmaker, uncle to Elizabeth Parr, grandmother of Queen Katherine), defeated the Lancastrians under Edmund, Duke of Somerset, who was killed. York captured Henry VI.[6]When Edward IV took the throne, things turned for the bad for Boteler. Boteler was forced to give up Sudeley Castle — Edward was depriving the Lancastrians of their lands, etc. leaving some of them in poverty while the Yorks’ flourished with the new grants that had been transferred from the Lancastrians to them. Records show Boteler reluctantly handing over the Castle. It states that he confirmed the Castle over to Richard, Earl of Rivers; William, Earl of Pembroke; Antony Wydville; Lord Scales; William Hastings; Lord Hastings; Thomas Bonyfaunt, Dean of the Chapel Royal; Thomas Vaughan; and Richard Fowler.[6] With this went the inheritance of his heirs as well.

When the Lancastrian party rose again in 1470, there was hope that Sudeley would be restored to Boteler, but the House of York refused. The Castle was handed over to the Earl of Rivers and the others named above, but it was not meant to stay with them. Instead, Edward IV granted the Castle to his brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester (later King Richard III).[6] It would remain Crown property until a grant to Thomas, Lord Seymour, the husband of Queen Katherine Parr, widow of King Henry VIII, in 1547 by his nephew King Edward VI (son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, wife 3). Shortly after Sudeley was taken from Lord Seymour, the Castle would temporarily pass to the late Queen’s brother, Marquess of Northampton (Sir William Parr) until the accession of Queen Mary I.

Lord Sudeley

Tree of the Lords of Sudeley from “Annals of Winchcombe and Sudeley” by Emma Dent, Lady Sudeley, 1877.

Ralph inherited Sudeley Castle from his mother; he started rebuilding in 1442.[4][6] Unfortunately he failed to gain royal permission to crenellate it and had to seek Henry VI’s pardon.[5] Boteler was a supporter of the House of Lancaster during the War of the Roses. In 1469, Boteler was forced to sell Sudeley to King Edward IV due to his support for the Lancastrian cause. Sudeley became Royal property.

Marriage and Family

Lord Sudeley married twice. Before 6 July 1419, he married commercial wealth, in the person of Elizabeth Norbury, widow of John Hende (d. 1418), late Mayor of London, and daughter of John Norbury.[1] They had two sons, Ralph and Thomas, Knt.[1] She died 28 August 1462, and in the following year he married Alice (d. 1474), daughter of John, Baron Deyncourt, and widow of William, Baron Lovel of Titchmarsh, Northamptonshire, who survived him.[1] They had no issue.[1]

Sudeley’s only surviving son from his first marriage, Thomas, predeceased him, also without a male heir.[1] Thomas’ widow Eleanor was the Lady Eleanor Boteler[7] (known as the Holy Harlot) whose alleged pre-contract of marriage to Edward IV of England was claimed to have invalidated Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, and so legitimized the usurpation of Richard III of England. Lady Eleanor describes herself as “lately the wife of Thomas Boteler, knight, now deceased.”[7]

References

- Douglas Richardson. Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study In Colonial And Medieval Families, 2nd Edition, 2011. pg 230-32.

- John Ashdown-Hill, “Eleanor The Secret Queen“, The History Press, 2009, pg 50 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- John Ashdown-Hill, “Eleanor The Secret Queen“, The History Press, 2009. pg 52 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- Sudeley Castle Online: History Timeline URL: http://www.sudeleycastle.co.uk/history

- John Ashdown-Hill, “Eleanor The Secret Queen“, The History Press, 2009. pg 51 ISBN 978-0-7524-5669-0

- Emma Dent. ”Annals of Winchcombe and Sudeley,” J. Murray, 1877.

- John Ashdown-Hill, “Eleanor The Secret Queen”, The History Press, 2009. pg 140

12 FEBRUARY: The Throckmorton Brothers

The Throckmorton family of Coughton Court in Warwickshire is one of the oldest Catholic families in England. The Throckmortons were prominent in the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I (Tudor). Sir George Throckmorton was a favorite of King Henry VIII during his early years as King. He owed his position probably due to his brother-in-law, Sir Thomas Parr, comptroller of the King’s household and loyal friend of the King. However, his marriage to the Lancastrian Vaux family may have had something to do it. Throckmorton’s wife, Lady Katherine (Vaux), was the younger half-sister of Lord Parr, both being children from one of Lady Elizabeth’s (born FitzHugh) two marriages; Lord Parr and Lord Vaux. The Vaux family was loyal to Henry VI and especially Margaret of Anjou when she was exiled to France. George’s father-in-law, Nicholas, became a protege and favorite of Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII Tudor. As the stepson of Lord Vaux (Lord William Parr died shortly after the coronation of Richard III in 1483), Thomas Parr is noted to have been a possible pupil in the household of Henry VIII’s grandmother as a young lad.

The connection to the Parr family made Throckmorton an uncle by marriage to queen consort Katherine Parr, the Marquess of Northampton, and Lady Anne Herbert (wife of William, 1st Earl of Pembroke). The Parrs also shared common ancestry with the Throckmorton’s through their maternal great-grandmother Matilda Throckmorton (Lady Green), daughter of Sir John Throckmorton and Eleanor de la Spiney (great-grandparents of Sir George). George Throckmorton, however, would become involved in a scandal to keep the King from divorcing his first wife, Queen Katherine of Aragon, to marry her lady-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn. Throckmorton didn’t approve and supported the queen. Most members, including Sir Thomas Parr’s widow and his cousin, Lady Maud Parr (Green), stuck by Katherine of Aragon until her household was dissolved.

12 FEBRUARY 1570: THE DEATH of Sir Nicholas Throckmorton

Sir Nicholas Throckmorton by Unknown Anglo-Netherlandish artist. © National Portrait Gallery, London

A cousin of Katherine Parr, Throckmorton was a staunch Protestant, and a supporter of Lady Jane Grey, though he served as a Member of Parliament under all the Tudor monarchs including the Catholic queen, Mary I. His importance during the reign of Elizabeth I was mainly as an ambassador to France and to Scotland. Throckmorton was the son of Katherine’s paternal aunt, Hon. Katherine Vaux and cousin Sir Robert Throckmorton of Coughton Court (a supporter of Queen Katherine of Aragon). Throckmorton was a page in the household of Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond by 1532-6; his cousin, William Parr (brother of Queen Katherine) had been raised and educated with Fitzroy and the Earl of Surrey and his maternal uncle, also named William Parr, was head of the household there. Throckmorton then became a servant in the household of his cousin, William, Baron Parr by 1543. Throckmorton, along with his brother Clement, would go on to serve in the household of their cousin Queen Katherine Parr by 1544-7 or 8. After the reign of Henry VIII, Throckmorton continued to serve at court. Upon the death of the Dowager Queen, he returned to the household of his cousin, the 1st Marquess of Northampton (William Parr).

12 FEBRUARY 1581: THE DEATH of Sir Robert Throckmorton

Robert Throckmorton by British School (c) National Trust, Coughton Court; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

Sir Robert Throckmorton (c.1513-12 February 1581) was the eldest son of Sir George Throckmorton of Coughton Court and Hon. Katherine Vaux. As such, Robert was the elder brother of Nicholas, above. Throckmorton, like his father, was Catholic. His role in the succession crisis of Queen Mary is not clear, but it seems that he backed Mary’s claim because of the positions he was given. He was knighted in 1553 and appointed Constable of Warwick Castle among other positions. His Catholicism explains his disappearance from the Commons in the reign of Elizabeth I, although the most Catholic of his brothers, Anthony Throckmorton, was to sit in the Parliament of 1563. Judged an ‘adversary of true religion’ in 1564, Throckmorton remained active in Warwickshire until his refusal to subscribe to the Act of Uniformity led to his removal from the commission of the peace. (A. L. Rowse) Throckmorton married twice and had issue by both wives who would continue his legacy at Coughton Court.

References

- S.T. Bindoff. “The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558,” 1982: THROCKMORTON, Sir Nicholas (1515/16-71), of Aldgate, London and Paulerspury, Northants.

- S.T. Bindoff. “The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558,” 1982: THROCKMORTON, Robert (by 1513-81), of Coughton, Warws. and Weston Underwood, Bucks.

- Peter Marshall, David Starkey. “Catholic Gentry in English Society: The Throckmortons of Coughton from Reformation to Emancipation,” Intro by David Starkey, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., Nov 17, 2009.

20 JANUARY 1569: THE DEATH of Myles Coverdale

Stained glass at St. Mary’s, Sudeley Castle (where Queen Catherine is buried). The window depicts Myles Coverdale (L) with Lady Jane Grey (C) and John Brydges, 1st Baron Chandos (R).

20 JANUARY 1569: THE DEATH of Myles Coverdale, Bishop of Exeter. Coverdale assisted William Tyndale in the complete version of the Bible, printed probably at Hamburgh in 1535. After the death of King Henry, Coverdale became the Dowager Queen’s personal almoner. He assisted her in her endeavours to popularise Erasmus’ works. He preached her funeral sermon in September 1548. Coverdale died in London and was buried in the church of St. Bartholomew. When that church was demolished in 1840 to make way for the new Royal Exchange, his remains were moved to St. Magnus.

![Tomb of Sir George and his wife Katherine [Vaux] in St. Peter's Church, Coughton Court, Warwickshire, England.](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/1-b.jpg?w=584)

![A publication of the book c.1550 [after the death of Queen Katherine]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/img_4646.png?w=584&h=886)