Lady Anne Devereux, Countess of Pembroke

© Meg McGath 24 January 2015

Pembroke Castle which was taken over from Jasper Tudor [uncle of the future King Henry VII], Earl of Pembroke. The castle and Tudor’s title was then given to the Yorkist supporter, Sir William Herbert. Anne Devereux would have spent time here while she was married.

(c. 1430,

Bodenham

– after June 25, 1486), was a daughter of a Yorkist Knight. By her marriage to Sir William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke and Baron Herbert, Anne became a leading noblewoman in Wales.

Family

Anne was the daughter of Sir Walter Devereux, the Lord Chancellor of Ireland, and his wife Elizabeth Merbury.[1] Lord Devereux and his son-in-law, Lord Herbert, were responsible for the capture of Sir Edmund Tudor [father to the future King Henry VII]. Tudor was a half-brother to the Lancastrian King Henry VI by his mother’s second marriage to Owen Tudor.

Anne was the daughter of Sir Walter Devereux, the Lord Chancellor of Ireland, and his wife Elizabeth Merbury.[1] Lord Devereux and his son-in-law, Lord Herbert, were responsible for the capture of Sir Edmund Tudor [father to the future King Henry VII]. Tudor was a half-brother to the Lancastrian King Henry VI by his mother’s second marriage to Owen Tudor.

Anne had two siblings, Walter and John. Walter was knighted after the Battle of Towton on 29 March 1461 by the Yorkist King Edward IV. By right of his wife, the heiress Lady Anne, 7th Baroness Ferrers of Chartley, he was raised to Baron Ferrers of Chartley on 26 July 1461. Lord Walter held various positions during the ruling of the House of York [Kings Edward IV, Edward V, and Richard III] but was ultimately killed in the last battle of the War of the Roses, the Battle of Bosworth 22 August 1485. He was succeeded by his son and heir, John, who became the 8th Baron Ferrers of Chartley. The 8th Baron would marry Lady Cecily Bourchier [her paternal grandparents were both descendants of King Edward III. Cecily was also a niece of queen consort Elizabeth Woodville by Cecily’s mother, Anne]. The couple were 2nd great-grandparents to Sir Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex who was a favorite of Queen Regnant Elizabeth I [daughter of King Henry VIII of the House of Tudor].[8][9][10]

The Crophull Inheritance

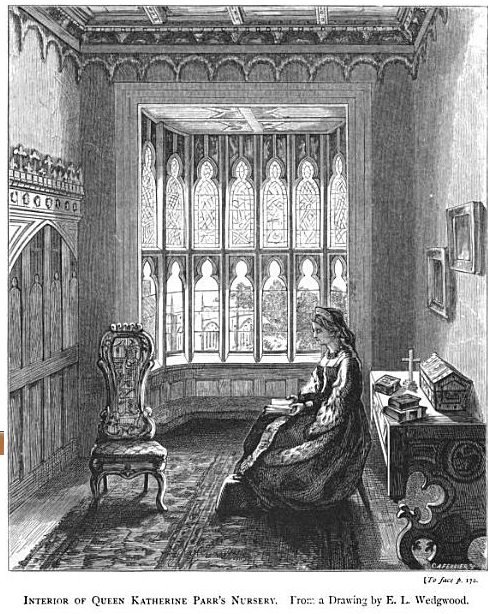

Anne’s grandfather, Walter, was the son of Agnes Crophull. By Crophull’s second marriage to Sir John Parr, Anne was a cousin to the Parr family which included Sir Thomas Parr; father of King Henry VIII’s last queen consort, Katherine Parr.[2][3][4]

Tomb of Agnes Crophull and her third husband, Sir John Merbury. Weobley, Herefordshire, England.

Anne’s great-grandmother was a great heiress of her father. She was married firstly to Sir Walter Devereux [died 1402] while she was still underage. Upon Agnes’s coming of age in September 1385, Devereux seized the remaining estates based on his marriage right in 1386.[7] These included Weobley manor (Herefordshire); Sutton Bonnington manor and lands at Arnold (Nottinghamshire); the manors of Cotesbach, Braunston, and Hemington (Leicestershire); and an estate at Market Rasen (Lincolnshire). Weobley would become his principal residence.

When Agnes Crophull died on 9 Feb 1436, Crophull’s heir was Anne Devereux’s father, Sir Walter Devereux [grandson of Crophull]. Estates like Lyonshall passed to Walter from Agnes, and also by right of his wife, Elizabeth Merbury, who was the daughter [step-daughter of Agnes] of Agnes Crophull’s third husband, John Merbury, by a previous marriage. Merbury and Agnes were buried together in Weobley’s Parish of St. Peter and St. Paul. Anne’s great-grandfather, Walter [first husband to Agnes Crophull], is also supposedly buried there in a separate tomb. Through her father, Anne was a descendant of King Henry II and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine by their children John, King of England and Eleanor of England, Queen of Castile.[1]

Marriage

About 1445, Anne married Sir William Herbert, [later 1st Earl of Pembroke], in Herefordshire, England. He was the second son of Sir William ap Thomas of Raglan, a member of the Welsh Gentry Family, and his second wife Gwladys ferch Dafydd Gam.[1]

The arms of Lord William Herbert, K.B.

Sir William Herbert was a very ambitious man. During the War of the Roses, Wales heavily supported the Lancastrian cause. Jasper Tudor, 1st Earl of Pembroke and other Lancastrians remained in control of fortresses at Pembroke, Harlech, Carreg Cennen, and Denbigh. On 8 May 1461, as a loyal supporter of King Edward IV, Herbert was appointed Life Chamberlain of South Wales and steward of Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire. King Edward’s appointment signaled his intention to make replace Jasper Tudor with Herbert who would become the premier nobleman in Wales. Herbert was created Lord Herbert on 26 July 1461. Herbert was then ordered to seize the county and title of Earl of Pembroke from Jasper Tudor. On 29 March 1461, Lord Herbert became the 1st Earl of Pembroke. By the end of August, Herbert had taken back control of Wales with the well fortified Pembroke Castle capitulating on 30 September 1461. With this victory for the House of York came the inmate at Pembroke; the five year old nephew of Jasper Tudor, Henry, Earl of Richmond. Determined to enhance his power and arrange good marriages for his daughters, in March 1462 he paid 1,000 for the wardship of Henry Tudor. Herbert planned a marriage between Tudor and his eldest daughter, Maud. At the same time, Herbert secured the young Henry Percy who had just inherited the title of Earl of Northumberland. Herbert’s court at Raglan Castle was where young Henry Tudor would spend his childhood, under the supervision of Herbert’s wife, Anne Devereux. While at Raglan Castle, Anne must have understood the importance of the potential marriage between her daughter and Henry Tudor. Therefore, Anne insured that young Henry was well cared for.[5]

Detail of a miniature of a king enthroned surrounded by courtiers with Sir William Herbert and his wife, Anne Devereux kneeling before him, wearing clothes decorated with their coats of arms, from John Lydgate’s Troy Book and Siege of Thebes, with verses by William Cornish, John Skelton, William Peeris and others, England, c. 1457 (with later additions), Royal 18 D. ii, f. 6. © British Library, 2015.

In the Battle of Edgecote on 26 July 1469, the Yorkists, led by Pembroke, were defeated by the Lancastrians. The Lancastrians were lead by Sir Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick; the man who helped Edward, Earl of March become King Edward IV.[a] Warwick had decided to fight against his cousin Edward and restored the Lancastrian King Henry VI for a few years while Edward went into exile. After the battle, the Earl of Pembroke and his brother Richard were executed near Banbury by the Lancastrians. Henry Tudor was lead from the battlefield to the home of Pembroke’s brother-in-law, Lord Ferrers, at Weobley in Herefordshire. It was there that Sir Reginald Bray, a servant of Henry Tudor’s mother Lady Margaret Beaufort, found Tudor six days after the battle. Anne, now Dowager Countess of Pembroke, was found sheltered by Lord Ferrers where she continued to look after Henry Tudor.[5]

Issue

The Earl and Countess of Pembroke had three sons and seven daughters:[1]

- Sir William Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, Earl of Huntingdon[1], married firstly to Mary Woodville; daughter of Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers and thus sister to King Edward IV’s queen consort Elizabeth Woodville. He married secondly to Lady Katherine Plantagenet, the illegitimate daughter of King Richard III.[1] [b]

- Sir Walter Herbert[1]

- Sir George Herbert[1]

- Lady Maud Herbert, wife of Sir Henry Percy, 4th Earl of Northumberland, 7th Lord Percy.[1]

- Lady Katherine Herbert, wife of Sir George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent.[1]

- Lady Anne Herbert, wife of Sir John Grey, 1st Baron Grey of Powis.[1]

- Lady Margaret Herbert, wife of Sir Thomas Talbot, 2nd Viscount Lisle, and of Sir Walter Bodrugan.[1]

- Lady Cecily Herbert, wife of John Greystoke.[1]

- Lady Elizabeth Herbert, wife of Sir Thomas Cokesey.[1]

- Lady Crisli Herbert, wife of Mr. Cornwall.[1]

Sadly, the earldom did not pass down through his son, the 2nd Earl of Pembroke. The 2nd Earl’s only child by Mary Woodville was a daughter, Lady Elizabeth Herbert. Lady Elizabeth became Baroness Herbert in her own right. As a woman, Lady Herbert could not inherit the Earldom of Pembroke. She did receive extensive lands in Wales.[c]

The Earl of Pembroke also fathered several children by various mistresses.[1]

- Sir Richard Herbert of Ewyas, Herefordshire was the illegitimate son of William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke and most likely Maud, daughter of Adam ap Howell Graunt (Gwynn). Their son, William, would be created Earl of Pembroke [of the tenth creation] on 11 October 1551 by King Edward VI [son of King Henry VIII]. This brought the Earldom back into the Herbert family where it remains to this day. Pembroke was lucky enough to marry to Anne Parr.[d]

- Sir George Herbert. The son of Frond verch Hoesgyn. Married Sybil Croft.[2]

- Sir William Herbert of Troye. Son of Frond verch Hoesgyn. Married, second, Blanche Whitney (née Milborne) see Blanche Herbert, Lady Troy. They had two sons.[6]

After the death of her husband, the Dowager Countess was recorded as still living after 25 June 1486. She most likely died soon after.

Notes

[a] Lord Warwick was the son of Sir Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury and Lady Alice, Countess of Salisbury [in her own right]. Salisbury and his siblings by Lady Joan Beaufort was a grandson of Prince John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and Titular King of Castile [son of King Edward III]. One of Salisbury’s siblings was none other then Lady Cecily [Duchess of York] who would marry to the Yorkist rival, Richard, 3rd Duke of York. The couple were parents to both Kings Edward IV and Richard III. Lord Warwick’s siblings included Lady Alice FitzHugh [born Neville] who was mother to Lady Elizabeth Parr; the second husband of Sir William Parr, Baron Parr of Kendal. The two were grandparents to queen consort of Henry VIII [great-grandson of the Duke and Duchess of York], Katherine Parr.

[b] Lady Herbert married to Lord Charles Somerset, Earl of Worcester, a legitimized son of Lord Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of Worcester. The 3rd Duke was a son of Lord Edmund, 2nd Duke and Lady Elizabeth Beauchamp. Both parents had royal and noble descent. The 2nd Duke was from the legitimized line, the Beauforts, who were children of Prince John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster. Elizabeth Beauchamp was the daughter of the 13th Earl of Warwick who was the father of Lady Anne Beauchamp who became the 16th Countess of Warwick in her own right after the death of her brother. Her title was inherited by her husband, the infamous “Warwick, the Kingmaker” [Sir Richard Neville,16th Earl of Warwick].

[c] In 1479, the Earldom was bestowed upon Prince Edward of York, later King Edward V [Plantagenet]. When the King went missing after being lodged in The Tower of London, the Earldom merged into the crown. It was restored under the new King, Henry Tudor, who became Henry VII of England. An interesting turn of events was in 1532. Henry VII’s son, Henry VIII decided to grant the title to Anne Boleyn as ‘Marquess of Pembroke’ two months before their marriage to elevate her status. Anne Boleyn had been lady-in-waiting to Henry VIII’s first wife, Queen Katherine of Aragon. A romance blossomed between the two despite her position as the daughter of a knight. They were eventually married under the “new religion” that made Henry VIII Supreme Head of the Church of England. The Catholic Church never granted an annulment from his first marriage and never recognized the marriage of Henry and Anne. Anne was crowned queen and gave birth to a daughter, Elizabeth [later queen]. After failing to produce a son, Anne had charges brought up against her that eventually led to her execution. Coincidentally, her own lady-in-waiting Jane Seymour, took Anne’s place as the next wife and queen consort. Queen Jane did give birth to a son, Edward [later King].

[d] Herbert married to Anne Parr, daughter of Sir Thomas [a courtier and favorite of King Henry VIII] and Lady Maud Parr [Green]. At the time, it was a step up for Herbert as Anne was descended from a great lineage. It has been said, that because of his marriage to Anne, it brought some legitimacy to the Herbert family. In 1543, Herbert’s sister-in-law, the Dowager Lady Katherine Latimer [widow of Sir John Neville, 3rd Baron Latimer of Snape], would become the sixth and final queen consort to King Henry VIII. Both Lord and Lady Herbert were present at the ceremony. The marriage only brought on more advancement for Herbert and his family. After the death of King Henry VIII in 1547, Herbert became one of the guardians of the young King Edward VI. He was made a Knight of the Garter in 1549, and created Baron Herbert of Cardiff on 10 October 1551, and 1st Earl of Pembroke of the [tenth creation] the following day.

References

- :a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Douglas Richardson. Plantagenet Ancestry, 2nd Edition, 2011. pg 249.

- Douglas Richardson. Magna Carta Ancestry, 2nd Edition, Vol. II, pg 2.

- Douglas Richardson. Magna Carta Ancestry, 2nd Edition, Vol. III, pg 297-298.

- Douglas Richardson. Royal Ancestry, Vol. V, pg 248.

- Chris Skidmore. The Rise of the Tudors: The Family That Changed English History, Macmillian, 14 January 2014. pg 47.

- Ruth E. Richardson. Mistress Blanche: Queen Elizabeth I’s Confidante, Logaston Press. 1 November 2007.

- Calendar of Close Rolls, Richard II, Volume 3. H.C. Maxwell Lyte (editor). 1921. pages 32 to 35, 27 September 1385, Westminster.

- Douglas Richardson. Plantagenet Ancestry, 2nd Edition, 2011. pg 607-8.

- Douglas Richardson. Plantagenet Ancestry, 2nd Edition, 2011. pg 45-6.

- Charles Mosley (editor). Burke’s Peerage & Baronetage, 106th Edition. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1999. Volume 1, pages1378-80

Written and Researched by Ms. McGath

© Meg McGath 24 January 2015

All Rights Reserved

![Tomb of Sir George and his wife Katherine [Vaux] in St. Peter's Church, Coughton Court, Warwickshire, England.](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/1-b.jpg?w=584)

![Effigy of the Earl of Derby and Lady Stanley [Lady Eleanor Neville].](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/thomas-stanley_and_effigy_of_eleanor_neville.jpg?w=584&h=439)

![Folger Shakespeare Library PDI Record: --- Call Number (PDI): STC 4824a Creator (PDI): Catharine Parr, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1512-1548. Title (PDI): [Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions] Created or Published (PDI): [1550] Physical Description (PDI): title page Image Root File (PDI): 17990 Image Type (PDI): FSL collection Image Record ID (PDI): 18050 MARC Bib 001 (PDI): 165567 Marc Holdings 001 (PDI): 159718 Hamnet Record: --- Creator (Hamnet): Catharine Parr, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1512-1548. Uniform Title (Hamnet): Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions Title (Hamnet): Praiers Title (Hamnet): Prayers or meditacions, wherein the minde is stirred, paciently to suffre all afflictions here, to set at nought the vayne prosperitee of this worlde, and alway to longe for the euerlastinge felicitee: collected out of holy workes by the most vertuous and gracious princesse Katherine Queene of England, Fraunce, and Ireland. Place of Creation or Publ. (Hamnet): [London : Creator or Publisher (Hamnet): W. Powell?, Date of Creation or Publ. (Hamnet): ca. 1550] Physical Description (Hamnet): [62] p. ; 8⁰. Folger Holdings Notes (Hamnet): HH48/23. Brown goatskin binding, signed by W. Pratt. Imperfect: leaves D2-3 and all after D5 lacking; D2-3 and D6-7 supplied in pen facsimile. Pencilled bibliographical note of Bernard Quaritch. Provenance: Stainforth bookplate; Francis J. Stainforth - Harmsworth copy Notes (Hamnet): An edition of: Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions. Notes (Hamnet): D2r has an initial 'O' with a bird. Notes (Hamnet): Formerly STC 4821. Notes (Hamnet): Identified as STC 4821 on UMI microfilm, reel 678. Notes (Hamnet): Printer's name and publication date conjectured by STC. Notes (Hamnet): Running title reads: Praiers. Notes (Hamnet): Signatures: A-D⁸ (-D8). Notes (Hamnet): This edition has a prayer for King Edward towards the end. Citations (Hamnet): ESTC (RLIN) S114675 Citations (Hamnet): STC (2nd ed.), 4824a Subject (Hamnet): Prayers -- Early works to 1800. Associated Name (Hamnet): Harmsworth, R. Leicester Sir, (Robert Leicester), 1870-1937, former owner. Call Number (Hamnet): STC 4824a STC 4824a, title page not for reproduction without written permission. Folger Shakespeare Library 201 East Capitol Street, SE Washington, DC 20003](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/prayers-and-meditations.jpg?w=584)