Lady Alice Neville (c. 1430 – after 22 November 1503), Baroness (Lady) FitzHugh of Ravensworth, was an English noblewoman and part of the great noble Neville family. She was the daughter of Sir Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury and his wife, Lady Alice Montacute, suo jure 5th Countess of Salisbury. Alice became Lady FitzHugh upon her marriage to Sir Henry FitzHugh, 5th Baron FitzHugh of Ravensworth Castle.[1]

She is best known for being the great-grandmother of Queen consort Katherine Parr and her siblings, Anne and William, as well as one of the sisters of Sir Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, known as the ‘Kingmaker’. Her family was one of the oldest and most powerful families of the North. They had a long standing tradition of military service and a reputation for seeking power at the cost of the loyalty to the crown as was demonstrated by her brother, the Earl of Warwick.[2] Warwick was the wealthiest and most powerful English peer of his age, with political connections that went beyond the country’s borders. One of the main protagonists in the Wars of the Roses, he was instrumental in the deposition of two kings, a fact which later earned him his epithet of “Kingmaker”.

Lady Alice was born in her mother’s principal manor in Wessex.[3] Lady Alice is thought to be named after her mother, Lady Alice Montacute.[3] Lady Alice Neville was the third daughter of six, out of the ten children of Sir Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury jure uxoris and Lady Alice Montague, suo jure 5th Countess of Salisbury. Alice’s godmother was her paternal aunt, Lady Anne Neville, Duchess of Buckingham, wife of Sir Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham.[3]

By her paternal grandmother, Lady Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland, she was the great-great-granddaughter of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. Lady Joan Beaufort was the legitimized daughter of Prince John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and Aquitaine, and his mistress, later wife, Katherine Roët Swynford. As such, Lady Alice was a great-niece of King Henry IV of England. By her father, the Earl of Salisbury, she was niece to Cecily, Duchess of York, mother to Edward IV and Richard III. Alice’s mother was the only child and sole heiress of Sir Thomas Montacute, 4th Earl of Salisbury by his first wife Lady Eleanor Holland [both descendants of King Edward I]. Alice’s maternal grandmother, Lady Eleanor Holland, was the granddaughter of Princess Joan of Kent, Countess of Kent and Princess of Wales. Princess Joan was of course the mother of the ill-fated King Richard II making Eleanor Holland his grandniece. Princess Joan herself was the daughter of Prince Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent; son of Edward I by his second wife, Marguerite of France.

Lady Alice’s siblings included:

- Lady Joan Neville, Countess of Arundel (1423-9 September 1462), who married William FitzAlan, 16th Earl of Arundel. They had issue including the 17th Earl.

- Lady Cecily Neville, Duchess of Warwick (1424-28 July 1450), who first married Henry de Beauchamp, 1st Duke of Warwick and the only King of the Isle of Wight (as well as of Jersey and Guernsey). Their only daughter was Anne Beauchamp, 15th Countess of Warwick. Her title as Countess of Warwick was inherited by her paternal aunt, Lady Anne Beauchamp, who married her maternal uncle, Sir Richard Neville, who became the 16th Earl by right of his wife. Cecily’s second husband was John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester.

- The infamous, Sir Richard “the Kingmaker” Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (1428–1471), whose younger daughter, Lady Anne, would marry Edward, Prince of Wales, son of Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou who died in 1471, and secondly Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester who would become the last Plantagenet king as Richard III. By Richard, Queen Anne had one son; Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales. Queen Anne died in 1485 at the age of 28 perhaps of tuberculosis. Neville’s eldest daughter, Lady Isabel, became Duchess of Clarence as the wife of Prince George, Duke of Clarence, who was brother to Edward IV and Richard III. Their children would be the last line of the Plantagenets’, ending with Lady Margaret, suo jure 8th Countess of Salisbury who was executed under the orders of her cousin’s son, King Henry VIII.

- Sir John Neville, 1st and last Marquess of Montagu (c. 1431 – 14 April 1471), who’s son George, was intended to marry his cousin, Princess Elizabeth of York. Instead, Elizabeth became wife of the Tudor King Henry VII. In anticipation, George was made Duke of Bedford in 1470. John’s daughter, Margaret, married Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk, but had no issue; the marriage was annulled on the grounds of consanguinity. Coincidentally, Neville’s granddaughter and niece of Margaret, Anne Browne, would also marry Charles and have issue; Lady Anne Brandon, Baroness Grey of Powis and Lady Mary Brandon, Baroness Monteagle.[12][13]

- George Neville, Archbishop of York and Chancellor of England (1432–1476)

- Lady Eleanor Neville, Countess of Derby (1438–1504); her husband Sir Thomas Stanley, Earl of Derby crowned Henry Tudor as King Henry VII after the death of Richard III at Bosworth Field. He would go on to marry Henry’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond.

- Lady Katherine Neville, Baroness Hastings (1442- after 22 November 1503) who married firstly William Bonville, 6th Baron of Harington and secondly William Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings. By Bonville, she was the mother of Cecily Bonville who was great-grandmother to the nine day queen of England, Lady Jane Grey.

- Sir Thomas Neville (1443–1460), who was knighted in 1449 and died at the Battle of Wakefield.

- Lady Margaret Neville, Countess of Oxford (1444-20 November 1506), who married John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford. No issue.

Life

Ravensworth Castle, ancestral home to the Barons FitzHugh

Alice and her siblings would visit their grandmother, Lady Joan Beaufort, the Countess of Westmorland, often at her manors in Middleham and Sheriff Hutton. After Beaufort’s death in 1440, her father inherited the manors and Alice and her siblings began living in the manors on a more permanent basis. At the age of four, Alice started lessons in Latin and French with an introduction to law and mathematics. Alice began every day by attending mass with her family. As the tradition of most nobility of the times, the parents were absent attending to the King’s matters or personal business. They only saw each other on special occasions.

The uneasy years of the 1450s were used by Salisbury to conclude the marriages of the rest of his children. The rest of the daughters married members of solid, baronial families, but in some cases poorer and less influential than the other matches Salisbury made for his elder daughters. Salisbury obviously preferred to arrange great, rather than acceptable marriages, but as the War of the Roses continued his ability to secure them became more difficult.[3] With the death of Salisbury’s mother, Lady Joan Beaufort, his direct link to the royal family (Henry VI) was broken. That may have also stippled his matches for his daughters. Henry VI was a second cousin of the half blood. However, the children of Salisbury’s sister, the Duchess of York — were his nephews and nieces (the future King Edward IV and King Richard III, etc).

Lady Alice was either married in her late teens or early twenties to her father’s associate, Sir Henry, 5th Baron FitzHugh of Ravensworth. Lord FitzHugh had been a long-standing supporter of the Neville family; he supported Alice’s father, the Earl of Salisbury, in his dispute with the Percy family in the 1450s. Lord FitzHugh also served with the earl on the first protectorate council. Lord FitzHugh would go on to become a close ally of Alice’s brother, “Warwick, the Kingmaker”, during the War of the Roses. After her marriage to Lord FitzHugh, Alice immediately began to have children.

Lady Fitzhugh was very much the same temperament of her brother the Earl of Warwick. Although her husband, Henry, Lord FitzHugh is generally given credit for instigating the 1470 rebellion which drew King Edward IV into the north and allowed a safe landing of the Earl of Warwick in the West country, the boldness of the stroke is far more in keeping with Alice, Lady Fitzhugh’s temperament and abilities than with her husband’s.[8]

After the death of her husband on 3 June 1472, Lady Fitzhugh along with her children Richard, Roger, Edward, Thomas, and Elizabeth joined the Corpus Christi guild at York.[9] Lady FitzHugh never remarried. As Dowager Lady FitzHugh, Alice spent much of her widowhood at West Tanfield in Yorkshire as to not overshadow the new Lady FitzHugh, Elizabeth Borough (or Burgh), daughter of Sir Thomas Borough (or Burgh), 1st Baron of Gainsborough and his wife Margaret de Ros.[3] [see note 1]

Lady Alice, who was close to her niece Lady Anne [Neville], Duchess of Gloucester, was very supportive of Anne’s husband, Richard, Duke of Gloucester after he had become Lord Protector of the Realm. After watching the outcome of her brother, the Earl of Warwick’s, involvement with both the houses of York and Lancaster she influenced her family members to support the Duke of Gloucester as well.[2] Richard was also related to Alice who was his cousin through his mother Lady Cecily Neville, Duchess of York. Alice was most likely tired of the lost family members from the Wars between the Houses of York and Lancaster, and no doubt wanted to stay in favour with whomever came to the throne next, which would be the Duke as King Richard III of England and the Duchess, Anne Neville, who became Queen of England in June 1483.

The FitzHugh family was invited to the Coronation. The Dowager Lady Alice FitzHugh, her daughters Lady Elizabeth Parr and Lady Anne Lovell, and her daughter-in-law Lady Elizabeth FitzHugh were given presents from the King which included yards of the grandest cloth available to make dresses. Alice’s gifts are described as ‘long gownes made of vij yerdes of blue velvet and purfiled with v yerdes and a quarter of crymsyn satyn and vij yerdes of crymysy velvet and purfiled with v yerdes and a quarter of white damask’.[14]

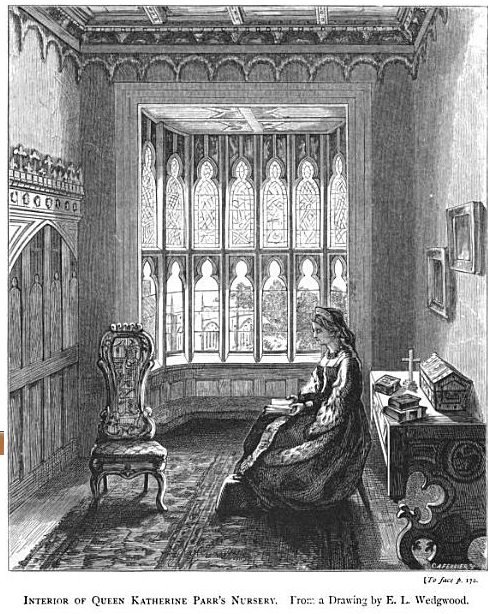

It has been said that at the coronation in 1483, it was Alice and Elizabeth who were two of the seven noble ladies given the honour to ride behind the queen in her coronation train.[2] Further research states it was the Dowager Lady Alice FitzHugh, the Lady Elizabeth FitzHugh, and Lady Anne, Viscountess Lovell who rode behind the Queen. But the Dowager Lady [Alice] FitzHugh’s daughter, Elizabeth FitzHugh is apparently listed under her marital name ‘Lady Elizabeth Parr’ in contemporary documents. So, it would seem that the “Lady Elizabeth FitzHugh” listed in documents was actually the current Lady FitzHugh who was Elizabeth Burgh (or Borough).[see note 1] The three women were all noblewoman (by right of their husband). Alice’s daughter, Elizabeth, had only married a knight. Lady Alice and her daughter, Elizabeth, were appointed by Queen Anne as her ladies-in-waiting. The position of lady-in-waiting to the Queens of England became a family tradition spanning down to Lady FitzHugh’s great-granddaughter, Lady Anne Herbert (Parr), Countess of Pembroke who apparently served all of King Henry VIII’s six wives.[7]

There isn’t much on her later life after her cousin, the King, was defeated at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. The new King, Henry VII, was a Lancastrian from the House of Tudor. He married her cousin, Elizabeth of York, who was the eldest of the children of King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. It was to be a union of the two houses of Lancaster and York. There is no evidence Alice stayed at court to attend the new Queen. She probably retired to West Tanfield.

Lady FitzHugh died on 22 November 1503 probably at West Tanfield, Yorkshire, where she spent her widowhood. There is no record as to where Alice chose to be buried. She may have chosen to be buried with her husband, Lord FitzHugh, and his ancestors at Jervaulx Abbey in Yorkshire or the church of St. Nicholas at West Tanfield (Yorkshire) near the Marmion Tower where she spent the last years of her life.[3]

Issue

Lady Alice and Lord Fitzhugh had 11 children; five sons and six daughters:

- Henry, 6th Baron FitzHugh who married Hon. Elizabeth Burgh, daughter of Thomas Burgh, 1st Baron Burgh; their son, George, inherited the barony of FitzHugh, but after his death in 1513 the barony fell into abeyance between his aunt Alice and her nephew Sir Thomas Parr, son of his other aunt Elizabeth. This abeyance continues to the present day.[10]

- George FitzHugh, Dean of Lincoln (1483-1505)[10]

- Alice FitzHugh, Lady Fiennes, married Sir John Fiennes, the son of Sir Richard Fiennes and Joan Dacre, suo jure 7th Baroness Dacre.[11][10] Their descendants became Barons/Baroness Dacre.

- Elizabeth FitzHugh, grandmother to Queen consort Katherine Parr, who married firstly Sir William Parr, 1st Baron Parr of Kendal [staunch supporter of King Edward IV], then Sir Nicholas Vaux, later 1st Baron Vaux of Harrowden [a Lancastrian protege of Lady Margaret Beaufort].[10] By both husbands she had issue.[10]

- Agnes FitzHugh, wife of Francis Lovell, 1st Viscount Lovell.[10]

- Margery FitzHugh, who married Sir Marmaduke Constable.[10]

- Joan FitzHugh, who became a nun.[10]

- Edward FitzHugh (dsp.)[10]

- Thomas FitzHugh (dsp.)[10]

- John FitzHugh (dsp.)[10]

- Eleanor FitzHugh[10]

Genealogy

By her mother, Alice Neville descended from Henry I of England, Henry II of England, John I of England, Henri I of France, William I “the Lion” of Scotland, David I of Scotland, and by two children of King Edward I of England: Princess Joan of Acre, daughter of Edward and his first wife, Eleanor of Castile by her marriage to Sir Ralph Monthermer, Earl of Gloucester and Hereford; Prince Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent, son of Edward and his second wife, Princess Marguerite of France. She also descended from Infanta Berenguela of León, Empress of Constantinople.

Lady Alice’s maternal grandmother was Lady Eleanor Holland. Eleanor’s sister, Lady Joan Holland married Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, the younger son of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. The marriage resulted in no children, but Edmund married again to Infanta Isabella of Castile, the younger sister of Infanta Constance of Castile, the second wife of John of Gaunt. If that doesn’t give you a headache — one of their sons was Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge who married Anne Mortimer, niece of Lady Eleanor Holland who descended from Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, another son of Edward III — their son (Richard and Anne Mortimer’s son), Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, already a cousin, became the husband of Lady Alice’s aunt, Cecily Neville, Duchess of York. Through the Duchess of York, Alice was first cousins of Edward IV of England; Edmund, Earl of Rutland; Margaret of York; George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, and Richard III of England.

Lady Fitzhugh’s niece, Anne of Warwick, daughter of Warwick, was the wife of Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who became King of England as Richard III. On April 1483, the Duke of Gloucester was appointed as Lord Protector to his nephew Edward V of England, who was only 12 at the time. After assembling a council which declared his brother, King Edward IV’s children by Elizabeth Woodville illegitimate, he threw Edward V and his brother into the Tower of London and the children were never seen again. Richard’s death in 1485 during the Battle of Bosworth Field, ended the House of York and the the Plantagenet dynasty.[4] Queen Anne’s elder sister, Lady Isabella Neville would marry King Richard III’s brother, the Duke of Clarence; this marriage would produce the last generation of Plantagenet’s — Lady Margaret Plantagenet, the 8th Countess of Salisbury, better known as Margaret Pole and her brother Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick.[5] Both would be executed by the new dynasty of the House of Tudor; Edward by King Henry VII and Margaret by Henry’s son, King Henry VIII.[6]

Notes

- Elizabeth Burgh was of the future family of Katherine Parr’s first husband, Sir Edward. Elizabeth was sister to the 2nd Baron Burgh who is sometimes mistaken as the first husband of Katherine Parr.

References

- ^ Charles Mosley, editor, Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage, 106th edition, 2 volumes (Crans, Switzerland: Burke’s Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 1999), volume 1, page 17.

- ^ ab Linda Porter. Katherine the Queen; The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII. Macmillan, 2010.

- David Baldwin. The Kingmaker’s Sisters: six powerful women in the War of the Roses. The History Press, 2009.

- ^ Kendall, Paul Murray (1955). Richard The Third. London: Allen & Unwin. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0049420488.

- ^ Charles Mosley, editor, Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage, 106th edition, 2 volumes (Crans, Switzerland: Burke’s Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 1999), volume 1, page 16.

- ^ DWYER, J. G. “Pole, Margaret Plantagenet, Bl.” New Catholic Encyclopedia. 2nd ed. Vol. 11. Detroit: Gale, 2003. 455-456.

- ^ Susan James. Catherine Parr: Henry VIII’s Last Love. The History Press; 1st Ed. edition (January 1, 2009).

- ^ Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society , Volume 94. Printed by T. Wilson and sons, 1994.

- ^ Jennifer C. Ward. Women in England in the Middle Ages. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006. pg. 186.

- ^ abcdefghijk Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry (Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A.: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2004), page 326, 566.

- ^ G.E. Cokayne; with Vicary Gibbs, H.A. Doubleday, Geoffrey H. White, Duncan Warrand and Lord Howard de Walden, editors, The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, new ed., 13 volumes in 14 (1910-1959; reprint in 6 volumes, Gloucester, U.K.: Alan Sutton Publishing, 2000), volume II, page 135.

- Maria Perry. ”The Sisters of Henry VIII: The Tumultuous Lives of Margaret of Scotland and Mary of France,” Da Capo Press, 2000. pg 84.

- Charles Mosley, editor, Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th edition, 3 volumes (Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.A.: Burke’s Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003), volume 1, page 1103

- The Coronation of Richard III, the Extant Documents pp.169.170. Edited by Anne F Sutton and P W Hammond. (Original Source: THE SIX SISTERS OF WARWICK THE KINGMAKER by Medieval Potpourri)

See also

Reading

- The Kingmaker’s Sisters: Six Powerful Women in the Wars of the Roses by David Baldwin

Written by Meg McGath

© 11 March 2011

Update: 13 May 2025

Would it surprise you to know that even Katherine of Aragon and Anne of Cleves had Edward I in their pedigree?

Would it surprise you to know that even Katherine of Aragon and Anne of Cleves had Edward I in their pedigree?

![The nursery and apartments of the dowager queen with Lady Anne Herbert standing by [the queen's sister] © Meg McGath, 2012.](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/sudeley1.png?w=584)

![The nursery as it is today; the woman portrayed here is Queen Katherine's sister, Lady Anne Herbert [later Countess of Pembroke] who was Katherine's groom.](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/sudeley175.png?w=584)