Sir John Neville, 3rd Baron Latimer of Snape Castle (17 November 1493–2 March 1543) was an English nobleman of the House of Neville. Latimer was Katherine Parr’s second husband and Latimer’s third and final wife. His family was one of the oldest and most powerful families of the North. They had a long standing tradition of military service and a reputation for seeking power at the cost of the loyalty to the crown as shown by Sir Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick [Warwick, the Kingmaker], John’s 1st cousin, twice removed.[2]

Latimer’s branch of the Neville family was in line for the Earldom of Warwick; his great-grandmother, Lady Elizabeth Beauchamp was a daughter of the 13th Earl of Warwick by his first wife. The 13th Earl’s heir was his only son, Henry, by his second marriage Lady Isabel le Despenser [granddaughter of Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York]; he was created Duke of Warwick. Warwick married to the future “Warwick, the Kingmaker’s” sister, Lady Cecily Neville. The Duke’s only child and heir by Cecily was a daughter, Lady Anne, who became Countess in her own right. After her early death the Earldom and inheritance became an issue.[see note 1] Due to the affiliation, Lord Latimer dealt with quite a bit of sibling rivalry. Legal actions were taken by his younger brothers and Latimer, at the time of his marriage to Katherine in 1534, was having financial difficulties. He lived chiefly at Snape Castle, Yorkshire, but sometimes at Wyke in Worcestershire.

Born about 17 November 1493,[1] he was eldest son of Sir Richard Neville, 2nd Baron Latimer by Anne, daughter of Sir Humphrey Stafford. His grandfather and heir to the Barony, Sir Henry, had been involved in the War of the Roses and in 1469 was killed at the battle of Edgecote fighting for Henry VI [the last Lancastrian king]. The fortunes of this branch of Nevilles were saved by Neville’s sympathetic granduncle, Cardinal Thomas Bourchier [uncle of Neville’s paternal grandmother Joan], who procured the wardship of the 2nd Baron and preserved his inheritance.

He came to court where he was one of the gentlemen-pensioners. Neville doesn’t really enter into history until 1513 when he accompanied Henry VIII to Northern France and was knighted after the taking of Tournai. He had taken part in about 1517 in the investigation of the case of the Holy Maid of Leominster. He was knight of the shire (MP) for Yorkshire in 1529 which was a step in progress even if he owed it to his father. The representation of the county was somewhat of a family affair as his fellow knight was Sir Marmaduke Constable, whom Neville took precedence over most likely due to his noble inheritance. He was not a member of the Commons for long as his father died before the end of 1530 and he had livery of his lands and succeeded to the House of Lords as the 3rd Baron on 17 March 1531.

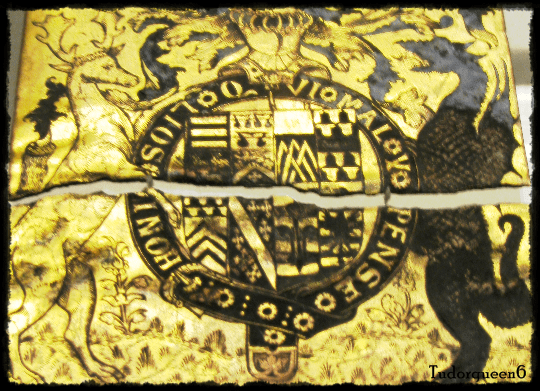

![Tomb of Queen Katherine at Sudeley features the her family arms impaled with that of her four husbands [Latimer & Parr]. Copyright Meg McGath](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/latimer-lady.png?w=584)

Tomb of Queen Katherine at Sudeley features the her family arms impaled with that of her four husbands [Latimer & Parr]. © Meg McGath [2012]

Latimer was a supporter of the old religion and bitterly opposed the king’s divorce and remarriage and it’s religious ramifications. In 1536, within two weeks of the riot in Louth, a mob appeared before the Latimer’s home threatening violence if Lord Latimer did not join their cause. Katherine watched as her husband was dragged away by the rebels. As prisoner of the rebels, conflicting stories of which side Latimer was truly on began to reach Cromwell and the King in London. The rebellion in Yorkshire put him in a terrible dilemma. If he was found guilty of any kind of treason his estates would be forfeited leaving Katherine and her step-children penniless. The King himself, wrote to the Duke of Norfolk pressing him to make sure Latimer would ‘condemn that villain Aske and submit [himself] to our clemency’.[11] Latimer was more than happy to comply. Both Katherine’s brother, William Parr and uncle, William Parr, 1st Baron Parr of Horton fought with the Duke of Norfolk and the Duke of Suffolk against the rebellion. Katherine’s brother, Sir William Parr, who had been in the service of the Duke of Richmond [natural son of King Henry VIII and Elizabeth Blount], blocked the Great North Road at Stamford, with a large force of armed men, they were in the way of anyone coming up from London. The only substantial Lincolnshire landowner that the King could depend on was his friend and brother-in-law, the Duke of Suffolk.It is to most likely to Katherine’s credit that Lord Latimer survived; both her brother and uncle probably intervened at one point and saved Lord Latimer’s life.[10] Never the less, Latimer represented the insurgents at the conferences with the royal leaders in November 1536, and helped to secure amnesty.[12]

In January 1537, Katherine and her step-children were held hostage at Snape Castle during the uprising of the North; the “Bigod Rebellion” which was lead by Sir Francis Bigod of Settrington. The rebels ransacked the house and sent word to Lord Latimer, who was returning from London, that if he did not return immediately they would kill his family. When Lord Latimer returned to the castle he somehow talked the rebels into releasing his family and leaving, but the aftermath to follow with Lord Latimer would prove to be taxing on the whole family.[10] It is probable that Katherine made sure that her husband did not join the uprising.[12]

The family would later move south after the executions of the rebels which pleased Cromwell and the King. Although now charges were found, Latimer’s reputation which reflected upon Katherine, was tarnished for the rest of his life. He spent the last seven years of his life blackmailed by Cromwell. Latimer was called away frequently to do the biding of Cromwell and the King and be present during Parliament from 1537-42. With Cromwell’s fall in 1540, the Latimer’s reclaimed some dignity and as Lord Latimer attended Parliament in 1542 he and Katherine spent time in London that winter. The atmosphere of the court was much different from the rural and parochial estates. It was at court that Katherine could find the latest trends, not only in religious matters, but in frivolous matters such as fashion and jewellery which she loved.[10]

By the winter of 1542, Lord Latimer’s health had broken down after a grueling life of what some would call ‘political madness’. Katherine spent the winter of 1542-1543 nursing her husband. John Neville, Lord Latimer, died in 1543. In Lord Latimer’s will, Katherine was named guardian of his daughter, Margaret, and was put in charge of Lord Latimer’s affairs which were to be given over to his daughter at the age of her majority. Latimer left Katherine Stowe Manor, Wyke [or Wike] Manor, and other properties. He also bequeathed money for supporting his daughter and in the case that his daughter did not marry within five years, Katherine, was to take £30 per annum out of the income to support her step-daughter. Katherine was left a rich widow faced with the possibility of having to return north after Lord Latimer’s death.[10]

![Wyke Manor in Wick, Worcestershire. [Wikipedia]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/wick_manor.jpg?w=584)

Wyke Manor in Wick, Worcestershire. [Wikipedia]

“Here in a monument broken all a pieces lieth entombed the body of John Nevill Lord Latimer whose widow Katherine Parr daughter of Sir Thomas Parre of Kendal and sister to William Lord Parre Marquesse of Northampton was the sixth and last wife to King Henry the Eight. He died in the year 1542 [incorrect date].”[9]

Family

Latimer married three times:

1. By 1520,[3] Dorothy de Vere (d. 7 February 1527), the daughter of Sir George de Vere and Margaret Stafford. Dorothy was the sister and co-heiress of John de Vere, 14th Earl of Oxford. She is buried in Wells, North Yorkshire in St. Michael’s; which is next to Snape Castle. The couple had two children:

- John Neville, 4th Baron Latimer (1520[4]-1577), married Lady Lucy, daughter of Henry Somerset, 2nd Earl of Worcester and Anne Browne [daughter of Sir Anthony Browne and Lady Lucy, herself a daughter of John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu] by whom he left four daughters and co-heiresses, of whom Dorothy married Thomas Cecil, 1st Earl of Exeter.[2] On his death, the Barony of Latimer fell into abeyance between his four daughters and co-heirs, and so remained until 1913, when Francis Burdett Thomas Coutts-Nevill was summoned to Parliament by writ, dated 11 February 1913.[5][6] Latimer was buried near Snape Castle in St. Michael’s Church, Wells, within Nevilles’ Chapel.[7]

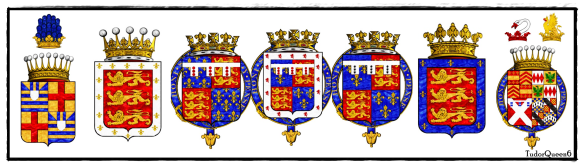

Effigy and tomb of the 4th Lord Latimer in Nevilles’ Chapel, Wells, North Yorkshire Well Village Website © Well Parish Council 2011

- Hon. Margaret Neville (1525[7]-1546), was betrothed to her cousin Ralph Bigod in 1534, before the Bigod Rebellion. Ralph was the son of the rebel Sir Francis Bigod. The betrothal was broken most likely to the Rebellion. She died at age twenty-one, unwed, and d.s.p. [no children].[2]

2. On 20 June 1528, he obtained a marriage license to Elizabeth Musgrave (d. 1530), daughter of Sir Edward Musgrave of Hartley and Joan Warde, by whom he had no issue.[1][2] Elizabeth was in fact a cousin to Katherine Parr sharing Sir Thomas Tunstall and Isabel Harrington [3rd cousins, twice removed]; the 3rd Lord FitzHugh and Elizabeth Grey [4th cousins]; and both Sir Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland and Lady Joan Beaufort — Elizabeth descended from Westmorland’s children, Sir Ralph [4th cousin, once removed] and Hon. Philippa [4th cousin], by his first wife, Lady Margaret Stafford, who married his stepmother’s (Lady Joan Beaufort) daughter, Hon. Mary Ferrers, the daughter from Lady Joan’s first marriage to of Robert, Lord Ferrers [4th cousin, once removed]. These last three connections to Westmorland, Lady Joan Beaufort, and Lady Margaret Stafford also made Elizabeth a cousin of her husband Lord Latimer.

3. In Summer 1534, Katherine, daughter of Sir Thomas Parr of Kendal and widow of Sir Edward Borough (d. circa April 1533), son of Thomas Burgh, 1st Baron Burgh.[2]

Ancestry

By his father, Latimer descended from King Edward III of England twice. Latimer’s grandparents were Sir Henry Neville, heir to the barony of Latimer and Earldom of Warwick, and the Hon. Joan Bourchier. Henry Neville was the heir and eldest son of Sir George, 1st Baron Latimer of Snape and Lady Elizabeth Beauchamp [through whom the Latimer’s claimed the Earldom of Warwick; Elizabeth was a daughter of the 13th Earl of Warwick by his first wife Hon. Elizabeth Berkeley, both descendants of Edward I]. George was a younger son of Sir Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland and his second wife, Lady Joan Beaufort. Lady Joan was the legitimized daughter of Prince John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster [son of Edward III and father of Henry IV of England] by his mistress, later wife, Katherine Roet.

Joan Bourchier was a granddaughter of Sir William, 1st Count of Eu and Lady Anne of Gloucester, daughter of Prince Thomas of Woodstock [youngest son of Edward III] and his wife, Lady Eleanor de Bohun [descendant of Edward I and Henry III]. This connection to the Bourchier family made Latimer a cousin of the Earls of Bath, Lords Dacre of the South, the Lady Margaret Bryan [governess of the King’s children], Lady Anne Bourchier [husband of Katherine Parr’s brother William Parr], and even the Duchess of Somerset Anne Stanhope. Perhaps the connection to the Bourchier’s, specifically Anne, wife of Sir William Parr, brought Katherine and Latimer together. Credit is usually given to Parr’s uncle also named Sir William and her cousin Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall.

Ancestry of John Neville, 3rd Lord Latimer; Queen Katherine and Latimer shared Lady Joan Beaufort and Sir Ralph, 1st Earl of Westmorland as common ancestors.

Notes

- The earldom passed to the 13th Earl’s male heir, Henry, from his second marriage to Lady Isabel le Despenser [a granddaughter of Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York]. Henry married Lady Cecily, a sister of the future Lord Warwick [Richard Neville] in 1436. At the same ceremony, Henry’s sister Lady Anne was married to Richard Neville, son of the 5th Earl of Salisbury. After the marriage, Henry was created Duke of Warwick in 1445. The couple had one child, a daughter Lady Anne, who inherited as suo jure 15th Countess of Warwick after the death of her father in 1446 [women could not inherit Dukedoms]. Lady Anne died young (d.1449). The title went to her her paternal aunt Lady Anne Beauchamp [whom she was most likely named after]. The title was passed to her husband, Richard Neville, who was also the maternal uncle of the last Countess. For the full story, see “Warwick Inheritance” on Lady Cecily’s page. The Warwick inheritance would be the subject of another feud after the death of Lord Warwick between his two daughters, Lady Isabel, Duchess of Clarence, and Lady Anne, Duchess of Gloucester and future queen of England. The title was bestowed upon Lady Isabel’s husband, George, Duke of Clarence (brother of King Edward IV and Richard III) and would go to his son, Edward, 17th Earl of Warwick, the last male Plantagenet.

References

- History of Parliament: a biographical dictionary of Members of the House of Commons, ed. Stephen Bindoff ‘Neville, Sir John I (1493-1543), of Snape, Yorks.,‘ 1982.

- Linda Porter. Katherine, the Queen. Macmillan, 2010.

- Cokayne, and others, The Complete Peerage, volume VII, page 483.

- Linda Porter. Katherine, the Queen, Macmillian, 2010. pg 65. *At the time of his father’s marriage to Katherine Parr in 1543, Neville was 14 yrs old.

- Charles Mosley, editor, Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th edition, 3 volumes (Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.A.: Burke’s Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003), volume 1, page 1363.

- G.E. Cokayne; with Vicary Gibbs, H.A. Doubleday, Geoffrey H. White, Duncan Warrand and Lord Howard de Walden, editors, The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, new ed., 13 volumes in 14 (1910-1959; reprint in 6 volumes, Gloucester, U.K.: Alan Sutton Publishing, 2000), volume VII, page 484.

- History of Village of Well, North Yorkshire, St. Michael’s

- Linda Porter. Katherine, the Queen, MacMillian, 2010. pg 66. *At the time of her father’s marriage to Catherine Parr in 1543, Margaret was aged 9.

- Richard Simpson. Some Accounts of the Monuments in Hackney Church, Billing and Sons, 1881; Chapter: Lady Latimer.

- Susan E. James. Catherine Parr: Henry VIII’s Last Love. The History Press, 2009 US Edition. pg 61-73.

- Letters and Papers, Foreign & Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII, II, no. 1174.

- Sir Sidney Lee. Dictionary of the National Biography, Vol XL, Smith, Elder and Co., 1894. pg 269.

Links

History of Parliament: Neville, Sir John I (1493-1543), of Snape, Yorks.