“Prayers or Meditations” by Queen Katherine Parr at Sudeley Castle. Photo by Meg Mcgath (2012).

First published in 1545, “Prayers or Meditations” by Queen Katherine Parr became so popular that 19 new editions were published by 1595 (reign of Elizabeth I). This edition was published in 1546 and bound by a cover made by the Nuns of Little Gedding. Located at Sudeley Castle, Winchcombe.

Queen Katherine Parr published two books in her lifetime. The first, ‘Prayers and Meditations’, was published while King Henry VIII was still alive [1545].

![Folger Shakespeare Library PDI Record: --- Call Number (PDI): STC 4824a Creator (PDI): Catharine Parr, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1512-1548. Title (PDI): [Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions] Created or Published (PDI): [1550] Physical Description (PDI): title page Image Root File (PDI): 17990 Image Type (PDI): FSL collection Image Record ID (PDI): 18050 MARC Bib 001 (PDI): 165567 Marc Holdings 001 (PDI): 159718 Hamnet Record: --- Creator (Hamnet): Catharine Parr, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1512-1548. Uniform Title (Hamnet): Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions Title (Hamnet): Praiers Title (Hamnet): Prayers or meditacions, wherein the minde is stirred, paciently to suffre all afflictions here, to set at nought the vayne prosperitee of this worlde, and alway to longe for the euerlastinge felicitee: collected out of holy workes by the most vertuous and gracious princesse Katherine Queene of England, Fraunce, and Ireland. Place of Creation or Publ. (Hamnet): [London : Creator or Publisher (Hamnet): W. Powell?, Date of Creation or Publ. (Hamnet): ca. 1550] Physical Description (Hamnet): [62] p. ; 8⁰. Folger Holdings Notes (Hamnet): HH48/23. Brown goatskin binding, signed by W. Pratt. Imperfect: leaves D2-3 and all after D5 lacking; D2-3 and D6-7 supplied in pen facsimile. Pencilled bibliographical note of Bernard Quaritch. Provenance: Stainforth bookplate; Francis J. Stainforth - Harmsworth copy Notes (Hamnet): An edition of: Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions. Notes (Hamnet): D2r has an initial 'O' with a bird. Notes (Hamnet): Formerly STC 4821. Notes (Hamnet): Identified as STC 4821 on UMI microfilm, reel 678. Notes (Hamnet): Printer's name and publication date conjectured by STC. Notes (Hamnet): Running title reads: Praiers. Notes (Hamnet): Signatures: A-D⁸ (-D8). Notes (Hamnet): This edition has a prayer for King Edward towards the end. Citations (Hamnet): ESTC (RLIN) S114675 Citations (Hamnet): STC (2nd ed.), 4824a Subject (Hamnet): Prayers -- Early works to 1800. Associated Name (Hamnet): Harmsworth, R. Leicester Sir, (Robert Leicester), 1870-1937, former owner. Call Number (Hamnet): STC 4824a STC 4824a, title page not for reproduction without written permission. Folger Shakespeare Library 201 East Capitol Street, SE Washington, DC 20003](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/prayers-and-meditations.jpg?w=584) Folger Shakespeare Library

Folger Shakespeare LibraryPDI Record:

—

Call Number (PDI):

STC 4824a

Creator (PDI):

Catharine Parr, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1512-1548.

Title (PDI):

[Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions]

Created or Published (PDI):

[1550]

Physical Description (PDI):

title page

Image Root File (PDI):

17990

Image Type (PDI):

FSL collection

Image Record ID (PDI):

18050

MARC Bib 001 (PDI):

165567

Marc Holdings 001 (PDI):

159718

Hamnet Record:

—

Creator (Hamnet):

Catharine Parr, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1512-1548.

Uniform Title (Hamnet):

Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions

Title (Hamnet):

Praiers

Title (Hamnet):

Prayers or meditacions, wherein the minde is stirred, paciently to suffre all afflictions here, to set at nought the vayne prosperitee of this worlde, and alway to longe for the euerlastinge felicitee: collected out of holy workes by the most vertuous and gracious princesse Katherine Queene of England, Fraunce, and Ireland.

Place of Creation or Publ. (Hamnet):

[London :

Creator or Publisher (Hamnet):

W. Powell?,

Date of Creation or Publ. (Hamnet):

ca. 1550]

Physical Description (Hamnet):

[62] p. ; 8⁰.

Folger Holdings Notes (Hamnet):

HH48/23. Brown goatskin binding, signed by W. Pratt. Imperfect: leaves D2-3 and all after D5 lacking; D2-3 and D6-7 supplied in pen facsimile. Pencilled bibliographical note of Bernard Quaritch. Provenance: Stainforth bookplate; Francis J. Stainforth – Harmsworth copy

Notes (Hamnet):

An edition of: Prayers stirryng the mind unto heavenlye medytacions.

Notes (Hamnet):

D2r has an initial ‘O’ with a bird.

Notes (Hamnet):

Formerly STC 4821.

Notes (Hamnet):

Identified as STC 4821 on UMI microfilm, reel 678.

Notes (Hamnet):

Printer’s name and publication date conjectured by STC.

Notes (Hamnet):

Running title reads: Praiers.

Notes (Hamnet):

Signatures: A-D⁸ (-D8).

Notes (Hamnet):

This edition has a prayer for King Edward towards the end.

Citations (Hamnet):

ESTC (RLIN) S114675

Citations (Hamnet):

STC (2nd ed.), 4824a

Subject (Hamnet):

Prayers — Early works to 1800.

Associated Name (Hamnet):

Harmsworth, R. Leicester Sir, (Robert Leicester), 1870-1937, former owner.

Call Number (Hamnet):

STC 4824a

STC 4824a, title page not for reproduction without written permission.

Folger Shakespeare Library

201 East Capitol Street, SE

Washington, DC 20003

Henry was said to be proud and at the same time jealous of his wife’s success. ‘Lamentations of a Sinner’ was not published until after Henry died [in 1547]. In ‘Lamentations‘, Catherine’s Protestant voice was a bit stronger. If she had published ‘Lamentations’ in Henry’s lifetime, she most likely would have been executed as a heretic despite her status as queen consort. Henry did not like his wives outshining him [i.e. Anne Boleyn]…hence her compliance and submission to the King when she found that she was to be arrested by the Catholic faction at court. Her voice may have been dialed down a notch, but once her step-son, the Protestant boy King Edward took the throne — she had nothing to hold her back. Her best friend, the Dowager Duchess of Suffolk, and brother Northampton encouraged Parr to publish.

A publication of the book The Lamentation of a Sinner c.1550 [after the death of Queen Katherine] from the book “Vivat Rex!: An Exhibition Commemorating the 500th Anniversary of the Accession of Henry VIII” by Arthur Schwarz

Published in 1547 [according to Sudeley Castle] after the death of King Henry VIII, “The Lamentation of a Sinner” was Katherine’s second book which was more extreme than her first publication. She was encouraged by her good friend the Duchess of Suffolk and her brother, the Marquess, to publish. The transcription of the title page here is… “The Lamentacion of a synner, made by the most vertuous Lady quene Caterine, bewailyng the ignoraunce of her blind life; let foorth & put in print at the inflance befire of the right gracious lady Caterine, Duchesse of Suffolke, and the ernest request of the right honourable Lord William Parre, Marquesse of Northampton.”

I was lucky enough to see a copy both a Sudeley Castle and at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. I am really interested in going to the Library and studying the actual book…one day!

Queen Katherine’s “Lamentations of a Sinner” on display at the Vivat Rex Exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Photo by Meg Mcgath (2009). See above for full description of the book the Folger has in their collection which can be seen in this photo.

Queen Katherine’s “Lamentations of a Sinner” on display at the Vivat Rex Exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Photo by Meg Mcgath (2009). See above for full description of the book the Folger has in their collection which can be seen in this photo.

![A publication of the book c.1550 [after the death of Queen Katherine]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/img_4646.png?w=584&h=886)

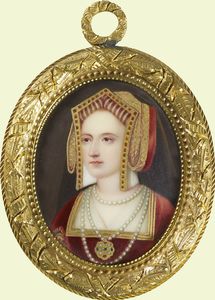

Queen Katharine of Aragon

Queen Katharine of Aragon

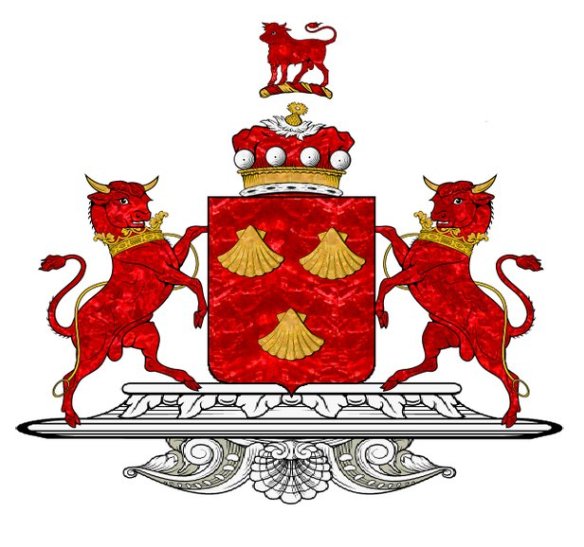

Queen Anne Bullen

Queen Anne Bullen

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Jane Seymour

Queen Anne of Cleve

Queen Anne of Cleve

Queen Katharine Howard

Queen Katharine Howard

Queen Katherine Parr

Queen Katherine Parr