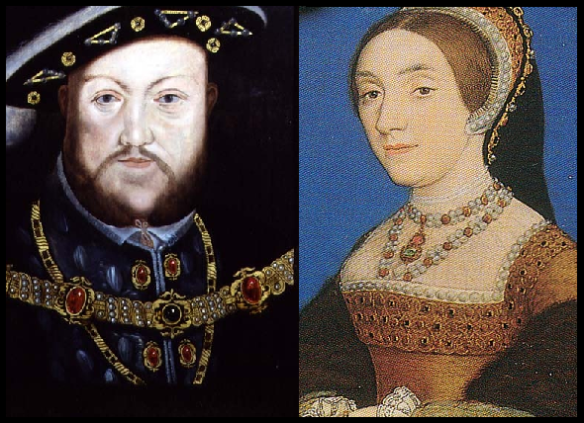

2nd Baron Vaux, sketch by Holbein.

Sir Thomas Vaux, 2nd Baron Vaux of Harrowden K.B. (25 April 1509[1] – October 1556), an English poet, was the eldest son of Sir Nicholas Vaux, 1st Baron Vaux and his second wife, Lady Anne [Green] (born circa 1489), daughter of Sir Thomas Green, Lord of Greens Norton, and Joan Fogge [cousin to Edward IV’s consort Elizabeth], daughter of Sir John of Ashford.[2][3] Vaux was educated at Cambridge University.[4] Vaux’s mother was the maternal aunt of queen consort Katherine Parr, while his wife, Elizabeth Cheney, was a paternal first cousin through her mother, Anne Parr.

Life

Lord Vaux by Holbein

In 1527, Vaux accompanied Cardinal Wolsey on his embassy to France.

Vaux privately disapproved of Henry VIII’s divorce from his first queen consort, Katherine of Aragon.[5]

It is interesting to note the family circle that he was in. The Parrs and their extended family stuck by the queen and all had an opinion of Henry’s “Great Matter.” Vaux’s aunt, Lady Maud Parr, was a lady-in-waiting and good friend to Queen Katherine of Aragon. Lady Parr was given her own quarters at court to attend the queen and when she gave birth to a baby girl in 1512, it is thought that she named her after the queen who may have been her godmother. Lady Parr stayed with the queen until her household was divided; Parr died in 1531. Lord Vaux’s sister, Katherine, would marry the staunch Catholic Sir George Throckmorton; the outspoken courtier who dared to speak out against the king.

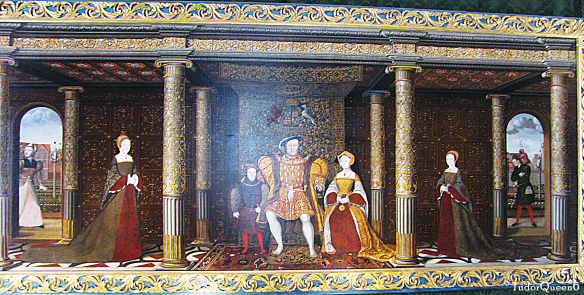

In 1531, Lord Vaux took his seat in the House of Lords. In 1532, he attended Henry VIII to Calais and Boulogne and was made Knight of the Bath at the coronation of Anne Boleyn on 1 June 1533. He was Lieutenant Governor of Jersey in 1536. Schism from Rome caused him to sell his offices; his position as Governor was sold to Sir Edward Seymour [later Lord Protector and Duke of Somerset]. He did not attend Parliament between 1534 and 1554.[5] Instead, Vaux retired to his country seat until the accession of Mary I, when he returned to London for her coronation.[5] Vaux was a friend of other court poets such as Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey.[5]

Family and issue

Lady Elizabeth Vaux [born Cheney] was cousin to Queen Katherine by her mother, Lady Anne [Parr].

Vaux’s father, Nicholas, had been previously married to

Hon. Elizabeth FitzHugh, daughter of Henry FitzHugh, 5th Lord FitzHugh of Ravensworth Castle and

Lady Alice Neville, as her second husband.

[3] By Elizabeth’s first marriage to Lord William Parr, she was the mother of Anne Parr, the mother of Thomas’ wife, Elizabeth Cheney, as well as Sir Thomas Parr, father to Queen Katherine.

[3]

From the marriage of Nicholas Vaux and the dowager Lady Parr, the 2nd Lord Vaux had three older paternal half-sisters; Katherine, Lady Throckmorton; Alice, Lady Sapcote; and Anne, Lady Strange.[3] After the death of Elizabeth in about 1507, the 1st Lord Vaux married secondly, in about 1508, to Anne Green, the older sister of Maud Green, Lady Parr who had married Sir Thomas Parr; thus making the 2nd Lord Vaux a first cousin to queen Katherine. At the time of the marriage, Lord Vaux was aged c.47, she was aged c.18.

Sir Thomas had been contracted to marry Elizabeth Cheney, daughter and heir of Sir Thomas Cheney of Irtlingburgh and Anne Parr (aunt to Queen Katherine), since 6 May 1511 [he was aged 2].[3] Thomas married Elizabeth between 25 April 1523 and 10 November 1523.[3] They had three children.

- Hon. William Vaux, 3rd Baron Vaux of Harrowden (born 1535), married firstly before 1557 to Elizabeth Beaumont, a distant cousin, by whom he had issue. In 1563, Vaux married to his second cousin, once removed, Mary Tresham, great-granddaughter of Sir William Parr, Baron Parr of Horton (uncle to Queen Katherine Parr) and had issue.

William, Lord Vaux of Harrowden (1535-1595), oil on panel 31 x 24½in. (78.8 x 62.2cm.). Inscribed “Willm. Lo. Vaux AE. ?de 40. ?ans 1575” 1575; Circle of Cornelius Ketel

- Hon. Nicholas Vaux

- Hon. Anne Vaux, married Reginald Bray of Stene, nephew of Edmund Braye, 1st Baron Braye; had issue.

Thomas Vaux died in October 1556.

Descendants

Among the many descendants of Thomas, Lord Vaux and his wife Elizabeth, Lady Vaux are:

- Lady Diana Spencer, Princess of Wales and thus HRH Prince William, Duke of Cambridge and HRH Prince Henry of Wales.

- Sarah, Duchess of York [by both parents], who was married to Prince Andrew, Duke of York and is mother to TRH Princess Beatrice and Princess Eugenie.

- HRH Princess Alice [Montagu-Douglas-Scott], Duchess of Gloucester, who married HRH Prince Henry, 1st Duke of Gloucester [son of King George V and Queen Mary]. They were parents to HRH Prince Richard, 2nd Duke of Gloucester (b.1944).

- Henry George Lascelles, 6th Earl of Harewood, husband to HRH Princess Mary, Princess Royal [only daughter of King George V and Queen Mary]. They had two sons including the 7th Earl of Harewood.

Art

Sketches of Vaux and his wife by Holbein are at Windsor, and a finished portrait of Lady Vaux is at Hampton Court. Another hangs in Prague. More info: The OTHER Elizabeth Cheney

Elizabeth, Lady Vaux of Harrowden, wife to the 2nd Baron Vaux.

Works

Two of his poems were included in the Songes and Sonettes of Surrey (Tottel’s Miscellany, published in 1557 (see 1557 in poetry). They are “The assault of Cupid upon the fort where the lover’s hart lay wounded, and how he was taken,” and the “Dittye … representinge the Image of Deathe,” which the grave-digger in Shakespeare’s Hamlet misquotes.[4]

Thirteen pieces in the Paradise of Dainty Devices, published in 1576 (see 1576 in poetry), are signed by him.[4] These are reprinted in Alexander Grosart’s Miscellanies of the Fuller Worthies Library (vol. iv, 1872).

Lord Vaux wrote during Queen Mary’s reign. The following lines by Vaux were first printed in The Paradise of Devices (1576).

OF A CONTENTED MIND

When all is done and said, in the end thus shall you find,

He most of all doth bathe in bliss that hath a quiet mind:

And, clear from worldly cares, to deem can be content

The sweetest time in all his life in thinking to be spent.

The body subject is to fickle Fortune’s power,

And to a million of mishaps is casual every hour:

And Death in time doth change it to a clod of clay:

Whenas the mind, which is divine, runs never to decay.

Companion none is like unto the mind alone; [or none]

For many have been harmed by speech, through thinking, few,

Fear oftentimes restraincth words, but makes not thought cease; [peace]

And he speaks best, that hath the skill when for to hold his

Our wealth leaves us at death; our kinsmen at the grave;

But virtues of the mind unto the heavens with us we have.

Wherefore, for virtue’s sake, I can bo well content,

The sweetest time of all my life to deem in thinking spent.

The introduction of a rhyme at the cesura or pause of the longer line in this measure breaks of its couplets into a four lined stanza. We have example of this by the same poet in what a MS copy describes as, “a dytte or sonet made by Lord Vaux in the time of the noble quene Marye representing the image of Death.” The first, third, and eighth stanzas of this poem, with a line from the last but one transferred to the third, were chosen by Shakespeare for the grave-digger’s song in fifth act of Hamlet; the clown giving, of course, his rudely remembered version of them [see Hamlet, act five].

So Shakespeare’s clown quoted it. This is the poem itself as written in Queen Mary’s reign by Lord Vaux:

THE IMAGE OF DEATH

I loathe that I did love,

In youth that I thought sweet,

As time requires for my behove

Methinks they are not meet.

My lusts they do me leave,

My fancies all arc fled,

And tract of time begins to weave

Grey hairs upon my head.

For Age with stealing steps

Hath clawed me with his crutch,

And lusty Life away she leaps

As there had been none such.

My Muse doth not delight

Me as she did before;

My hand and pen arc not in plight,

As they have been of yore.

For Reason me denies

This youthly idle rhyme;

And day by day to me she cries,

“Leave off these toys in time.”

The wrinkles in my brow,

The furrows in my face,

Say, limping Age will lodge him now.

Where Youth must give him place.

The harbinger of Death,

To mo I see him ride :

The cough, the cold, the gasping breath

Doth bid mo to provide.

A pickaxe and a spade,

And eke a shrouding sheet,

A house of clay for to be made

For such a guest most meet.

Methinks I hear the clerk,

That knolls the careful knell,

And bids mo leave my woeful work,

Ero Nature me compel.

My keepers knit the knot

That Youth did laugh to scorn,

Of me that clean shall be forgot,

As I had not been born.

Thus must I Youth give up,

Whose badge I long did wear;

To them I yield the wanton cup

That better may it bear.

Lo, here the bared skull,

By whose bald sign I know,

That stooping Age away shall pull

Which youthful years did sow.

For Beauty with her band

These crooked cares hath wrought,

And shipped me into the land

From whence I first was brought.

And ye that bide behind,

Have ye none other trust :

As ye of clay were cast by kind,

So shall ye waste to dust.

From: Cassell’s library of English Literature, selected, ed. and arranged by H. Morley

By Cassell, ltd.

References

- George Edward Cokayne. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom, Vol. XII/2, p. 219-221.

- Unknown author, David Faris. Plantagenet Ancestry of 17th Century Colonists, p. 39.

- Douglas Richardson, Plantagenet Ancestry, pg 326, 561-562, 566.

- Dominic Head. The Cambridge Guide To Literature In English, Cambridge University Press, Jan 26, 2006. pg 1151.

- John Saward, John Morrill, Michael Tomko. Firmly I Believe and Truly: The Spiritual Tradition of Catholic England, Oxford University Press, Nov 15, 2011. pg 92.

Researched and written by Meg McGath

© 26 March 2012