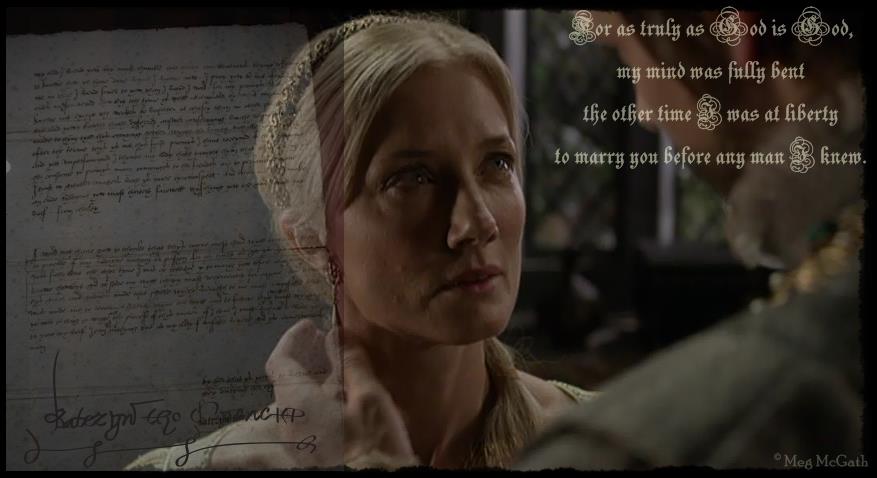

Portrait of Lady Elizabeth FitzGerald, Countess of Lincoln, known as “The Fair Geraldine” (1527-1589), second daughter by his second wife of the 9th Earl of Kildare. After Master of Countess of Warwick.

Lady Elizabeth FitzGerald, Countess of Lincoln (1527 – March 1590) was the daughter of Gerald “Gearóid Óg” FitzGerald, 9th Earl of Kildare, Lord Deputy of Ireland, and his second wife, Lady Elizabeth Grey. By her mother, she was a great-granddaughter of Queen consort Elizabeth Woodville and Lady Katherine Neville; sister of “Warwick, the Kingmaker”.

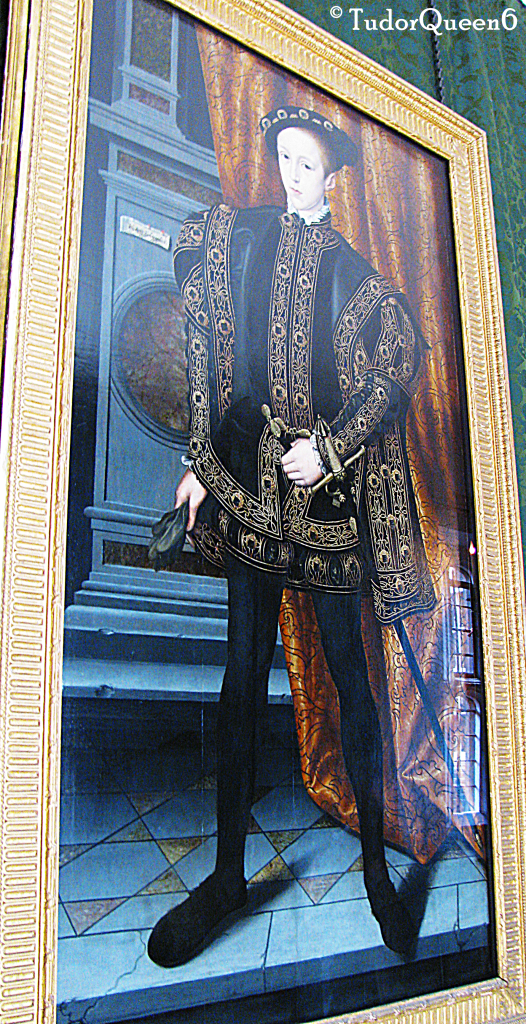

Her father was a prisoner in The Tower of London. In 1533, as a young girl, she came to England with her mother. In 1537, her half-brother and five uncles were executed at Tyburn for their part in the uprising and rebellion against King Henry VIII. At the time, Elizabeth was sent to the household of Lady Mary Tudor, eldest daughter of Henry VIII, at Hunsdon. Her younger brothers were sent to be raised alongside Prince Edward; heir to the throne.

When Elizabeth was eleven or twelve, the Earl of Surrey (Henry Howard) decided to write a poem about her–probably to improve her chances at marrying. Truth being that Elizabeth was an impoverished, Irish born gentlewoman who depended upon the welfare of The Tudors to improve her lot in life. The poem that is believed to be written about “Fair Geraldine” reads:

“From Tuscane came my lady’s worthy race ;

Fair Florence was sometime her ancient seat.

The western isle whose pleasant shore doth face

Wild Camber’s cliffs, did give her lively heat.

Foster’d she was with milk of Irish breast :

Her sire an Earl, her dame of Prince’s blood.

From tender years, in Britain doth she rest,

With Kinges child ; where she tasteth costly food.

Hunsdon did first present her to mine eyen :

Bright is her hue, and Geraldine she hight.

Hampton me taught to wish her first for mine ;

And Windsor, alas ! doth chase me from her sight.

Her beauty of kind ; her virtues from above ;

Happy is he that may obtain her love!.“

In 1543, Elizabeth married Sir Anthony Browne of Cowdray Park, son of Sir Anthony and Lady Lucy Neville, daughter of Sir John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu; brother to “Warwick, the Kingmaker”. As such, the two were cousins. This marriage also made Elizabeth aunt to another lady-in-waiting of Queen Katherine Parr, Lucy, Lady Latimer. Elizabeth was Browne’s second wife. With this marriage, Elizabeth took on the raising of stepchildren. Her stepdaughter, Mabel Browne, would marry Elizabeth’s brother, Gerald, 11th Earl of Kildare and become Countess of Kildare. His other daughter, Lucy, would marry a grandson of Sir Thomas More, Thomas Roper.

Anthony Browne’s mother had been previously married to Sir Thomas FitzWilliam and was thus a half brother to Sir William FitzWilliam, later Earl of Southampton. FitzWilliam had been an executor of Lady Maud Parr’s will. The FitzWilliam family was kin to the Parr family.

Browne’s career at court started around 1518. His career somewhat resembled that of his half-brother, William FitzWilliam. However, since the age of ten, William had been brought up in the household of Henry VIII. Browne probably owed his career at court to his mother who had been a niece of “Warwick, the Kingmaker”. Browne became friends with people such as Sir Thomas Boleyn. He had probably been previously acquainted with Sir Thomas Parr, who’s mother was also a niece of Warwick. Sadly, Parr died in 1517 cancelling any chances of becoming a greater Tudor statesman. Browne went to France where he spent time with Boleyn. By 1519, he was recalled to England. In his youth he took to jousting and was at the Field of the Cloth of Gold where he distinguished himself as a fine jouster. He became Ambassador to France in 1527 and as he spent more time at the court, his antipathy grew towards the French. He took part in the suppression of the Northern Rebellion. In 1538, Lady Margaret of Clarence, Countess of Salisbury was imprisoned at Cowdray until September 1539. Margaret was the last Plantagenet from the House of York. She had been the niece of Edward IV and Richard III, and cousin to Browne, by his mother, as Margaret descended from Warwick. Browne was then part of the commission that questioned Queen Catherine Howard after her supposed infidelities had been made known to the King. Browne even had hand written evidence given to him by one of the Queen’s ladies. He examined the Duchess of Norfolk on Catherine’s previous relations and was part of the commission that tried Dereham and Culpepper at Guildhall. By 1542, he had been appointed Captain of the gentlemen pensioners. In 1543, Browne was an attendant at the wedding of Henry VIII to his sixth and final wife, the Dowager Lady Latimer (Katherine Parr). In 1544, he served under Norfolk in the French War. In the defensive wars of 1545 and 1546, he was securing coastal defenses and advising the Earl of Hertford’s on troops and other such things. In 1547, Browne took part in the trial of the Earl of Surrey and questioned the Duke of Norfolk; of which he had been well acquainted.

Upon the death of Sir Anthony on 28 April 1548, Elizabeth joined the household of the Dowager Queen Katherine (Parr) at Chelsea. At this point, Katherine had married Lord Seymour and the two were living together. It is said, at this point, that Elizabeth renewed her friendship with Lady Elizabeth Tudor, who was also living with the Queen. However, Elizabeth Tudor would later be sent away from the household after the Queen would discover what her husband’s real intentions for Elizabeth were. So it’s not known how much time the two actually spent together.

In 1552, Elizabeth married to Edward Clinton, 9th Baron Clinton who was later created Earl of Lincoln. Elizabeth was the third wife of Lord Clinton. By his previous wives he had, had children and once again, Elizabeth would take on the role of stepmother. One stepdaughter was Katherine Clinton, who married William Burgh, who became the 2nd Baron Burgh. William was the younger brother to Queen Katherine Parr’s first husband, Sir Edward Burgh. Another stepdaughter, Frances, would marry to Giles Brydges, 3rd Baron Chandos of Sudeley Castle; where Queen Katherine Parr is buried.

Edward Clinton was the son of Thomas, 8th Baron Clinton and Jane Poynings. His stepfather was Sir Robert Wingfield, who was a nephew of Elizabeth Wingfield, grandmother of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. He married firstly to Elizabeth Blount, the mistress of King Henry VIII and mother to Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond in 1534. As such, there was a connection to the Parr family as Elizabeth Blount had been a lady to Queen Katherine of Aragon with Lady Maud Parr and Parr’s son, William, grew up in the household of Fitzroy. The two families were no doubt close to each other. After the death of Elizabeth, Clinton married secondly to Ursula Stourton, a niece of John Dudley, later Duke of Northumberland. By Ursula, Clinton had further issue, including his male heir.

Clinton became the 9th Lord Clinton upon his father’s death. He appears in history when King Henry VIII took on Boulogne, France in 1532. Lord Clinton took part in the suppression of the Northern Rebellion in 1536. Certain land holdings of the Abbeys were leased to Clinton, but later give to the King’s brother-in-law, the Duke of Suffolk. When the Duke of Richmond died in 1536, Clinton took on the role of Admiral of England. At that time, his wife, Elizabeth Blount, returned to court as a lady to Anne of Cleves. She would die shortly after. His next wife, Ursula, would take Elizabeth’s place at court as the new Lady Clinton. Clinton would serve in the Royal Navy from 1544-1547. He was knighted in 1544 by Edward, Earl of Hertford. Like Elizabeth FitzGerald’s former husband, Clinton also served Henry VIII in the siege of Boulougne in 1544 while Queen Katherine Parr was Regent of England. Clinton was appointed Governor of Bolougne in 1547 and defended the city against French attacks from 1549-50.

Later on in life, Elizabeth and her husband were involved in the plot to raise Lady Jane Grey to Queen, but like other nobility–they distanced themselves enough to prove to be loyal to Queen Mary. The pardon probably came from Clinton’s willingness to suppress the Wyatt Rebellion. Elizabeth may have also been remembered from her days in Mary’s household and was thus excused from her part in the charade. Others were not so fortunate. For example — Sir William Parr, Marquess of Northampton (brother to the late Queen) was not excused and was sent to The Tower. Anne Parr’s husband, however, who had married his daughter to Lady Jane’s sister, immediately annulled the union and they gained favor with Queen Mary again.

When Queen Mary died, her half sister, Elizabeth, became Queen. Elizabeth took on Elizabeth, Lady Clinton, as a lady-in-waiting and the two became good friends. However, Elizabeth got into some sort of trouble with the Queen and was accused of “frailty” and “forgetfulness of her duty”. The charges against Elizabeth were made by Archbishop Parker who also declared that she should be “chastised in Bridewell”. Historian, David Starkey, concludes that Parker thought Elizabeth was a strumpet.

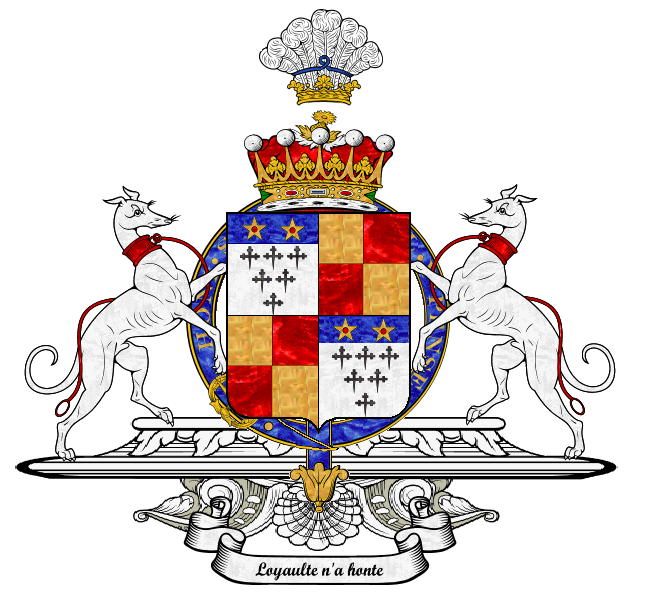

Under the rule of Elizabeth, Lord Clinton continued his role as Lord High Admiral from 1559-1585. In 1569, Elizabeth used her husband’s position as Lord Admiral to seize a ship that had been stolen. The man involved was arrested and Elizabeth kept the ship and cargo. In 1572, Lord Clinton stifled the Rising of the North brought about by the Earls of Northumberland and Westmorland. For his service, Lord Clinton was created Earl of Lincoln.

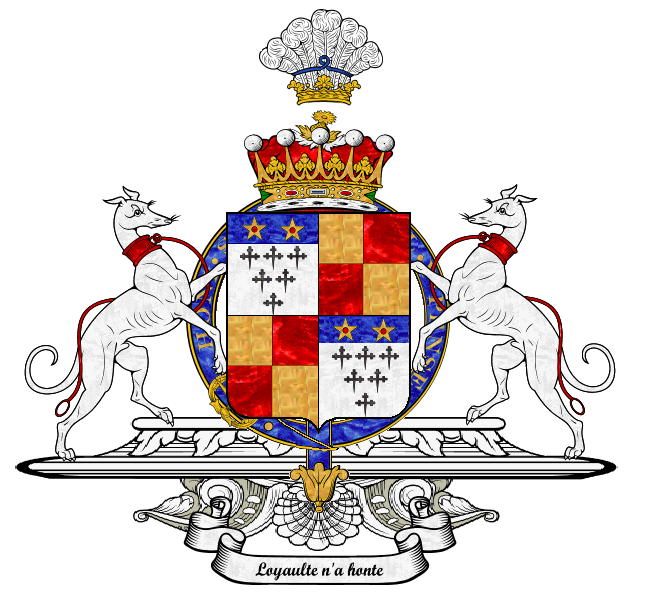

Edward Clinton, (1512–1585) 1st Earl of Lincoln, 9th Baron Clinton KG. Source: European Heraldry

Clinton died in 1585. In his will, he left the bulk of his estates to his wife for life.

Elizabeth, Countess of Lincoln died in 1590. She was buried in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, Windsor, UK, with her second husband, the Earl of Lincoln.

Links

Sources