A modern interpretation of Lady Mary’s stepmother’s was shown in the historical fiction series “The Tudors.”

Throughout the reign of Henry VIII, as many know, he had six different wives. The first of these wives was the daughter of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, Infanta Catalina; or as most have come to know her in England – Katherine of Aragon. Katherine came to England to marry the older brother of Henry who was then heir to the throne of England; Arthur, Prince of Wales. Shortly after their marriage Arthur died and Katherine was left a widow at an early age. To avoid returning her large dowry to her father Katherine was married to Arthur’s younger brother, then Henry, Duke of York. The marriage between Katherine and Henry produced only one child who would live to adulthood, a girl, the future Queen Mary I of England. In Tudor times, not having a male heir was particularly troublesome as the country had just been through a civil war in which Henry’s father seized the crown. Henry VIII was only the second Tudor monarch, a son of both the houses of Lancaster and York. Henry felt that a male heir was essential; after all, the last woman to reign as queen regent was the tumultuous reign of Empress Matilda, daughter of Henry I.

Born Princess Mary of England, Mary was the daughter of King Henry VIII and his first wife Katherine of Aragon. Her mother, after two decades of marriage to the King, had given birth to six children. Out of the six, only one would survive infancy, their daughter Mary. Katherine had produced no surviving sons, leaving their daughter, the future Mary I of England, as heiress presumptive at a time when there was no established precedent for a woman on the throne. At this time is when Henry began to take interest in one of Katherine’s ladies, Anne Boleyn. In Anne, Henry saw the possibility of having a male heir; to continue his father’s legacy. After going through a great bit of trouble – which included a break from Rome – Henry “divorced” Katherine and “married” Anne under his Church of England. This break and marriage would come to change England and inevitably changed Henry for the rest of his life. Henry would go on to have again, one daughter, with Anne. During this marriage, Princess Mary, now within her teens, went from being a legitimate Princess and daughter of Henry VIII to an illegitimate “bastard” under Henry’s new succession act. Mary was forced to live below the standards of what she had become accustomed to and was forced to accept that her mother was no longer queen of England. After only a few years of marriage to Anne, Henry became convinced that his second wife could not produce a male heir and literally disposed her for yet another lady-in-waiting, Jane Seymour. During her short reign, Jane tried to reconcile Henry with his daughter Mary. It was through this “precious” lady that Henry finally got what he wanted; a male heir, named Edward. To Henry’s misfortune, only twelve days after giving birth to Edward, Jane died. Henry would go on to marry three more times after Jane. Anne of Cleves, Katherine Howard, and a woman named Katherine Parr. It was the last of Henry’s wives who would come to reconcile Mary, along with her half-siblings, with Henry.

Katherine Parr was born in 1512. By both parents, Princess Mary was related to Katherine Parr. By her paternal grandparents, Mary was related by Katherine’s descent from the Beaufort’s, children of John of Gaunt, a son of Edward III making Mary by her paternal grandmother, Elizabeth of York, a 4th cousin. By the Woodville connection, they were 4th cousins. By her paternal grandfather, Henry VII (by Beaufort and Holland), Mary was a double 5th cousin, once removed. By her maternal grandmother, Isabel of Castile (by John of Gaunt), she was a fifth cousin and a fifth cousin, once removed. Jane Seymour is the next closest after Parr sharing Edward III (6th cousins, once removed).

Katherine was a few years older than Mary who was born in 1516. Katherine’s mother, Maud, had become a lady-in-waiting to Princess Mary’s mother shortly after her marriage to Sir Thomas Parr. Katherine was named after the queen and it is thought that the queen was her godmother.

Maud’s relationship with the Queen was unlike that of most queens and their ladies. It was a relationship that went much deeper than “giddy pleasure”. Both knew what it was like to lose a child in stillbirths and in infancy. It was Katherine Parr’s mother, Maud, who shared in the horrible miscarriages and deaths in which Queen Katherine would endure from 1511 to 1518. The two bonded over the issue, as Maud had experienced the death of her eldest, an infant boy, and later a miscarriage or early infant mortality after the birth of three healthy children. Because of these shared experiences, the queen and Maud became close.

After her husband died in 1517, Maud continued her position at court as one of Katherine of Aragon’s household and stayed close to the Queen even when her relationship with Henry started to decline in the 1520s. In 1525, when Henry’s infatuation with one of Katherine’s ladies, Anne Boleyn, became apparent, inevitably the ladies began to take sides. In these times, Queen Katherine never lost the loyalty and affection of women like Maud Parr, Gertrude Courtenay, and Elizabeth Howard, who had been with the Queen since the first years of her reign. Maud stayed with Queen Katherine until the end of her own life in 1531.

It has been said that Katherine Parr and Princess Mary were educated together. While Katherine’s mother attended on the queen, Katherine was at Parr house in Blackfriars, London. Katherine was not brought to court with her mother and probably the only time, if any, that she was in contact with the royal family was at her christening. Katherine and other daughters of the court were taught separately while Princess Mary, who had her own household, was taught by private tutors.

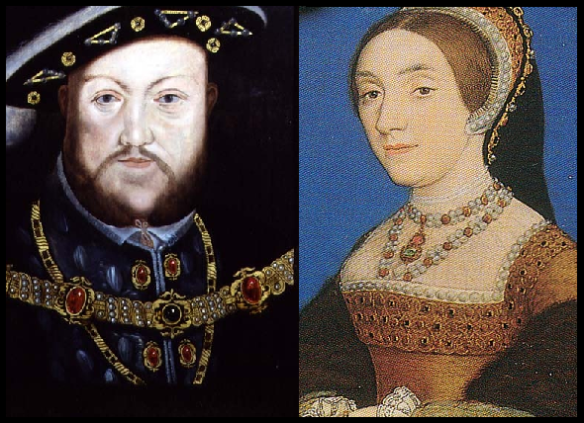

King Henry and his fifth consort Katherine Howard

After the disastrous marriage of the King and Katherine Howard, the King was no longer looking for flighty relationships that stirred his passions. Henry had learned a tough lesson with Katherine Howard and was determined more than ever to find an intelligent, honest, loving, and devoted wife. He wanted someone he could hold an actual conversation with; a companion. Another quality Henry looked for in a wife was someone who could be a perfect companion to his eldest daughter, now styled The Lady Mary Tudor. After years of tension and multiple step-mothers whom Mary had mixed relations with, Henry must have felt he owed her that much.

After the death of Katherine Howard, Mary enjoyed far greater favor from her father and presided over court feasts as if she was queen herself. For New Year’s, Mary was showered with lavish gifts from her father. Within the presents were ‘two rubies of inestimable value.’ However, it was during this time that Mary suffered from chronic ill-health linked to anxiety, depression, and irregular menstruation. These health issues along with others would continue until Mary’s death. Thankfully by Christmas 1542, Mary had recovered and was summoned to court for the great Christmas festivities. Her quarters at Hampton court were worked on day and night to prepare for her arrival. The Imperial Ambassador, Chapuys, reported that the King ‘spoke to her in the most gracious and amiable words that a father could address to his daughter.’

Katherine Parr would marry twice before her marriage to King Henry in 1543. Her first marriage would be to her distant relative, Sir Edward Borough in 1529; which ended in about 1533 with his death. Her next marriage was to her father’s second cousin, Sir John Neville, 3rd Baron Latimer of Snape in 1534. With this marriage, Katherine became Lady Latimer. She was the first of her family to marry into peerage since her great-aunt, Maud Parr, Lady Dacre. With this marriage also came two step-children from Latimer’s first marriage to Dorothy De Vere. For about a decade, Katherine would experience the joy of being a step-mother. It was during this time that she became extremely close to her step-daughter, Margaret, which was somewhat of a pre-cursor to Katherine’s future relationship with the Lady Elizabeth, Henry’s youngest daughter. By the time Lord Latimer had died, Katherine was left a rich widow and was asked by Latimer to look after his daughter until the age of her maturity. It has been said that Katherine became a lady in the household of Lady Mary during this time, but biographers Susan James and Linda Porter have different opinions. It was thought by James that because Mary remembered the kindness Katherine’s mother had shown her mother that she gladly took Katherine as one of her ladies. Porter disputes this saying it would have been below Katherine’s standing as the widow of a peer who had her own establishments and a large settlement from her husband’s death. Truth be told, many courtiers and wives of peers were ladies to royals in Tudor England. It was a wonderful opportunity, kept them busy, and at the center of court. Katherine’s sister, Anne, would serve all of Henry’s wives, including her. After the death of Lord Latimer, Katherine began a fling with the brother of former queen Jane Seymour, Sir Thomas Seymour. The two were most likely planning to be wed, but before the two could marry, Katherine would first catch the attention of King who quickly proposed.

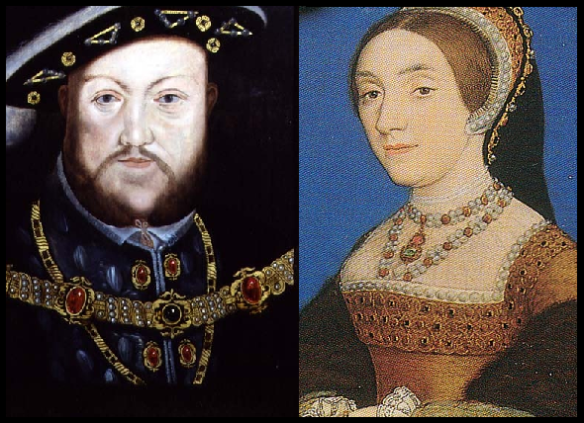

Lady Mary and Lady Elizabeth from the “Succession Portrait” which was commissioned while Katherine Parr was queen.

In spring before the wedding, Katherine would appear at court with both Lady Mary and Lady Elizabeth. The fact that the two had not been together earlier that spring and were now with Katherine and her sister at court was seen as significant. Katherine believed that a good relationship with the two was fundamental to her strategy. Once married, and confident as queen, she could develop the relationships further.

Katherine would go on to marry the King in July of that year. Within those who were present were the Ladies Mary and Elizabeth. With the marriage came three new step-children for Katherine to take care of. Instead of seeing it as her “duty”, she saw it as an opportunity as she had still not produced any children of her own.

Sources:

- Susan James. Catherine Parr: Henry VIII’s Last Love, The History Press, 2009.

- Linda Porter. Katherine the queen: The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII, MacMillan, 2010.

- Linda Porter. The Myth of “Bloody Mary”: A Biography of Queen Mary I of England, St. Martin Griffins, 2010.

- Anna Whitelock. Mary Tudor: England’s First Queen, Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2009.

17th-century plan of Boulogne, Fortified Places, by David Flintham.

17th-century plan of Boulogne, Fortified Places, by David Flintham. Letter from Katherine Parr to Henry VIII, July 1544. Extract from the letter: ‘God, the knower of secrets, can judge these words not to be only written with ink, but most truly impressed in the heart’. Queen Katherine Parr to King Henry VIII. in his absence, full of duty and respect, and requesting to hear from him. No date. . A Volume, containing Letters, &c. written by royal, noble, and eminent Persons of Great Britain, from the time of King Henry VI. to the reign of his present Majesty. These are originals, except where otherwise expressed. July 1544. Source: Lansdowne 1236, f.9.

Letter from Katherine Parr to Henry VIII, July 1544. Extract from the letter: ‘God, the knower of secrets, can judge these words not to be only written with ink, but most truly impressed in the heart’. Queen Katherine Parr to King Henry VIII. in his absence, full of duty and respect, and requesting to hear from him. No date. . A Volume, containing Letters, &c. written by royal, noble, and eminent Persons of Great Britain, from the time of King Henry VI. to the reign of his present Majesty. These are originals, except where otherwise expressed. July 1544. Source: Lansdowne 1236, f.9.