I love how much people dismiss Queen Kateryn Parr. There may be evidence that she WAS supposed to be Regent for Edward VI. See her signature AFTER Henry died.

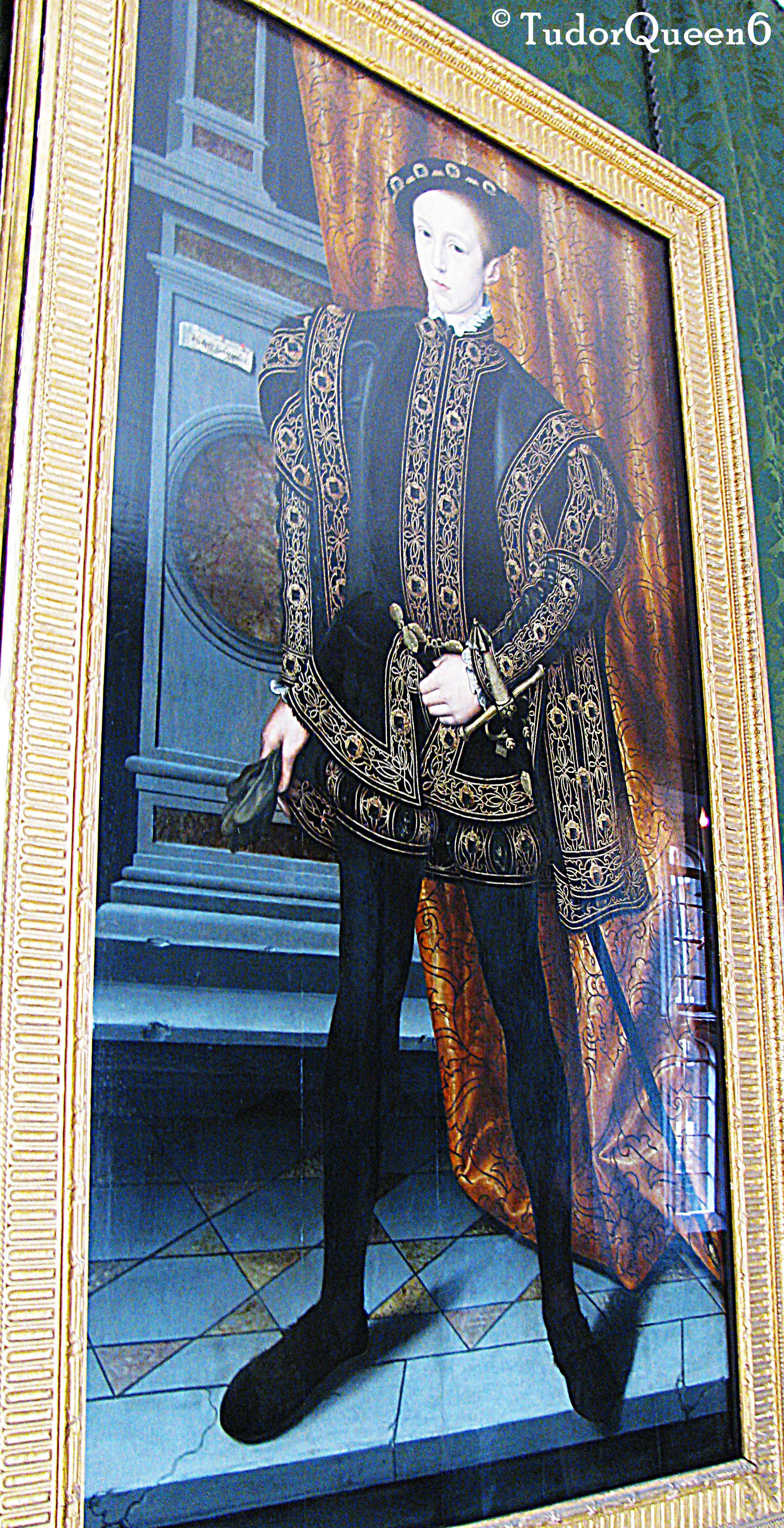

She was apparently signing as “Kateryn, the quene regente KP”. The theory goes that she was indeed made Regent for her stepson, King Edward VI. Which would make sense with the use of her signature. It is believed that Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, Kateryn’s brother the Marquess of Northampton, her brother-in-law the Earl of Pembroke and the council ousted her and rewrote the will. She would have made a wonderful Queen Regent. She proved she was capable of being Regent while Henry went to war with France. Perhaps she would have lived longer and prevented the succession from being rewritten. She gets credit for the placement of Princesses Mary & Elizabeth back into the line of succession behind their brother in 1545. That succession act seems to have overwritten or they disregarded King Edward’s will and supported the actual heir to the throne, Mary. Mary WAS the rightful heir. Jane was further down the approved line of succession. Why would you accept someone below the status of the actual daughters of King Edward’s father, Henry VIII? Kateryn Parr’s brother and brother in law were again involved in matters of the state and actually pulled off putting Lady Jane Grey on the throne for 9 days! Jane somehow outranked her own mother who was STILL alive and technically would have been the next heiress to the throne after Princesses Mary & Elizabeth. I never understood that. The Protestants feared the Catholic “Bloody Mary” (her nickname was started as Protestant propaganda, the pro Queen Elizabeth movement, lol) would try to return the country to the Pope and Catholicism. Mary was deeply religious. Kateryn Parr and Mary got on despite differences in matters like religion. Parr’s mother, Lady Maud, had served Mary’s own mother, Queen Katherine of Aragon, the first wife and crowned Queen consort to King Henry. The two women were pretty close. The Parrs backed Queen Katherine of Aragon when her lady in waiting became the Kings new obsession. Parr let Mary be and encouraged her every chance she could. One could argue she loved Mary more than Elizabeth. Heck, Kateryn named her only daughter and child, Mary, before the queen passed on 5 September 1548. Don’t think there were any other important Marys. The French Queen, Mary Tudor, had died long before Parr became Queen. Pretty sure it’s not after The Virgin Mary. Protestants aren’t that attached to her, right? I was raised Catholic, so I honestly don’t know. Anyway, Queen Kateryn Parr was VERY important. Read a book. She wasn’t an ex-queen. She remained Queen (consort) of England, Ireland, and France until she died. She was the LAST Tudor Queen Consort as King Edward died young. She was also the FIRST Queen of Ireland. Her funeral was the FIRST Protestant funeral for a Queen. Her mourner was none other than Lady Jane Grey, who would have probably stayed with Kateryn had the queen lived. Having Parr around seemed to pacify things. She knew how to handle tricky and dangerous situations. For Gods sake, she almost lost her head after she spoke with the King. It was overheard by the queens enemy, Bishop Gardiner, who saw an opportunity to “get rid” of Kateryn. I mean why not? He already KILLED TWO WIVES!! Lordy, so Gardiner tried to fuck with the Kings head. Saying shit like “it is a petty thing when a woman should instruct her husband” or some stupid sexist bs! Story goes, Kateryn was warned by an anonymous source who found her death warrant lying on the ground. YEAH RIGHT!! That’s straight up narcissistic abuse, my man!! Why do I feel like Henry set her up to test her loyalty? He was such a theatrical douche bag. No, no love for King Henry here. I have yet to see the film “Firebrand” which follows the reign of Kateryn as queen consort and queen Regente I believe. It’s based off Elizabeth Freemantle’s “Queen’s Gambit”. Anyway, Kateryn talked her way out of being arrested or worse by stroking the Kings ego and basically submitting to him just to fuvking survive. Imagine going through this marriage without psych meds like Benzos. I do believe they dabbled in potions however and she was known to “treat” melancholy with herbs from the gardens. Sudeley Castle where she is buried has a garden full of deadly herbs. Physic gardens. I have photos somewhere…

My page: Queen Catherine Parr

© 2024 Meg McGath. All research and original commentary belong to the author.

![The nursery and apartments of the dowager queen with Lady Anne Herbert standing by [the queen's sister] © Meg McGath, 2012.](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/sudeley1.png)