Warwick: You’re my prisoner, Edward!

Edward: I’m your King, cousin!

Warwick: Where did he go?

Elizabeth: Off with their heads!

Edward: No, I’ve decided to forgive them.

Elizabeth: Off with their heads!

Edward: I’m your King, wife!

Isobel: I’m still a pawn.

Gloucester: Shouldn’t I be taking a ring to Mount Doom?

Margaret Beaufort: I had sex. Didn’t enjoy it.

Elizabeth: I need a son, mother.

Jaquetta: Sorted.

Welles: I’m confused.

Jaspeer Tudor: You’re confused?!

Elizabeth: I want Warwick’s ship to sink, mother.

Jaquetta: Sorted.

Category Archives: The Family of Katherine Parr

The White Queen, episode 2

Elizabeth: Edward, Warwick hates you!

Edward: No, he loves me.

Warwick: No, she’s right. I hate you now.

Isobel: Anne! I’ve just found out I’m a pawn!

Henry VI: I could be wrong, but I think I might be Jesus.

Elizabeth: I’ve just been told my father’s dead.

Audience: So have we.

Margaret Beaufort: My son will be king!

Gloucester: Hang on, I’m pretty sure I just foreshadowed that I’ll be king.

Elizabeth: I’m going to put a curse on a bunch of people.

Audience. Knock yourself out. I think we’ve lost interest.

The White Queen, episode 1

Edward: I want you.

Elizabeth: You can’t have me.

Jaquetta: I see dead people.

Warwick: Edward!

Edward: Let’s get married. Secretly.

Elizabeth: Cool!

Anthony: He’s lying to you.

Elizabeth: No, he’s not.

Edward: No, I’m not.

Warwick: Edward!

Elizabeth: Curtsey, scum!

All I can do now is hope I get to catch the rest of it on youtube.

7 July 1517: St. Thomas Day Banquet at Greenwich

![Anonymous painting of Greenwich Palace during the reign of Henry VIII. [Wiki]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/greenwich_palace_anonymous.jpg?w=584) Anonymous painting of Greenwich Palace during the reign of Henry VIII. [Wiki]

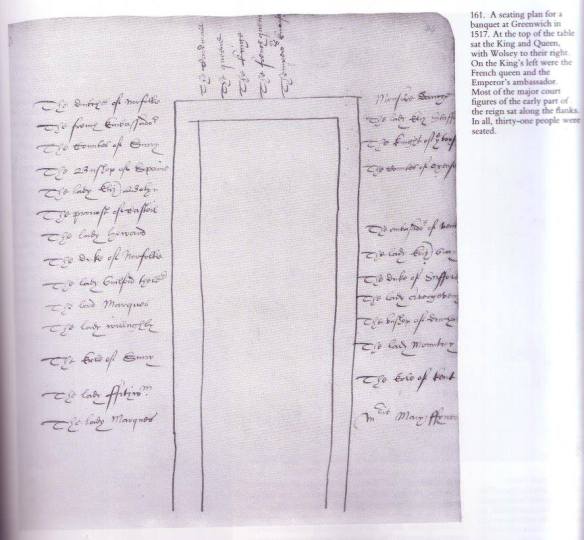

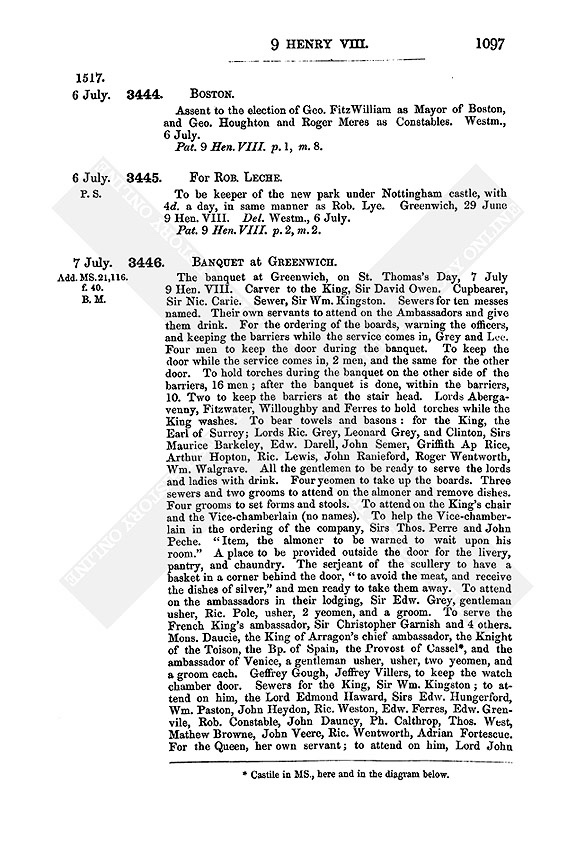

Anonymous painting of Greenwich Palace during the reign of Henry VIII. [Wiki]On 7 July 1517, a lavish banquet was held for the Emperor’s Ambassadors at Greenwich. The tables above show where several of the notables, including the King and Queen, sat. The banquet seems to have been largely a Howard family event.

The banquet was held on St Thomas’s day that is to say the summer feast the 7th of July. There were in all thirty three people seated at the banquet. The King had the centre place at the upper table; Queen Katherine was on his right and Cardinal Wolsey on hers; on the King’s left was the French Queen [Mary Tudor, Duchess of Suffolk] and the Emperor’s Ambassador was beside her. Then at the side tables with English peers and peeresses sat the Ambassadors of France, Aragon, and Venice. To attend on these thirty three persons no less than 250 names are given in a paper that was drawn up beforehand and these are almost all lords or knights. How they could avoid being in one another’s way is the difficulty. For instance Lords Abergavenny, Fitzwalter, Willoughby, and Ferrers to hold torches while the King washes. To bear towels and basons for the King the Earl of Surrey, Lords Richard Grey, Leonard Grey, and Clinton, Sir Maurice Berkeley, and eight other knights. The King’s server was Sir William Kingston and to attend on him Lord Edmund Howard [father of the future Queen Katherine] and fourteen knights the last named of whom is Sir Adrian Fortescue. To help the Vice-chamberlain in the ordering of the company, Sirs Thomas Perre and John Peche. At the third mess, the French Queen’s servant; to attend on him, Sirs William Parr [brother to Sir Thomas and uncle to the future queen] and several others.

Seating Chart of the banquet at Greenwich on St. Thomas Day, 1517. Thanks to my friend Katherine for this.

Seating Chart of the banquet at Greenwich on St. Thomas Day, 1517. Thanks to my friend Katherine for this.At the head table:

- Card

- Queen Katherine

- King Henry

- French Queen Mary Tudor

- Emperor’s Ambassador

The table on the left:

- Duchess of Norfolk

- French Ambassador

- Countess of Surrey

- Bishop of Spain

- Lady Elizabeth Boleyn [mother of the future Queen Anne]

- Provost of Cassel

- Lady Howard [mother of the future Queen Katherine]

- Duke of Nofolk

- Lady Guildford, the elder

- Lord Marques

- Lady Willoughby

- Earl of Surrey

- Lady FitzWilliam

- Lady Marques

The table on the right:

- Mons. Dancye

- Lady Elizabeth Stafford

- Knight of the Toyson

- Countess of Oxenford

- Ambassador of Venice

- Lady Elizabeth Gray

- Duke of Suffolk [Charles Brandon]

- Lady Abergavenny

- Bishop of Durham [perhaps Cuthbert Tunstall]

- Lady Montjoy

- Earl of Kent

- Mistress Mary Fynes [Mary Fiennes]

Sources

- ‘Henry VIII: July 1517, 1-10’, Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 2: 1515-1518 (1864), pp. 1092-1102. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=90948&strquery=william+parr Date accessed: 07 July 2013

- John S. Brewer, Robert H. Brodie, James Gairdner. Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII.:Preserved in the Public Record Office, the British Museum and Elsewhere: 1517 – 1518, Volume 2, Issue 2, H.M. Stationery Office, 1864.

- John Morris. The Venerable Sir Adrian Fortescue, knight of the bath, knight of St. John, martyr, Burns and Oates, 1887.

6 July 1483: The Coronation of King Richard III and Queen Anne

The night before the coronation, like monarchs before her, the Duchess of Gloucester stayed in The Tower of London.

For the procession from the Tower to Westminster on the eve of the ceremony, she wore a kirtle and mantle made from 27 yards of white cloth-of-gold furred with ermine and miniver, and trimmed with lace and tassels of white silk and gold (Laynesmith, p. 92).

Queen Anne

Queen AnneOn 6 July 1483, The Duke and Duchess of Gloucester were crowned King Richard III and Queen Anne of England. The couple shared a joint coronation. Not since the days of Edward II and Isabel of France had England seen such a magnificent event. The coronation day began at 7 am with a procession on foot from Westminster Hall to the Abbey. For that day, Anne dressed in a robe, curtle, “surcote overt”, and mantle, all of rich purple velvet, furred with ermine, and adorned with rings and tassels of gold; and another suit of crimson velvet, “furred with pure minever”. Her whole purple velvet suit had a fifty-six yard train. (Lawrance)

Both King and Queen had their own separate attendants and train. The Dowager Lady FitzHugh (born Lady Alice Neville) and her daughter, Lady Lovell (born Anne FitzHugh) along with the new Lady FitzHugh (born Elizabeth Burgh or Borough) were three of the seven noblewomen to ride behind the new Queen. Lady Elizabeth Parr (born Elizabeth FitzHugh) was also present. Lady FitzHugh was an aunt to Queen Anne and a cousin to King Richard. The Dowager Lady FitzHugh and Lady Parr were of course great-grandmother and grandmother to another queen consort, Katherine Parr. Both were dressed in fine dresses made by cloth that the King himself had given them. Lady Parr received seven yards of gold and silk while her mother received material for two gowns, one of blue velvet and crimson satin as well as one of crimson and velvet with white damask. As befitting of a Baroness, eight yards of scarlet cloth was given for mantles on the occasion. Lord Parr (Sir William Parr) chose not to attend the coronation despite being given a position as canopy bearer. Lord Parr had been a staunch supporter of King Edward IV through whom he rose.

In an attempt to conciliate with the Lancastrians, the trains of both the King and Queen were carried by the two lineal representatives of the house, the Duke of Buckingham and the Countess of Richmond (Lady Margaret Beaufort). (Lawrance)

An account from “The National and Domestic History of England“:

Queen Anne’s arms as Queen of England.

Queen Anne’s arms as Queen of England.After the procession of the king followed that of his Queen. The Earl of Huntingdon bore her sceptre, the Viscount Lisle the rod and dove, and the Earl of Wiltshire her crown. Then came the queen herself habited in robes of purple velvet furred with ermine having on her head a circlet of gold with many precious stones set therein. Over her head was borne a cloth of estate. On one side of her walked the Bishop of Exeter and on the other the Bishop of Norwich. A Princess of the blood, the celebrated Margaret, Countess of Richmond and mother of the future King Henry VII, supported her train. After the Queen walked the King’s sister Elizabeth, Duchess of Suffolk, having on her head a circlet of gold and after her followed a train of highborn ladies succeeded by a number of knights and esquires. Entering the Abbey at the great west door the King and Queen took their seats of state staying till divers holy hymns were sung when they ascended to the high altar where the ceremony of anointing took place. Then the King and Queen put off their robes and there stood all naked from the middle upwards and anon the Bishop anointed both the King and Queen. This ceremony having been performed, they exchanged their mantles of purple velvet for robes of cloth of gold and were solemnly crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury assisted by the other bishops. The Archbishop subsequently performed high mass and administered the holy communion to the King and Queen after which they offered at St Edward’s shrine where the king laid down King Edward’s crown and put on another and so returned to Westminster Hall in the same state they came.

Richard III with his queen Anne and son, Edward, Prince of Wales.

Richard III with his queen Anne and son, Edward, Prince of Wales.The banquet, which took place at four o clock in the great hall, is described as having been magnificent in the extreme. The king and queen were served on dishes of gold and silver. Lord Audley performed the office of state carver. Thomas Lord Scrope that of cupbearer. Lord Lovel, during the entertainment, stood before the king, “two esquires lying under the board at the king’s feet.” On each side of the queen stood a countess with a plaisance or napkin for her use. Over the head of each was held a canopy supported by peers and peeresses. The guests consisted of the cardinal archbishop the lord chancellor, the prelates, the judges, and nobles of the land, and the Lord Mayor, and principal citizens of London. The ladies sat by themselves on both sides of a long table in the middle of the hall. As soon as the second course was put on the table, the king’s champion Sir Robert Dymoke rode into the hall; his horse being trapped with white silk and red and himself in white harness the heralds of arms standing upon a stage among all the company. Then the king’s champion rode up before the king asking all the people if there was any man would say against King Richard III why he should not claim the crown. And when he had said so all the hall cried King Richard with one voice. And when this was done anon, one of the lords brought unto the champion a covered cup full of red wine and so he took the cup aud uncovered it and drank thereof. And when he had done anon he cast out the wine and covered the cup again and making his obeisance to the king turned his horse about and rode through the hall with his cup in his right hand and that he had for his labour. Then Garter king at arms supported by eighteen other heralds advanced before the king and solemnly proclaimed his style and titles. No single untoward accident marred the harmony or splendour of the day. When at length began to close the hall was illuminated by great light of wax torches and cressets apparently the signal for the king and queen to retire. Accordingly wafers and hipocras been previously served Richard and his rose up and departed to their private apartments in the palace. (Aubrey)

Aneurin Barnard as King Richard III and Faye Marsay and Queen Anne. Fictional portrayal in Philippa Gregory’s “The White Queen” (2013).

Aneurin Barnard as King Richard III and Faye Marsay and Queen Anne. Fictional portrayal in Philippa Gregory’s “The White Queen” (2013).Sources

- William Hickman S. Aubrey. “The National and Domestic History of England,” 1878. pg 193-4.

- Hannah Lawrance. “Historical Memoirs of the Queens of England from the Commencement of the Twelfth Century,” Volume 2, Moxon, 1840.

Nonsense about Ladies Isabel and Anne Neville

Lady Anne (Faye Marsay) and Lady Isabel (Eleanor Tomlinson) in “The White Queen”.

“To anyone who has any interest in these two women: Please stop writing about Isobel and Anne Nevill as if they were weak women who had no control over their lives. Please stop using their early deaths as a sign that they were Doomed From the Start. Please read something about their father. (Both Hicks and Pollard have done a bang up job here.) Oh, and can we consign the overused, tired and meaningless word pawn to the dustbin of history? Let’s stop the nonsense. It’s starting to get depressing.”

To those of you watching “The White Queen”, please take some time to read this blog about THE REAL Ladies Isabel and Anne. You would be surprised that they are NOTHING like the show has portrayed them. They also didn’t constantly get b’ed out by the queen.

I stumbled on this while I was on the hunt for information for an upcoming post.

I feel that it needs a response, something to balance the books a little. I know, it’s an uphill battle – the view that poor Isobel and Anne were mere pawns (oh, and Doomed) is so entrenched that it’s going to take a miracle to shift it by so much as a millimetre.

Just to set the tone, here are some of the words used to described Warwick and/or his actions:

”political conniving”; “charismatic”; “self-centered”; “arrogant”; “man of moderate military skill”; “merciless”; “exploit”; “had no need to hold [his daughters] in esteem”; “hankering for supremacy and clout”; the only loyalty he held was to himself”; “enmesh in his pursuit for power”; “ego”; “narcissism”; “heedless”; “used his youngest daughter”; “spider web of intrigue”; “hopeless machinations”; “fanaticism for prestige and importance”.

Phew!

Now for the…

View original post 1,712 more words

Family of Queen Katherine: Lady Margaret, Countess of Oxford

Redrawn effigy of John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford and Lady Margaret before it was destroyed; original illustration was by Daniel King, Colne Priory Church, destroyed c. 1730.

Redrawn effigy of John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford and Lady Margaret before it was destroyed; original illustration was by Daniel King, Colne Priory Church, destroyed c. 1730.Margaret Neville, Countess of Oxford (c.1443[1]-after 20 November 1506/1506[1][2]) was the daughter of Sir Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury and Lady Alice [Montague], suo jure 5th Countess of Salisbury [in her own right]. Margaret was born in her mother’s principal manor in Wessex.[1] She was the last of six daughters and ten children.[1] Margaret’s godmother and namesake may have been after Margaret Beauchamp (1404 – 14 June 1468), eldest daughter of Sir Richard Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick and his first wife Elizabeth Berkeley. Beauchamp was wife to John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury [a brother to Mary Talbot, Lady Greene, the maternal 3x great-grandmother to Queen Katherine Parr and thus a 4x great-uncle]. Margaret Talbots’s sister, Anne, suo jure 16th Countess of Warwick would marry Margaret Neville’s brother, Richard, and he would inherit Anne’s title through marriage making him the 16th Earl of Warwick.

The Neville family was one of the oldest and most powerful families of the North. They had a long standing tradition of military service and a reputation for seeking power at the cost of the loyalty to the crown as was demonstrated by her brother, the Earl of Warwick.[5] Warwick was the wealthiest and most powerful English peer of his age, with political connections that went beyond the country’s borders. One of the main protagonists in the Wars of the Roses, he was instrumental in the deposition of two kings, a fact which later earned him his epithet of “Kingmaker”.

By her paternal grandmother, Lady Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland, Margaret was the great-great-granddaughter of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. Lady Joan Beaufort was the legitimized daughter of Prince John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and Aquitaine, and his mistress, later wife, Katherine Roët Swynford. As such, Margaret was a great-niece of the Lancastrian King Henry IV. Margaret’s paternal grandfather was Sir Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland, the second husband of Lady Joan. One of their daughters (Margaret’s aunt), Lady Cecily, became Duchess of York and mother to the York kings, Edward IV and Richard III. Margaret’s mother, Lady Salisbury, was the only child and sole heiress of Sir Thomas Montacute, 4th Earl of Salisbury by his first wife Eleanor Holland [both descendants of King Edward I]. Margaret’s grandmother, Lady Eleanor, was the granddaughter of Princess Joan of Kent, another suo jure Countess (of Kent) and Princess of Wales. Princess Joan was of course the mother of the ill-fated King Richard II making Eleanor Holland his niece. Princess Joan herself was the daughter of Prince Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent; son of Edward I by his second wife, Marguerite of France.

Margaret married to John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford, the second son of John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford, and Elizabeth Howard. Oxford was one of the principal Lancastrian commanders during the English Wars of the Roses. Margaret was the last of the sisters to marry. It was her brother, Warwick, who secured the marriage between Margaret and Oxford.[3] Margaret had 1000 marks to offer as a dowry which had been settled upon her in her father’s will in 1460. The financial gain for Oxford was important, but with Margaret he gained a whole family of political advantage; as Margaret was the sister of Warwick. Oxford’s family had been on the Lancastrian side. His father had been executed after trying to replace Edward IV with Henry VI.

At the battle of Bosworth and Stoke, Oxford is recorded as fighting beside the Stanleys’ (husband and son of Oxford’s sister-in-law, Eleanor Neville) on behalf of the House of Lancaster.

As for the wives of rebels, Richard III did indeed give the Countess of Oxford, Margaret Neville, £100, but this was a continuation of a grant from Edward IV, who is not given any particular credit for generosity. In any case, as David Baldwin notes, Richard had been given the Earl of Oxford’s estates following the Battle of Barnet and could presumably afford to part with £100. Back in the 1470′s, the young Richard had bullied Margaret Neville’s mother-in-law, Elizabeth de Vere, the dowager Countess of Oxford, into giving him her own estates for an inadequate consideration, but this inglorious episode doesn’t find its way into Kendall’s biography.

Sources:

- David Baldwin. The Kingmaker’s Sisters: Six Powerful Women in The War of the Roses, Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2009.

- Douglas Richardson. “Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families,” 2nd Edition, 2011. p. 274. (“She was living 20 Nov. 1506.”)

- Anne Crawford. “The Yorkists: The History of a Dynasty,” Continuum International Publishing Group, Apr 15, 2007. p. 78, 98, 108.

- James Ross. “John de Vere, Thirteenth Earl of Oxford (1442-1513): The Foremost Man of the Kingdom,” Boydell Press, Mar 17, 2011. p. 51.

- Linda Porter. “Katherine the Queen; The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII,” Macmillan, 2010.

The White Queen: romance, sex, magic, scowling, social snobbery and battles

“The White Queen: romance, sex, magic, scowling, social snobbery and battles” by Amy Licence

How important is authenticity when filming historical dramas?

Terribly important! You should see the notes I sent to the series producers waxing lyrical about the use of horses, clothes, how people travelled, and so on. That sort of thing really matters. However, there are a number of compromises you do have to make when working in film, which can be very frustrating – that’s why I’m a novelist, I suppose.Historical fiction, when written well, can teach you these things without you having to study it. (Philippa Gregory, BBC History Magazine Interview)

“It is a little more Romeo and Juliet than accurate medieval protocol.” (Licence)

Sunday nights episode of ‘The White Queen’ in my opinion was great. Put a woman screenwriter together with the BBC and bam! However there was something that really made me angry about the episode and surprise, surprise — I’M NOT THE ONLY ONE who had a problem with it.

Amy Licence, author of the latest biography of Queen Anne Neville and Elizabeth of York reviewed the first episode. Licence and I agree on this both — she basically sums up that they (screenwriter or Gregory herself) REALLY screwed up on behalf of Lady Cecily Neville, Duchess of York (grandaunt of Anne Neville); thank you Lord!

“It was in the exchange with Duchess Cecily (Caroline Goodall) however, that Jacquetta, as her daughter’s mouthpiece, really overstepped the historical mark. The disapproving Duchess, who was known in real life as “proud Cis,” is too easily overcome by her social inferiors when they whip out her apparent “secret” affair with a French archer. Lost for words, she is silenced within minutes, almost cowed by them. While contemporary notions of “courtesy” dictated extreme forms of submission to the queen, this is a Cecily straight from the pages of a novel rather than the actual proud aristocrat who asserted her own right to rule.”

I’m going to be brutally honest here — are you kidding me?? I don’t like Jacquetta’s “holier than thou” attitude that is emerging. This was obviously a horrid and tasteless attempt to boost Jacquetta’s influence and “power” over the Duchess. It’s more than obvious that Gregory has become obsessed with Jacquetta and her daughter. In my opinion, if they REALLY wanted to boost Jacquetta SO much — they could have done it in a different way. They didn’t have to insult the King’s mother, the daughter of a powerful Earl and Countess Lady Joan Beaufort, granddaughter of a royal Duke of Lancaster and titular King of Castile [son of King Edward III of England], and widow of the Duke of York [double descendant of Edward III]! I know it didn’t happen in history, but still — that scene should have been cut or done differently. If they had been at court and the Duchess had been sitting with her son, I do not think the two would have addressed each other as such and Elizabeth wouldn’t have pulled the Queen card after letting her mother b***h out her mother-in-law. It’s rather ironic that Elizabeth comes in flabbergasted, but after her mother calls her mother-in-law a whore she has the nerve and guts to demand the Duchess bow down to her; then gloats to her husband how everyone is “great friend’s” now. Yeah, sure — Elizabeth is now best friends with “Duchess Cecily”. I don’t think Gregory thought about court etiquette when writing these books and whoever approved the scene has not read any history books lately.

“James Frain, recently lauded for his performance as Thomas Cromwell in The Tudors, may well emerge to steal the show alongside Margaret Beaufort and the other York brothers…” Even Licence applauds Lady Margaret Beaufort early on.

For the complete review — http://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2013/06/white-queen-romance-sex-magic-scowling-social-snobbery-and-battles

Jacquetta of Luxembourg and the Dukes of Burgundy?

Since the beginning of Philippa Gregory’s obsession with the Woodville family and Jacquetta of Luxembourg, she has claimed that Jacquetta was descended from the Dukes of Burgundy. For the past few weeks I have been trying to find a link to what she might be talking about. Jacquetta’s tree doesn’t show any connection or descent from the Dukes of Burgundy since before .. well .. I’m still looking back past the 1100s.

OK… I think I found what they are talking about; two explanations and a HUGE stretch.

Theory One — Bedford’s Wives

Remember “The Tudors” brilliant idea of lumping King Henry VIII’s sisters in to one character? Perhaps Philippa Gregory and the writer Emma Frost are doing the same; two historical characters compiled in to one. Here’s how it works: Jacquetta was married to the Lancastrian Duke of Bedford. Bedford’s FIRST wife, Anne of Burgundy, was from Burgundy; the daughter of John II, Duke of Burgundy. Anne’s brother was Philip “the Good”, Duke of Burgundy and father of Charles, the Bold, who was featured in the second episode of “The White Queen” as “cousin” to Jacquetta. A year after the death of Anne of Burgundy, Bedford remarried to Jacquetta, but faced opposition for various political reasons in this decision from Anne’s brother the Duke of Burgundy.[1][2] From this time on, relations between the two became cool, culminating in the 1435 peace negotiations between Burgundy and Charles VII, the exiled king of France. Later that year, a letter was dispatched to Henry VI, formally breaking their alliance.[2]

The series doesn’t mention the fact that Jacquetta was married to the Duke of Bedford – she is *just* a powerful noblewoman related to the Dukes of Burgundy which is not really the case as I will explain. The series chose to omit that the Duke of Bedford existed and married Jacquetta, and Jacquetta in my opinion is seen as a mix of two historical women – Anne of Burgundy, Bedford’s first wife, and Jacquetta of Luxembourg.

Theory Two — Taranto Relations

Second possible explanation Jacquetta’s grandfather, the Duke of Andria (Francesco del Balzo) married Marguerite of Taranto whose mother was Empress Catherine of Constantinople, daughter of Charles, Count of Valois (4th son of Philip III of France, brother to the 2nd queen consort of Edward I of England, Marguerite of France and uncle to queen consort Isabel of France of Edward II of England).

Francesco and Marguerite had two kids that produced NO surviving issue! Any who, Empress Catherine (of Valois) was a paternal sister to Philip VI of France (son of Charles of Valois and his first wife, Margaret, Countess of Anjou). Philip VI married Joan of Burgundy, daughter of Robert II, Duke of Burgundy. In 1361, Joan’s grandnephew, Philip I of Burgundy, died without legitimate issue, ending the male line of the Dukes of Burgundy. The rightful heir to Burgundy was unclear: King Charles II of Navarre, grandson of Joan’s elder sister Margaret, was the heir according to primogeniture, but John II of France (Joan’s son) claimed to be the heir according the proximity of blood. In the end, John won.

So Jacquetta wasn’t related to them at all by my calculations; only by marriage. Her half-uncle (James of Baux) died in 1383 and her half-aunt (Antonia, Queen of Sicily) died in 1373. They were the only blood connection to the Dukes of Burgundy as cousins. Jacquetta wasn’t born until 1416 — so there would be no close connection.

Other Possible Theory — Henry V of Luxembourg

However, there is a stretch here — Bonne of Bohemia [of Luxembourg] was the mother of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, himself the great-grandfather of Charles the Bold. Bonne of Bohemia was the great-great-granddaughter of Henry V, Count of Luxembourg. Jacquetta herself was a 5x great-granddaughter of Henry V. Funny thing being — anyone who descended from King Edward III of England [most to all of the nobility at court and royal houses of Europe by the reign of King Edward IV] descended from Henry V of Luxembourg via his great-granddaughter, Philippa of Hainault, queen consort to Edward III of England. Included in that long list are Queens Katherine of Aragon, Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleves, and Katherine Parr [wives 1,3,4, and 6 of King Henry VIII of England].

So using that connection, Jacquetta and Charles would have been at the closest 6th cousins, once removed. Where as the King’s mother, Cecily [Neville], was a 1st cousin, once removed of the Duke. Cecily’s mother, Lady Joan Beaufort [daughter of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster], was a grandaunt of Charles of Burgundy. So who are we kidding when it comes to the show — we saw the King’s mother treated rather poorly [imo extremely] while Jacquetta was positioned as a high born noblewoman with close connections to Burgundy and what not. Wiki [not a good source] even tried to pull that Jacquetta was cousin to Sigismund of Luxembourg, the Holy Roman Emperor (1368–1437); that her first marriage to the Duke of Bedford [John of Lancaster, a younger son of the first Lancastrian King, Henry IV] was

“to strengthen ties between England and the Holy Roman Empire and to increase English influence in the affairs of Continental Europe.”

Portrait of Emperor Sigismund, painted by Albrecht Dürer after the emperor’s death [Source: Wiki]

To add to the distance between Jacquetta and the Holy Roman Emperors — the second Luxembourg Holy Roman Emperor, Sigismund, had only one child; a daughter. Elisabeth of Luxembourg was the only child of the Emperor and his second wife and consort, Barbara of Cilli. When Sigismund died in 1437, Elisabeth was expected to ascend to her father’s thrones, but her rights were ignored and the titles of King of Germany, Hungary, and Bohemia was passed to Elisabeth’s husband Albert V, Duke of Austria. The title of Holy Roman Emperor was passed to the House of Habsburg [Philip the Bold would marry Juana I of Castile, sister of Queen Katherine of Aragon] where it would stay for three centuries [1440-1740]. Frederick V, Duke of Austria would become Frederick III of the Holy Roman Empire. After only two Emperors from the House of Luxembourg, the title was passed to the Habsburg dynasty where it would remain until 1740 upon the death of Charles IV. Charles, like Sigismund, had only one surviving daughter. Maria Theresa, was obviously denied her rights to succeed as Holy Roman Empress because she was a woman. Her father, Charles IV, was succeeded by Charles VII of the House of Wittlesbach. Charles VII ruled until his death in 1745. It was then that Maria Theresa’s husband was elected as Holy Roman Emperor and she became his consort. The House was now called Habsburg-Lorraine.

Note

In the show, the marriage of Edward’s sister, Margaret of York, is hinted to be due to Jacquetta’s relations. Margaret of York would marry Charles as his third wife on 27 June 1468. They had no issue, but Margaret was a wonderful stepmother to her husband’s children.

Sources

- Chipps Smith, Jeffrey (1984). “The Tomb of Anne of Burgundy, Duchess of Bedford, in the Musée du Louvre“. Gesta 23 (01): 39–50.

- Weir, Alison (1996). “The Wars of the Roses: Lancaster and York“. London: Ballantine Books.

7 June 1520: The Field of the Cloth of Gold

The Field of the Cloth of Gold started on 7 June 1520. It took place between Guînes and Ardres, in France, near Calais, from 7 June to 24 June 1520. It was a meeting arranged to increase the bond of friendship between King Henry VIII of England and King Francis I of France following the Anglo-French treaty of 1514.

“The Field of the Cloth of Gold” British School, 16th century (artist) c.1545 (Royal Collection under Wiki Commons)

Among those present was the widowed Lady Maud Parr and 1 woman; Lady Joan Guildford the elder (Joan Vaux, sister of Katherine Parr’s uncle-in-law AND step-grandfather Sir Nicholas, Lord Vaux of Harrowden) and 2 gentlewomen; Lady Vaux (most likely Catherine’s maternal aunt, Anne Green (d.1523)) and 1 woman; and Lady Mary Parr (Mary Salisbury, wife of Katherine’s uncle, William, Lord Parr of Horton) and 1 woman. These women accompanied and attended the queen, Katherine of Aragon.