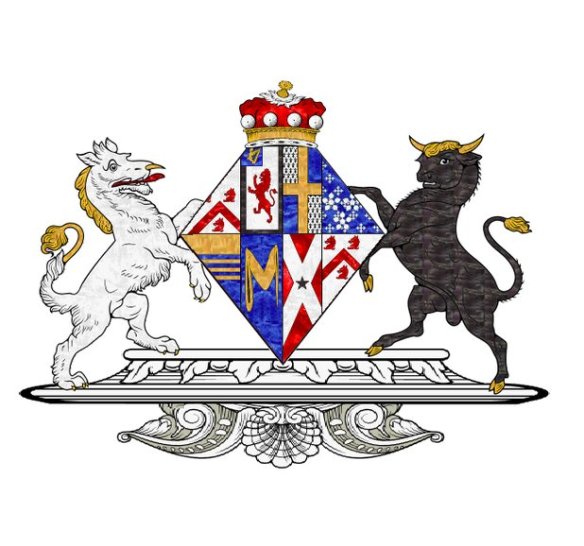

![Katherine Parr and Anne Boleyn, both were of equal birth -- Katherine's lineage, especially that of her father however, was better and more established at court than the Boleyn's. [David Starkey]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/kat_anne.png?w=584)

Katherine Parr and Anne Boleyn, both were of equal birth — Katherine’s lineage, especially that of her father however, was better and more established at court than the Boleyn’s. [David Starkey]

We have had this discussion before; who has the better lineage, who’s family was more “noble”, who was born “higher”, etc. Online, in the Wikipedia article for Anne Boleyn, it states that:

“According to Eric Ives, she was certainly of more noble birth than Jane Seymour, Catherine Howard, and Catherine Parr, Henry VIII’s three other English wives.”[19]

When you look at the actual source listed on Wikipedia, [19], it states Eric Ives’s opinion that “She [Anne] was better born than Henry VIII’s three other English wives.”

Ives’s statement is preceded by who Anne Boleyn’s great-grandparents were, “[apart from Geoffrey Boleyn], a duke, an earl, and the granddaughter of an earl, the daughter of one baron, the daughter of another, and and an esquire [on the path to becoming a knight] and wife.” However, when Boleyn was born, her grandfather was not a Duke. He was only Earl of Surrey. In fact, up until a few days ago, the wife of the eventual 3rd Duke of Norfolk, Princess Anne of York (daughter of Edward IV) was labeled incorrectly on Wikipedia as “Countess of Surrey.” See below, “Dukedom of Norfolk“.

I think what is in the Wikipedia article is rather misleading and a false statement. If they are going to quote Ives, they should use the actual quote. However, both historians Agnes Strickland and Dr. David Starkey have a different view on Katherine Parr’s lineage and “lower birth than Anne Boleyn.” Agnes Strickland quotes that Katherine Parr’s paternal ancestry was more distinguished than that of Thomas Boleyn and John Seymour. According to David Starkey, Katherine Parr’s lineage,

“unlike that of Henry’s second wife, Anne Boleyn, was better and more established at Court.”[4]

The Wiltshire Archeological and Natural History Magazine (Vol. 18, 1879), also states,

“She was of more distinguished ancestry than either Anne Boleyn or Jane Seymour.” (pg 85)

The “noble” birth I suppose refers to the fact that her mother was a “Lady” as a daughter of a Duke? That was her maternal lineage and Boleyn’s mother, at the time of her birth, was not the daughter of a Duke, but the daughter of an Earl. Anne Boleyn’s cousin Queen Katherine Howard, was the daughter of Lord Edmund Howard (as styled after 1514), a male line of the Dukes of Norfolk. In 1480, (Elizabeth Howard’s birth date that I have) the Howard family was not Duke of Norfolk; not even Earl of Surrey. After John Howard’s (great-grandfather of Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard) elevation to Duke on 28 June 1483, his son, Thomas (later 2nd Duke and father to Elizabeth Howard), was created Earl of Surrey on the same date. However, the titles were forfeited and attained after the Battle of Bosworth field and the death of King Richard III (1485). The “2nd Duke” (grandfather to Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard) was restored as Earl of Surrey in 1489 (under Henry VII); and restored/created the (2nd) Duke of Norfolk in 1514 (under Henry VIII), and resigned the Earldom of Surrey to his son (also named Thomas, future 3rd Duke) on the same day; the future “3rd Duke” wouldn’t become Duke until the death of his father in 1524. Boleyn and Howard were married c.1500 while Elizabeth’s father was still Earl of Surrey. The Howard family had no idea if Surrey would be granted the Dukedom again (1489-1514 is a big gap and there were two different monarchs reigning, Henry VII and then Henry VIII in 1509). Therefore, when Anne was born — she was not the granddaughter of a Duke.

“Duke of Norfolk“

History lesson on the Howard’s — the Howard’s were not always the Dukes of Norfolk and in fact, the title was forfeited several times; in 1485, 1546, and 1572.[1] The title was inherited by Anne and Katherine’s ancestor Sir John Howard, the son of Thomas Mowbray’s [created Duke of Norfolk in 1397] elder daughter Lady Margaret Mowbray, Lady Howard (wife of Sir Robert Howard). Sir John Howard was created 1st Duke of Norfolk on 28 June 1483, in the title’s third creation. However, two years later, the title, along with the courtesy title of Earl of Surrey, was forfeit and attained upon his death at the Battle of Bosworth, 22 August 1485.[2]

When the title Duke of Norfolk was created for Thomas Mowbray on 1397, it was most likely bestowed upon him due to his mother, Elizabeth Segrave (1338-1399), eldest surviving daughter of Princess Margaret of England, suo jure 2nd Countess of Norfolk.

Interesting fact, Katherine Parr’s great-great-grandfather, Sir Thomas Tunstall, would re-marry to Hon. Joan Mowbray (Parr’s 2nd cousin, 5x removed), sister of the 1st Mowbray Duke of Norfolk. Although they had no issue the Tunstalls’ and the children of Joan by her first husband Sir Thomas Grey grew up together.

The title would descend from Mowbray’s eldest son, John Mowbray, the 2nd Duke of Norfolk [not an ancestor to the Howard Dukes of Norfolk]. The title would hold in the Mowbray family until the death of Mowbray’s great-great-granddaughter, Lady Anne Mowbray, 8th Countess of Norfolk (d.1481); who died without issue. Upon her death, her heirs normally would have been her cousins William, Viscount Berkeley (descendant of the 2nd Duke’s sister, Lady Isabel Mowbray) and John, Lord Howard (descendant of the 2nd Duke’s other sister, Lady Margaret Mowbray), but by an act of Parliament in January 1483 the rights were given to her husband Richard of Shrewsbury [Prince in The Tower], with reversion to his descendants, and, failing that, to the descendants of his father Edward IV.[8] This action may be a motivation for Lord Howard’s support of the accession of Richard III. He was created Duke of Norfolk and given his half of the Mowbray estates after Richard’s coronation on 28 June 1483.

After John Howard’s elevation to Duke, his son, Thomas, was created Earl of Surrey on 28 June 1483.[3] The titles were forfeited and attained after the Battle of Bosworth field. The “2nd Duke” (grandfather to Queen Anne Boleyn and Queen Katherine Howard) was restored as Earl of Surrey in 1489; and restored as the 2nd Duke of Norfolk in 1514, and resigned the Earldom to his son (also named Thomas) on the same day. Howard (later 3rd Duke of Norfolk) had been previously married to Anne of York, daughter of King Edward IV. As a sign of closeness between King Richard III and the Howard family, Anne was betrothed to Thomas Howard in 1484.[10] At the time of their marriage in 1494/95, Howard had no titles and wasn’t even knighted (knt. 1497) which was very unusual for a marriage to a Princess. As Princess of England, Anne had been previously contracted to marry Philip “the handsome”, future Duke of Burgundy (later Philip I of Castile as husband to Juana I of Castile, sister of Katherine of Aragon). On the death of her father in 1483, the marriage however, never took place. Therefore, Anne who died in 1511, was never Countess, but technically Anne of York, Lady Howard (Lady Anne Howard).[11]

As stated above, the former Earl of Surrey (later 2nd Duke) wasn’t created Duke of Norfolk until 1 Febraury 1513/14, 4/5 years after the death of Henry VII.[3] The title would again be forfeited after the arrest of the 3rd Howard Duke of Norfolk and his son Henry, Earl of Surrey during Queen Katherine Parr’s reign, 1546.[3] At this point in time, the Parr’s and Seymour’s thrived while the Howard’s fell from favor. The title was restored to Henry Surrey’s son who became the 4th Duke in 1554 under the Catholic Queen Mary [his father predeceased him] who’s title was also forfeited upon his execution on 2 June 1572. The most interesting thing here being that Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey had been brought up in the house of Henry Fitzroy, natural son of Henry VIII with Katherine’s brother, William Parr. The two were obviously more than acquainted and most likely good friend’s. There must have been some mixed feelings with the execution of Surrey.

“although she be a simple maid, having but a knight to her father, yet she is descended of right noble blood and parentage. As for her mother, she is nigh of the Norfolk’s blood, and as for her father, he is descended of the Earl of Ormonde, being one of the Earl’s heirs general.” (A letter from Lord Percy declaring Anne’s family was on the “same” level as his; from Ecclesiastical biography, ed. Christopher Wordsworth, p. 590. [5])

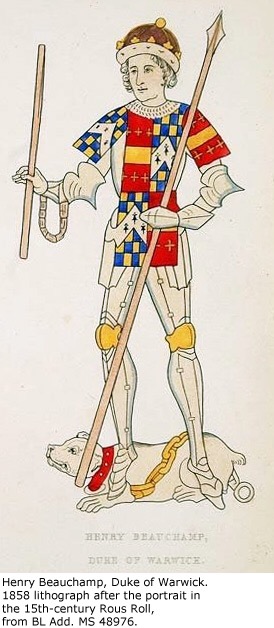

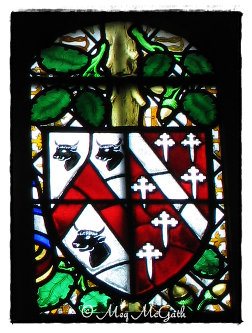

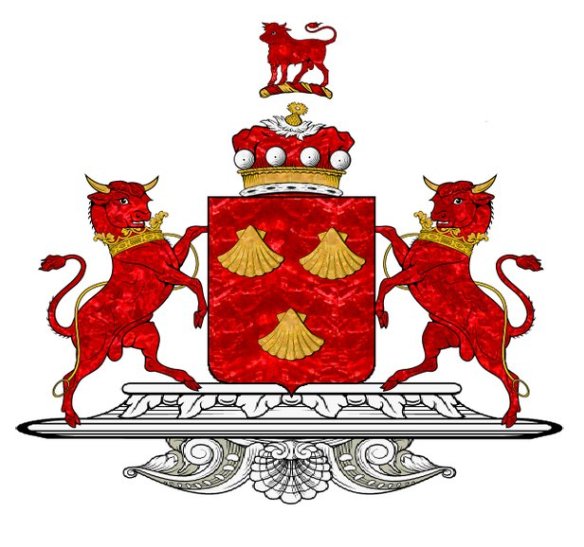

Butler, Earl of Ormonde. The 1st and 4th quarters were used “illegally” in the arms of Anne Boleyn as Marquess of Pembroke and Queen of England. European Heraldry

One can only conclude that Lord Percy was so in love with Anne that he would have done anything to help her succeed. Wordsworth online at Open Library also tells the story put forth about Anne and how she was styled Anne Rochford on her papers for Marquess of Pembroke. It seems that Anne Boleyn was doing everything against the rules of the society she lived in. Anne couldn’t use ‘Rochford’ as a surname – her mother should have used this title, as Jane Parker did when George Boleyn became ‘Viscount of Rochford’.

Anne’s paternal GRANDMOTHER, Lady Margaret Butler, was not an heiress to the Earldom of Ormonde being a female; therefore Thomas Boleyn [NOT Butler] was not “the Earl’s heirs general.” Earldom’s DID NOT pass through women; a woman could be created a Countess, but that title would have been created solely for that woman and her male heirs, like the “Marquess of Pembroke.” Perhaps if Lady Margaret had been the only child of the 7th Earl, the title would have passed to her and through her, but she was not the only child and according to law her male Butler relatives [cousins] would have inherited that title BEFORE her as Piers Butler did. After the death of the 7th Earl in 1515, Piers assumed the title as it was only heirs MALE that could inherit the title, not women (unless under special circumstances by orders of Parliament)!

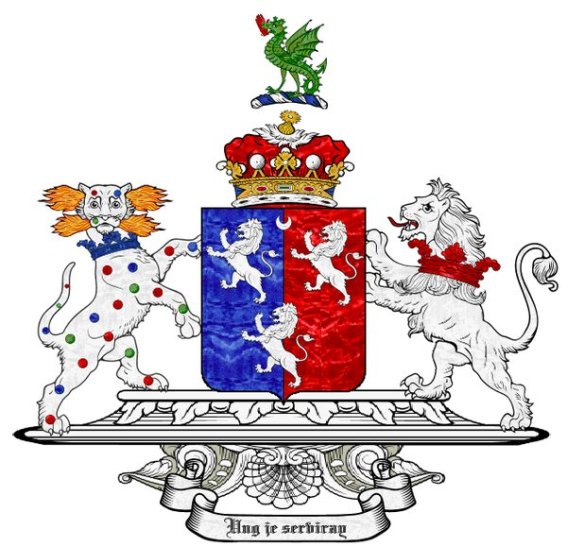

Tomb of Sir Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormonde and Lady Margaret Fitzgerald, parents to the 9th Earl. Saint Canices Cemetery, Kilkenny County, Kilkenny, Ireland.

Concerning Thomas Boleyn’s claim to the Earldom of Ormonde:

In 1529, Piers Butler was forced to give up the title of 8th Earl of Ormond, which he assumed in 1515 and the title was granted to Sir Thomas Boleyn. In place of the Earldom of Ormonde, Piers received the title of Earl of Ossory instead; the subsidiary title held by the Earls of Ormond.

Why would the King force Piers to give his title up? At that time, Henry VIII was already romantically involved with Anne Boleyn and the answer is clear – Thomas received Earldom of Ormond due to Anne’s relationship with Henry VIII. That Boleyn owned the title of Earl of Ormond to his daughter’s influence, is proved by him losing the title after Anne’s execution – in May 1536 the Irish Parliament passed the act that reverted Butler lands and the title of Earl of Ormond to the Crown. Henry VIII finally granted the Earldom of Ormond to Piers Butler in October 1537 (Starkey states early February 1538 [9]), before Boleyn’s death. The Earldom of Ormond was bestowed upon Thomas Boleyn without lawful claim in 1529 according to common law.

What about the Earldom of Wiltshire that Thomas received the same year?

The title of 1st Earl of Wiltshire was held by Henry Stafford, a brother of the 3rd Duke of Buckingham, executed in 1521, and an uncle of Elizabeth Stafford who married Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk in 1513. Henry Stafford died without a male issue in 1523 and the title of Earl of Wiltshire expired with his death. The title was vacant until 1529 when Thomas Boleyn received both titles – the Earl of Ormond and Wiltshire. Why would Henry VIII bestow the title of Earl of Wiltshire upon Thomas Boleyn?

In the past, the title of Earl of Wiltshire was held by James Butler, 5th Earl of Ormond. Thomas Boleyn’s claim to the Earldom of Wiltshire was the result of his claim to the Earldom of Ormond due to his affinity with the Butler family from his mother’s side. This raises a question – if the title of the Earl of Wiltshire was vacant from 1523, why did Thomas Boleyn receive it as late as in 1529? It is reasonable to assume that Anne Boleyn influenced the King to elevate her father to such honour.

(p.62,63 [6])

![Sir James Butler, 9th Earl of Ormonde, son and heir of Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormonde [the rightful heir to the Earldom]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/butler-earl-of-ormonde.jpg?w=584)

- Sir James Butler, 9th Earl of Ormonde, son and heir of Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormonde [the rightful heir to the Earldom]. The identification comes after a study by David Starkey.[9]

There were very few women who inherited Earldoms in their own right; such as the only daughter and child of the 4th Earl of Salisbury, Lady Alice Montacute, suo jure 5th Countess of Salisbury (great-great-grandmother to Queen Katherine Parr). So Anne descended from the 7 Earls of Ormonde, but they go back to Edward I at the highest. Even Katherine Parr descends from the 1st Earl of Ormonde via his daughter Lady Petronilla Butler, Lady Talbot [and that’s from Maud Green’s ancestry]. The title Earl of Ormonde was actually forfeited in 1513 [the 7th Earl] and Earl of Wiltshire in 1460.[1] The wife of the 7th Earl, Anne Hankford, was the granddaughter of Sir John, 3rd Earl of Salisbury who descended from Edward I, but Katherine Parr descended from the 5th Countess of Salisbury, Lady Alice Montacute and her husband Sir Richard Neville, who by right of his wife became the 5th Earl of Salisbury.

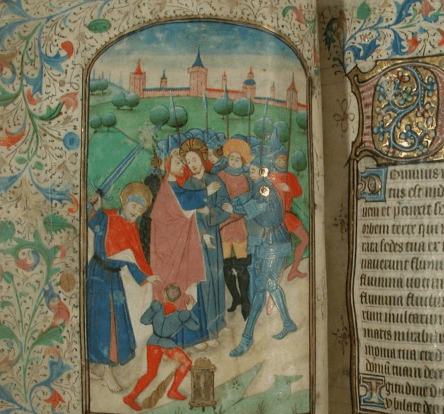

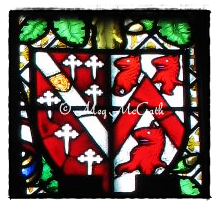

![Anne Bullen, daughter of Thomas, Earl of Wiltshire [Stained Glass from Hampton Court]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/a-boleyn-4-1.png?w=584)

Anne Bullen, daughter of Thomas, Earl of Wiltshire [Stained Glass from Hampton Court]

I’m also finding that she WAS known as Bullen, but at some point, the name was changed to Boleyn. The Parr family did that I think — but just dropped the “E”; their surname has been written as such; Parre. Bullen and Boleyn are completely different.

Queen Jane Seymour, wife no. 3.

Jane Seymour descended from Edward III, but her paternal lineage is lacking in “royal” or “nobles”. Like the Boleyns, the Seymour family couldn’t trace their paternal lineage much further than a few generations; John Seymour was the first Seymour to pop up (b. 1400). The paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Darrell’s lineage (through her mother), had some interesting connections back to several illegitimate children; one from King John and a few from Henry I of England. It’s the maternal lineage that gave Jane her “royal” connection to Edward III by the wife of Sir Philip Wentworth (maternal great-grandmother of Queen Jane). Hon. Mary Clifford gave Queen Jane descent from the 1st Baron Neville of Raby Castle, William Montacute 1st Earl of Salisbury, Lady Elizabeth suo jure 4th Countess of Ulster (wife of Lionel of Antwerp and mother to Philippa of Clarence). The Countess of Ulster descended from Joan of Acre (daughter of Edward I) and Lady Maud of Lancaster, daughter of Henry 3rd Earl of Lancaster (nephew of Edward I of England). Lancaster’s other daughter, Lady Mary of Lancaster was an ancestor to Clifford. Clifford also descended from several illegitimate children by John I and Henry I of England.

Queen Katherine Howard, wife no. 5.

As for Katherine Howard, she had the same ancestry as Anne Boleyn through her father Lord Edmund Howard. Her paternal lineage was “more noble” and of “better birth”. Looking at Howard’s mother (Jocasa Culpepper) however, she was of common stock. But Lady Howard did happen to descend from King Edward I by her maternal grandmother, Elizabeth of Groby Ferrers. By her, Lady Howard was a descendant of Princess Joan of Acre (second surviving daughter of Edward I by his first wife) and her first husband Sir Robert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester. Elizabeth of Groby Ferrer’s mother, Philippa Clifford was a descendant of Hon. Maud Fiennes, wife to Lord Mortimer of Wigmore — she had the amazing pedigree that went back to Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine’s daughter, Queen Eleanor of Castile. Philippa Clifford also descended from several illegitimate children of the early “Plantagenet” kings; twice by John I and several of Henry I of England. She even descended from David I of Scotland a few times. By this lineage Lady Howard also descended from Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March and Joan Geneville.

Queen Katherine Parr, wife no. 6.

So who were Katherine Parr’s great-grandparents? Some of the most important figures in history! A baron or Lord who was Sheriff of Northamptonshire among other high offices, an heiress of a prominent knight, a Baron, a daughter of an Earl (uncle to the Kings of England) and suo jure Countess (both of royal blood), a Lord/Baron, a daughter of a knight, a prominent knight (among other positions), and a daughter of an aunt to the royal family.

Sir Thomas Parr, Lord Parr of Kendal’s mother was the niece of Sir Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, also known as “Warwick, the Kingmaker,” one of ”the” most important figures in the War of the Roses. Parr was also a great-grandniece, however many times removed of King Richard II as they shared the same mother/grandmother, Princess Joan of Kent, suo jure Countess of Kent, Baroness Wake of Liddell, and Princess of Wales. Katherine was just about related to every noble and royal at court who came before or during her time; Edward IV and Richard III were first cousins, thrice removed of Katherine Parr. Their wives, Anne Neville and Elizabeth Woodville, were also a first cousins, twice removed. In fact, husband two, Lord Latimer, and three, King Henry, were within the “forbidden” fourth degree of consanguinity as 3rd cousins.

Katherine Parr’s family has a pretty “noble” back round and her family was actually high up in the court scene [at this time, my recorded research of Parr’s at court traces back to Sir William Parr (c.1356-1405), a close confidant of Henry IV of England]. We just don’t see this because Parr is always seen as this “nobody who came from nowhere” when in actuality she was the daughter of a substantial knight [just like Thomas Boleyn would become].[4] Starkey even quotes, “like the family of King Henry’s second wife, the Boleyns, the Parr family had gone up in the world as a result of royal favor and successful marriages.”[4]

The “lowly” marriage of Mary Boleyn to Sir William Stafford — unlike “The Tudors” insistence that he was a “nothing” — Stafford was actually the grandson of Sir John Fogge and Alice Haute (cousin to Queen Elizabeth Woodville). This connection made Stafford a cousin to Parr’s mother, Maud Green (her aunt was Stafford’s mother, Margaret).

The notion that Anne Boleyn and Katherine Parr were not on equal ground at birth is ridiculous. Katherine was of even “higher birth” than Anne. In fact, Sir Thomas Boleyn and Sir Thomas Parr [Lord Parr of Kendal according to Bernard Burke and other sources] shared the same circle around Henry VIII and were knighted at the same time [1509]. If not for his early death in 1517, he would have been given the title settled upon his brother or that of which he was heir or co-heir to, i.e. Lord FitzHugh of Ravensworth, which to this day, FitzHugh and the others, are still in abeyance between his daughter’s descendants [the Earls of Pembroke] and that of his aunt, Alice, Lady Fiennes. We all know that those in favor, especially relatives of the King’s wives were favored, and if not for Henry’s want and need to marry Anne, her father and brother would not have been elevated so high; and she would not have been created Marquess/Marchioness of Pembroke. We clearly see this with the Parr family as well. Parr’s brother (created Baron Parr of Kendal and Earl of Essex), uncle (1st Baron Parr of Horton), brother-in-law (Lord Herbert), and other family members were also elevated when Henry married Katherine.

Fact: Katherine Parr descends from Edward I of England more than any other wife, including Anne Boleyn. It would be nice if the quote was changed and perhaps the sentences from Agnes Strickland and David Starkey could be put in. It is not entirely fair to Katherine Parr and it would be nice if for once we took a look at her family’s history which if you look at it — it’s full of nobility and royalty.

More info: Ancestral Lineage of Queen Katherine Parr

DISCLAIMER:

This is not a blatant attempt to attack or trash any queen. This has been an on going issue on Wikipedia to which people refuse to look at — therefore a blog is being written. This genealogy blog was done due to editors on Wikipedia who keep inserting that “Anne was of more noble blood than the other English wives.” The blog is simply to show that both women were born on equal grounds, BOTH daughters of courtiers who were knighted at the SAME time in 1509. Katherine’s father, however, died in 1517 — preventing any further advancement which Thomas Boleyn enjoyed later on. The lineage of the Parrs’, however, simply shows that Katherine’s ancestral lineage was better and more established at court. I chose to compare these two because it is obvious with Jane Seymour that her pedigree, even though it includes Edward III, is pretty far removed from the nobility and royalty at court when she became queen. As for Katherine Howard, one could argue that she was just as noble or more than Anne and Katherine as her father was the son of the Duke of Norfolk and thus styled “Lord”. The Howard’s were somewhat “removed” by the time Katherine Howard became queen though, but had been previously close to the crown. Howard’s female side, the Culpepers’, was however much like Jane Seymour’s lineage. The boost of lineage for the Boleyns’ is probably due to the fact that Anne caused much controversy on the way to becoming queen. Parr is often overshadowed due to not having any surviving children among other factors. Anne of course, was the mother of Queen Elizabeth I, who is known today as “Gloriana”.

References:

- John Debrett. “Debrett’s Peerage of England, Scotland, and Ireland,” [Another], Volume 2. 1825.

- Paul Murray Kendall. “Richard The Third,” pp. 193-6, 365.

- Douglas Richardson. “Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study In Colonial And Medieval Families,” 2nd edition, 2011. pg 273-78.

- David Starkey. “Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII,” Chapter: Catherine Parr, HarperCollins, May 4, 2004.

- Christopher Wordsworth. “Ecclesiastical biography or, Lives of eminent men, connected with the history of religion in England: from the commencement of the Reformation to the Revolution,” 3d edition, London: J.G. & F. Rivington, 1839.

- Sylwia S. Zupanec. “The daring truth about Anne Boleyn: cutting through the myth,” 8 November 2012.

- Crofts Peerage, Ormonde, Earl of (I, 1328-dormant 1997)

- Charles Ross. “Edward IV,” (second ed.) New Haven: Yale University Press. 1997.

- David Starkey. “Holbein’s Irish Sitter?,” The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 123, No. 938 (May, 1981), pp. 300-301+303.

- Sidney Lee. Dictionary of national biography, Volume XXVIII: From HOWARD to INGLETHORP, Macmillan, Smith, Elder & Co. in New York, London, 1891. pg 64-67.

- Sidney Lee. Dictionary of national biography, Volume XXVIII: From HOWARD to INGLETHORP, Macmillan, Smith, Elder & Co. in New York, London, 1891. pg 1.

![Katherine Parr and Anne Boleyn, both were of equal birth -- Katherine's lineage, especially that of her father however, was better and more established at court than the Boleyn's. [David Starkey]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/kat_anne.png?w=584)

![Sir James Butler, 9th Earl of Ormonde, son and heir of Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormonde [the rightful heir to the Earldom]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/butler-earl-of-ormonde.jpg?w=584)

![Anne Bullen, daughter of Thomas, Earl of Wiltshire [Stained Glass from Hampton Court]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/a-boleyn-4-1.png?w=584)

![Tomb of Queen Katherine at Sudeley features the her family arms impaled with that of her four husbands [Latimer & Parr]. Copyright Meg McGath](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/latimer-lady.png?w=584)

![Wyke Manor in Wick, Worcestershire. [Wikipedia]](https://tudorqueen6.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/wick_manor.jpg?w=584)