The Vultures are circling as Henry lies on his death bed. He is surrounded by his son, Edward, as the king prepares him to become the next Tudor king.

In 1544, it was apparent that Queen Katherine Parr had been acquainted with the terms of King Henry VIII’s will for it named Katherine regent for the young Prince Edward if he were to die while in France. The fact that Katherine had been named possible regent in the event of the sudden death of the king makes one wonder what the will of King Henry looked like when he died on 28 January 1547. For three days after the King’s death, the council convened while the outside world was unaware of what had happened. Even Henry’s other children were not told. This extremely disturbed the Lady Mary who at one time had been named Princess and heiress to her father’s throne.

After the death of King Henry, Mary was not told of his death for several days. Edward’s minority council took elaborate precautions to ensure all was in place before they made an official announcement. This action made Mary extremely angry, but she could do nothing about it. Yet how ever wary Edward’s councillors were, nothing could alter the fact that Mary was in her own right heiress to the throne. For the time being, Mary would stay with the now Dowager Queen, Katherine, who was again for the third time, a widow. At the time of her father’s death Mary was aged 31. Mary’s reaction to her father’s death was never recorded as she never publicly mourned his death. She was apparently more irritated at the fact that no one had told her that her father had died until days later. Most likely her reaction to the news was mixed grief and some kind of relief.

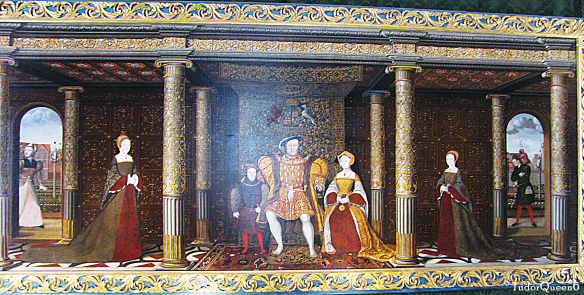

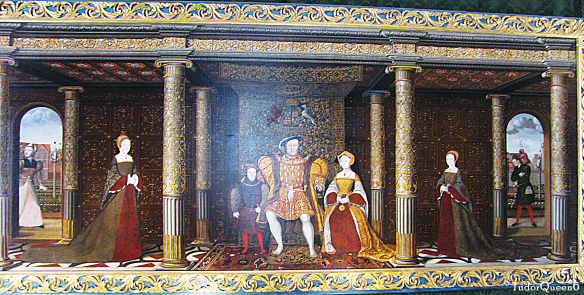

The “Succession Portrait”, c. 1544, artist, after Holbein.

Hampton Court Palace. The portrait which was done while Katherine Parr was queen, features Prince Edward’s mother, Queen Jane Seymour. © TudorQueen6

As for the Will of Henry VIII, it is quite possible that during those three days the men of the council were convening on how to alter the will to exclude the now Queen Dowager from any further power or influence over the boy King Edward. These conspiracy theories have been examined within Susan James’s biography on Queen Katherine. One theory is that Henry’s will was originally set up to pass the kingdom to his heir and that the regency council was to be led by the Earl of Hertford. Another version has Sir Anthony Denny, Sir William Paget, and Sir William Herbert (the Queen’s brother-in-law) rigging the whole will to give the Earl full control and some even go as far to name them as the masterminds of the fall of Gardiner and the execution of the Earl of Surrey. This theory of course can be refuted as the king was in control of his kingdom up until the last few hours of his life.

Although the king’s abilities had been diminished it is true that Sir Anthony Denny and Sir William Paget had control of those who accessed the privy chamber but not against the king’s will. In December 1546, the Privy Council meetings no longer took place at Westminster and were now being held at Hertford’s Somerset House. So if the queen had been summoned to the king at some point, the command would have been obeyed, but it is not for certain if the queen gave a command to see him that it would have been honored. It is not even sure whether or not the king would have been informed if she had demanded to see him.

King Edward VI, c.1550, attributed to William Scrots. Hampton Court Palace. artist, after Holbein. Hampton Court Palace. © TudorQueen6.

Another theory to support that the will had been tampered with is the final will that was produced did not have a signature, but was stamped and was registered a month later. So in that is a possibility that the will had been changed in support of the Earl of Hertford’s wishes. It seems obvious to readers that the men of the council, including Hertford, didn’t want to be dependent upon a woman’s approval. The actions of King Henry and his mission to produce a male heir instead of depending upon his only daughter from his first marriage shows that men were still not willing to depend upon or even accept a woman governor of the realm. I tend to find this odd seeing how in other countries, including that of their neighbor Scotland, consorts had been given the position of Regent. In fact, Henry’s sister Margaret, for a time had been Regent in Scotland and even Henry’s first wife, Katherine of Aragon acted as Regent for a longer period then Queen Katherine Parr had. Still, the feeling of having a woman in a position of power was not accepted and in some cases like Katherine of Aragon’s sister, Juana I of Castile, they were driven out by other men. Juana was driven out by the men in her life; her husband, father, and eventually her son who took over as the Holy Roman Emperor.

It is also thought that perhaps Katherine’s moral sense might have been an impediment as to the acquisition of Crown lands to which the council helped themselves to after they had been established. Henry’s second wife and queen, Anne Boleyn, had at one time felt the same way during the dissolution of the monasteries. Her opinions and interactions that condemned the way the properties and money were being dispersed had some doing in her downfall. Katherine completely disapproved of the way the lands were dispersed and her opinion was recorded as such. In 1549, Sir Robert Trywhitt testified that Katherine had said, “Mr. Trywhit, you will see the king, when he cometh to his full age, he will call his lands again, as fast as they be now given from him.”

“The enraged presence of a mother defending her son’s inheritance from the depredations of his omnivorous council would have been the last thing the lord protector or the council wanted.”

Yet despite all of this, the one responsible may in fact have been King Henry himself. Henry’s opinion of having women rule was and is more then obvious due to his split with Katherine of Aragon and marriage to Anne Boleyn. Henry did not believe that a woman could rule alone. It was one thing to use Katherine as an unofficial councillor during her lifetime, but to leave her to run the kingdom while his son was a minor was a completely different thing. He didn’t want a wife to tell him what to do in pretty much anything so it is understandable as to why he sent Katherine away at the end of his life. He obviously didn’t want to deal with her suggestions on how to dispose of his crown. That he did not inform Katherine of his decision left her to suppose in a way that she was to be head of the regency council upon his death. Henry left Katherine this bitter gift after all that she had done as queen, including enduring his constant immortalizing of his “true wife”, Jane Seymour. He did this not only in his painting of the royal family but in his request to be buried next to her upon his death.

The fact that Henry sent all the women in his life away a month before his death may have also influenced him in his final decisions. In not having them around he wouldn’t have been prone to lamentations and fuss made by the women who might have been brought in to be included in the rule of the kingdom after his death. James states that Katherine’s preference to be near Henry during the last month of his life may have partly been due to her political motivations. She was very protective of the royal children and that was adamant from day one.

In the early hours of the 28th of January, King Henry VIII died. For three days court continued on schedule. Even the royal dishes were escorted into the King’s chambers accompanied by the sounds of trumpets to make it look like the King was still alive. During this time, the top members to be part of the council lobbied and devised for position and the final settlement. Sir William Paget was the last to hear the devised plan from the king himself. Within the three days it would come to pass that the Earl of Hertford would make himself Duke of Somerset and appoint himself as Lord Protector of the Realm which had not been Henry’s wishes according to his will or any other knowledge of those apparent.

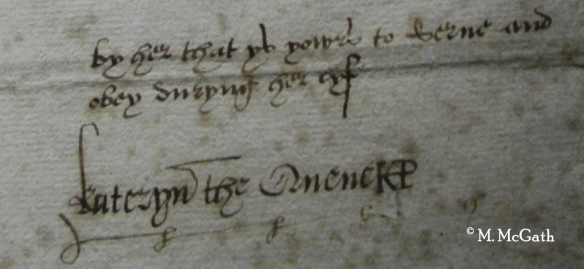

Katherine’s signature as Queen Regent. (Cotton MSS Vesp. F III fol. 16. b)

The position of power and the door to the regency council was shut in the Queen Dowager’s face and once again, Katherine was left to mourn a dead husband. Despite the outcome of the situation, a piece of history may provide proof that she was to be head of the regent council as shortly after Henry’s death, Katherine signed two documents as “Kateryn the Quene-Regent, KP.”

Sources:

- Susan James. Catherine Parr: Henry VIII’s Last Love, The History Press, US Edition, 2009. pg 356-59.

- Linda Porter. The Myth of “Bloody Mary”: A Biography of Queen Mary I of England, St. Martin Griffins, 2010.

- Anna Whitelock. Mary Tudor: England’s First Queen, Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2009.

© 28 January 2012

Meg McGath